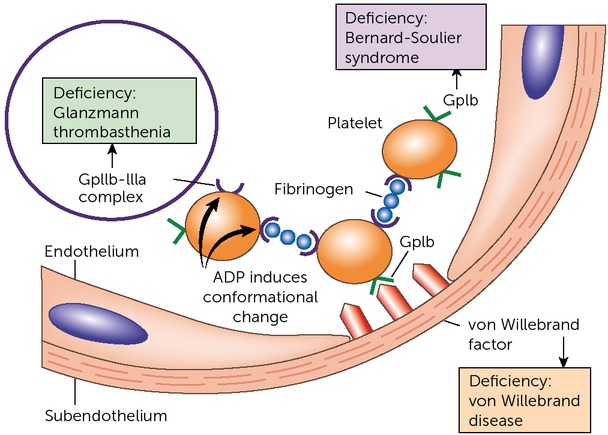

Platelets are an essential part of primary haemostasis. After damage to the vessel wall, platelets adhere to it via von Willebrand factor. The activated platelets then aggregate, a process mediated mainly by fibrinogen, which binds the platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa) complex on platelets, ultimately forming the platelet plug. Glanzmann’s disease is a very rare inherited platelet function disorder, caused by quantitative or qualitative defects of the GPIIb-IIIa complex, leading to impaired formation of the platelet plug (Figure 1). Without the platelet plug, it becomes more difficult for the clotting factors to create a stable fibrin clot.

Figure 1

Glanzmann’s disease is caused by a deficiency of the platelet GPIIb/IIIa complex (figure adapted from Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins Basic Pathology, 9th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012 [9])

Glanzmann’s disease is a severe bleeding disorder, with bleeding symptoms including easy bruising, epistaxis, menorrhagia, post-partum haemorrhage and bleeding of the gums. Less common symptoms are gastrointestinal bleeding, haematuria, and bleeds in joints or muscles and the central nervous system. Treatment, according to national guidelines, comprises platelet transfusion, recombinant FVIIa and tranexamic acid. Platelet transfusion may result in HLA immunisation, which limits transfusion efficacy. It is estimated that one in 1,000,000 individuals have Glanzmann’s disease, (although the exact number is unknown), with a slight predominance in women compared to men [1].

Case presentation

An 86-year-old woman presented at the emergency department with chest pain, tiredness and shortness of breath. These complaints had worsened over the previous two weeks. The patient had originally been diagnosed with von Willebrand disease, which was changed to Glanzmann’s disease in 1973 after an endometrial curettage for menorrhagia was complicated by a perforation and severe bleeding. In 2007 and 2008, the patient suffered from several episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding due to angiodysplasia and was treated with endoscopic coagulation, recombinant coagulation factor VIIa (rFVIIa) and HLA-matched platelet transfusions. In 2011, the patient was given rFVIIa after a head trauma. Her medication included prophylactic tranexamic acid and treatment for hypothyroidism. There was no medical or family history of cardiovascular or pulmonary disease. After the loss of her husband, the patient became socially isolated and suffered from depression. She no longer spoke with her only child.

Further examination ruled out cardiac or pulmonary causes for the patient’s complaints. Vital signs were normal. Laboratory investigation revealed anaemia (haemoglobin 5.0 mmol/L or 8 g/dL, reference value 12-15.2 g/dL) and iron deficiency (blood iron 3.6 μmol/L, reference value 10-30 μmol/L).

Management and outcome

The patient was admitted in the hospital to correct her anaemia and iron deficiency. She was treated with repeated blood transfusions, FVIIa infusions and tranexamic acid. Unfortunately, the anaemia failed to resolve. Abdominal imaging did not show intra-abdominal bleeding. Even though the patient did not report rectal bleeding or melena, a gastroscopy and colonoscopy were performed, neither of which revealed a clear bleeding focus. Taking the patient history into account, and as other causes for the anaemia had been ruled out, a capsular endoscopy was performed. This showed fresh blood in the jejunum. We therefore concluded that the anaemia was caused by angiodysplasia in the gastrointestinal tract.

Angiodysplasia is the most common vascular lesion of the gastrointestinal tract. A degenerative lesion of previously healthy blood vessels, it is found most commonly in the cecum and proximal ascending colon [2, 3]. The vessel walls are thin, with little or no smooth muscle, known as thin vessel malformation. Confusion about the exact nature of these lesions has resulted in them being referred to by a multitude of terms, including arteriovenous malformation, haemangioma, telangiectasia and vascular ectasia. These terms have varying pathophysiologies, with a common presentation of GI bleeding. Angiodysplasia is usually diagnosed by endoscopy, but can only be seen when there is active bleeding [3]. Treatment usually consists of endoscopic coagulation, but often systemic therapy is necessary. Up to half of all angiodysplasias resolve spontaneously [3]. The severity of bleeding from angiodysplasia ranges from asymptomatic to transfusion-refractory anaemia.

In light of reports showing the cholesterol-independent vascular effects of statins on angiogenesis, atorvastatin 80mg each day was prescribed for three months [4]. After two months, side-effects, including nausea, muscle pain and hair loss, led to discontinuation of the atorvastatin. Regrettably, the patient was still dependent on two-weekly blood transfusions to keep her haemoglobin at an acceptable level. We therefore started treatment with thalidomide 50mg for six weeks, followed by 100mg for six weeks.

In the late 1950s, thalidomide was promoted as a ‘wonder drug’ to treat a range of conditions, including headaches, insomnia and depression. It was popular because it was atoxic and it was therefore deemed impossible to overdose on it. However, long-term use led to irreversible peripheral neuritis in many patients. It was then remarketed as a short-term treatment for pregnant women, typically in the first three months of pregnancy, to combat morning sickness. Throughout the world, about 10,000 cases of infants with phocomelia (malformation of the limbs) due to thalidomide were reported. Nowadays, thalidomide is used in the treatment of a number of conditions, including erythema nodosum leprosum, multiple myeloma and various other cancers, as a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. The main side-effects attributable to thalidomide are fatigue, constipation and peripheral neuropathy, which were also present in our patient.

After 12 weeks of treatment, thalidomide was stopped due to side-effects, even though regular blood transfusions were still necessary. However, after discontinuation of treatment, the gastrointestinal bleeding miraculously ceased. During an eight-month period, the patient received 117 red blood cell transfusions, 6 platelet transfusions and 14 injections of 7mg rFVIIa infusions.

Table 1

Treatment according to the Dutch guidelines [5]:

During this period, the patient suffered considerably and lived between hope and fear. The impact of the psychosocial burden was high. At first, she was not willing to accept any help from a home care institution or support from her general practitioner. However, at our explicit request, she eventually agreed to receive a degree of support and guidance from our social worker and her general practitioner. After careful consideration and in consultation with the Haemophilia Treatment Centre, she opted to have a ‘do not resuscitate’ policy and to stop the thalidomide due to the side-effects. At this time, her haemoglobin normalised.

Discussion

In some cases, it is necessary to deal with numerous issues and, therefore, many different specialists – but it is essential to maintain a balance. It is sometimes necessary to take a step back and reflect on the proposed line of treatment: Is it still working? Can the patient deal with the side-effects? Can she hold up? We must respect the patient’s autonomy over treatment and management, and work together as a team. Medical care can be very difficult. Some cases seem to be untreatable. Patients are becoming more assertive and need to have a say in the decision-making around treatment options and choice of medication. Communication and cooperation among the various specialists participating in the patient’s care is key to a successful outcome.

This case concerns a frail elderly patient with a poor social network, who was initially not willing to accept any help at all. However, at several points she became desperate, but found it difficult to make a decision as to what to do. Involving the general practitioner and social worker was one of our solutions. Often a compromise was made that was acceptable for both the patient and the haemophilia treatment team. For example, she did not want to accept home care or sit in a wheelchair, but agreed to have a 24-hour emergency button installed in her home, in case she had an accident. As a haemophilia treatment team, our tightrope walk was about trying to find a balance between interference and professional guidance.