Patients with haemophilia A (HA), especially in severe cases, suffer from frequent internal blood loss within the joints, resulting in abnormal deposition of iron in the synovium [1,2]. However, synovial iron deposits are not physiologically functional, since they are not readily available for the synthesis of haemoglobin; rather, they are pathological mediators of inflammation, resulting in crippling haemophilic arthropathy [2]. Frequent occult or overt external blood losses arising spontaneously or from accidental bodily injuries would be expected to deplete normal storage compartments, such as the liver and bone marrow, eventually leading to iron deficiency in patients suffering from HA. In fact, a previous study has shown that such blood losses were frequently associated with iron deficiency, even among haemophiliacs living in developed countries [3]. Moreover, a more recent study from Nigeria demonstrated that the risk of iron deficiency in haemophiliacs was higher among patients with severe haemophilia, because it is associated with more frequent spontaneous and accidental bleeding episodes [4].

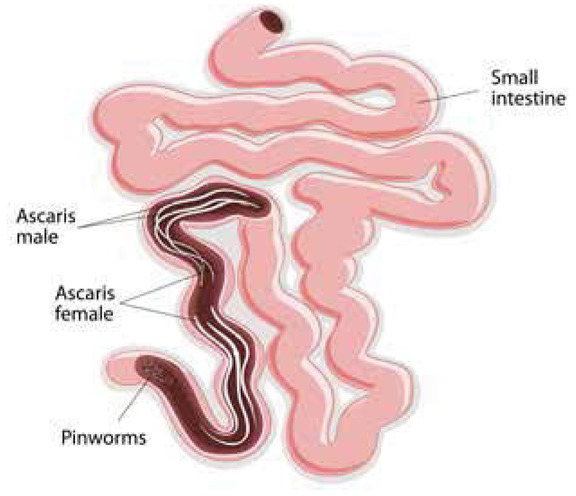

However, in developing tropical countries with poor sanitation, intestinal helminths are prevalent and have been shown to contribute to the high incidence of iron deficiency anaemia within the local populations [5, 6, 7]. Intestinal helminth infections are endemic in Nigeria, where the prevalence can be as high as 60%, especially among young children who are more vulnerable to infections than adults [7]. Previous studies have shown that intestinal helminths cause or aggravate anaemia in various parts of the Nigerian population, ranging from patients with background immunosuppressive diseases, such as sickle cell disease and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, to apparently healthy children and adults, including prospective blood donors [7, 8, 9, 10]. Intestinal helminths cause iron deficiency by inducing chronic malabsorption and gastrointestinal haemorrhage, even in haemostatically normal persons [5,7].

We believe that the haemostatic abnormality associated with haemophilia would create a pro-haemorrhagic host-parasite relationship, making haemophiliacs particularly vulnerable to the haemorrhagic effects of intestinal helminths. This potentially significant vulnerability has never been investigated, as most publications on haemophilia have come from developed nations where parasitic diseases are not prevalent – hence the justification for this study. We predict that intestinal helminth infections will increase the risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency among haemophiliacs living in tropical countries such as Nigeria. If our prediction is correct, the frequency and the relative risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency will be higher among haemophiliacs infected by intestinal helminths in comparison with their uninfected counterparts. To test our prediction, we retrospectively evaluated the frequency of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency in haemophiliacs with and without intestinal helminths, and assessed their relative as seen at the time of diagnosis in hospitals in northern Nigeria.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective study of data accrued from patients who were consecutively diagnosed with HA during a cumulative period of 32 years at different time periods in five northern Nigerian tertiary hospitals, including the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri, North East Nigeria (1996-2007); the State Specialist Hospital, Maiduguri, North East Nigeria (19962007); Murtala Muhammad Specialist Hospital, Kano, North West Nigeria (2008-2010); Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano, North West Nigeria (2007-2009); and Reshidi Shekoni Specialist Hospital, Dutse, North West Nigeria (2011-2012). The data collected from the five hospitals were collated and subjected to statistical analysis. Haemophilia patients’ parents or guardians are routinely asked for voluntary consents for future research use of data accrued at the point of diagnosis or any emergency visit at the hospitals. The study was conducted with the approval of local institutional ethics committees and with informed consent obtained from parents or guardians of patients.

Patient selection criteria

Patients who presented with bleeding diathesis and were diagnosed with HA at the five centres during the period under review were included in this study. All patients studied in this report were treatment and transfusion naïve, thus excluding the impact of blood transfusion on ferritin levels. None of the patients had liver disease or any acquired bleeding disorder.

Data retrieval

Relevant data were retrospectively retrieved from patients’ medical and laboratory records as documented at the time of diagnosis. The data included demographic profile (age and sex), haemoglobin (Hb) concentration and mean corpuscular volume (MCV), FVIII levels, frequency of intestinal helminths as determined by stool analyses, frequency of gastrointestinal haemorrhage as determined by clinical history, and frequency of iron deficiency as determined by serum ferritin analyses. The data were collated and statistically analysed.

Diagnosis of HA, determination of FVIII levels and disease severity

Diagnoses of HA were made based on clotting profiles that revealed normal platelet count, bleeding time, prothrombin time and thrombin time, with prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) corrected by mixing with fresh normal plasma but not with aged plasma or serum [11]. FVIII assays were performed by automated coagulometers or manual techniques, based on the ability of serial dilutions of patients’ plasma and standard plasma to correct the prolonged APTT of plasma known to be severely deficient in FVIII. Patients were categorised as severe (FVIII level <1%), moderate (FVIII level 1-5%) or mild (FVIII level 6-40%) haemophiliacs [11].

Evaluation of serum ferritin levels and application of cut-off values for iron deficiency

Serum ferritin levels were determined by ELISA techniques using commercial enzyme immunoassay kits in accordance with manufacturer’s methodology, based on standard techniques [12]. The cut-off points for the diagnosis of iron deficiency in this study were serum ferritin levels <12μg/L for patients younger than 5 years and <15μg/L for patients older than 5 years, as published in standard W.H.O. guidelines [13].

Stool analysis for intestinal helminths

Stool analysis is routine for anaemic patients in Nigeria to detect background endemic helminthic infections. Patients’ stool samples were investigated in the hospitals’ microbiology laboratories using a standard formal ether concentration technique, with stool sediments examined microscopically for identification of parasites, segments, ova or larvae. The severity of intestinal helminth infections were expressed as mild, moderate or heavy, based on the number of eggs per gram of stool, based on standard criteria [14,15].

Retrospective analysis of past history of gastrointestinal haemorrhage

The medical case notes of each patient were scrutinised to determine the number of patients with a past history of one or more episodes of acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the form of haematemesis, haematochezia or melena, as documented during clinical history evaluation at the time of diagnosis.

In this study, haematemesis referred to any episode of vomiting of bright red blood, which is generally associated with the upper gastrointestinal tract; haematochezia referred to any episode of passage of reddish blood-stained stool, which is commonly associated with lower gastrointestinal bleeding; and melena referred to any episode of passage of tarry black stool, which is usually due to bleeding in the upper gastrointestinal tract wherein the normal red colour of blood is altered by the gut flora to the tarry black colour. Black stool was considered as melena only after excluding a recent history of ingestion of iron containing haematinics, which may also cause blackish discoloration of stool in the absence of gastrointestinal haemorrhage [16,17].

Statistical analysis

Values of studied parameters were compared between haemophiliacs with and without intestinal helminths, using the t-test for mean values and the χ2-test for proportions, with p-values of less than 0.05 taken as significant. The relative risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency among haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths was determined by Poisson regression analysis. Value of relative risk (RR) was considered statistically significant if the lower limit of 95% confidence interval range (CI95%) was greater than 1.0, with a p-value of less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 19.0).

Results

The data of a total of 42 male haemophilia patients were retrospectively evaluated, 15 (35.7%) of whom were infected with intestinal helminths. Three type of intestinal helminth were found in this study, including Ancylostoma duodenale, Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura; their frequency distribution among the 15 infected haemophiliacs are shown in Table 1. All 15 haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths had moderate infections.

Table 1

Frequency distribution of parasites among 15 haemophiliacs infected with intestinal helminths

The type, frequency and pattern of gastrointestinal haemorrhages, which included haematemesis, haematochezia and melena as documented in the clinical records of haemophiliacs with and without intestinal helminths infections, are shown on Table 2. This shows that haematochezia and melena were the predominant types of gastrointestinal haemorrhages in our patients.

Table 2

Type, frequency and pattern of gastrointestinal haemorrhage among haemophiliacs with and without intestinal helminth infections

A comparative analysis of the mean age, Hb concentration, MCV, severity of haemophilia, frequency of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency between haemophiliacs with and without intestinal helminths is shown in Table 3. There were no statistically significant differences in mean age and proportions of severe and non-severe haemophilia between patients with and without intestinal helminths. However, haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths had significantly higher frequencies of gastrointestinal haemorrhage (73.3% vs. 18.5%, p<0.05) and iron deficiency (60% vs. 22.2%, p<0.05), as well as lower mean values of Hb concentration (6.9g/dl vs. 9.2g/dl, p<0.05) and MCV (76fl vs. 87fl, p<0.05), in comparison with haemophiliacs without intestinal helminths. By regression analysis adjusting for age and severity of haemophilia as confounding variables, haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths had elevated an relative risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage (RR=3.4, CI95%: 2.4- 4.3, p=0.007) and iron deficiency (RR=2.5, CI95%: 1.7-3.3, p=0.009).

Table 3

Mean age, Hb concentration, MCV, frequency of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency among haemophiliacs with and without intestinal helminth infections

Discussion

The actual prevalence and incidence of haemophilia in Nigeria has not yet been determined. However, Nigeria has the largest population in Africa, yet the patient data captured in this study is relatively small, despite multicentre collation within a fairly extended cumulative time period. This is attributable to the high mortality associated with haemophilia in low-resource tropical countries such as Nigeria. Clinical care for haemophiliacs in the tropics is often inadequate and is characterised by poor access to healthcare facilities due to ignorance, poverty and logistical difficulties, coupled with a high patient attrition rate. Consequently, routine clinical follow-up is usually very irregular. Hospital-based researchers must therefore often work with relatively sparse retrospective data collected at the time of diagnosis or during bleeding emergencies.

Nonetheless, this study revealed that around one third of haemophiliacs were infected with intestinal helminths. The type and frequency of the intestinal helminths seen in this report depict a familiar spectrum of common soil-transmitted helminths that are endemic and ubiquitous within the local population, as revealed by previous studies conducted among various subject groups in Nigeria [7, 8, 9, 10].

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage is not an uncommon clinical problem in haemophiliacs, in whom it may occur spontaneously or due to factors such as duodenal ulcers, gastritis, Mallory-Weiss syndrome and portal hypertension with oesophageal varices, as reported in studies from non-tropical and developed countries [16,18]. Since most reports on haemophilic gastrointestinal haemorrhage originate from non-tropical countries, intestinal helminths have never been documented as aetiologically relevant factors for gastrointestinal haemorrhage in haemophiliacs. However, the results of this study show that, in comparison with counterparts without intestinal helminths, haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths have a higher frequency of gastrointestinal haemorrhage, with a relative risk of 3.4, implying that haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths are around 3.4 times more likely to experience gastrointestinal haemorrhage than those without. This finding confirmed our prediction that intestinal helminth infections increase the risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage in patients with haemophilia. Consequently, haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths had lower Hb and MCV values and a correspondingly higher frequency of iron deficiency, with a relative risk of 2.5, compared to those without. This implies that haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths are 2.5 times more likely to have an iron deficiency than those without.

We believe that the increase in frequency and relative risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency among haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths is due to a pro-haemorrhagic host-parasite relationship, initiated by parasite-induced mucosal injuries perpetuated by the host’s haemostatic abnormality. The intensity of morbidities associated with intestinal helminths, such as gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency, is reported to be directly related to worm burden, as assessed by the severity of infection [15]. Therefore, while mild infections may cause few or no morbidities, moderate to severe infections would be expected to cause significant clinical problems [15]. Although all helminth infections found in this study were of moderate severity, it should be appreciated that because of their background haemostatic abnormality, haemophiliacs with intestinal helminths will experience a disproportionately higher risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency than would be expected for the actual parasite burden and severity of infection.

All three soil-transmitted helminths found in this study are known to induce gastrointestinal mucosal injuries, recurrent or chronic gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency, even in haemostatically normal persons [15]. Thus, even in haemostatically normal hosts, the hook worm is reported to induce a wide spectrum of gastrointestinal haemorrhages, ranging from occult blood loss to melena and frank haematochezia, all of which are associated with iron deficiency [19, 20, 21, 22]. Moreover, Ascaris lumbricoides has been associated with haematochezia, haematemesis and iron deficiency, even in haemostatically normal hosts [23, 24, 25]. Similarly, Trichuris trichiura is capable of inducing both occult and frank gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the form of haematochezia, as well as iron deficiency, even in haemostatically normal hosts [26, 27, 28]. We therefore believe that the haemostatic abnormality of the haemophilic host creates a pro-haemorrhagic host-parasite relationship, increasing the risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency in haemophiliacs infected by these intestinal helminths.

We deduced that haemophilic hosts infected by Ascaris lumbricoides and Trichuris trichiura parasites have a high risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage due to a pro-haemorrhagic host-parasite relationship resulting solely from the host’s intrinsic haemostatic abnormality. However, we believe the host-parasite relationship between the Ancylostoma duodenale parasite and the haemophilic host would be more pro-haemorrhagic as a result of a dual concert between the haemostatic abnormality of the host and anticoagulants produced by the parasite. Ancylostoma duodenale is known to manipulate host haemostasis by producing anti-FXa and anti-FXIa anticoagulants, which would synergistically interact with the pre-existing haemostatic abnormality of the haemophilic host – a situation that would lead to a greater risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage [29]. It can thus be surmised that the high frequency and risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency seen in haemophiliacs infected by intestinal helminths are due to highly pro-haemorrhagic host-parasite relationships, resulting from the host’s intrinsic haemostatic abnormality, coupled with concurrent manipulation of the host’s haemostatic system by anticoagulants produced by some of the parasites.

The findings of this study have shown that intestinal helminth infections are undesirable in haemophiliacs because of their special vulnerability to gastrointestinal haemorrhage, with its associated risk of iron deficiency. The potential adverse effect of iron deficiency in the haemophilic child goes beyond physical manifestations such as anaemia, growth retardation and exercise intolerance. In addition, it is associated with adverse cognitive and psychological effects, which can lead to attention deficit, social withdrawal and poor intellectual attainment in school-age children [30]. In order to curtail the high prevalence of iron deficiency and other morbidities associated with soil-transmitted helminths in poor nations, the WHO recommends periodic screening and de-worming programmes for all at-risk individuals, including children living in endemic areas [15]. Therefore, healthcare givers in the tropics should ensure that all haemophiliacs are regularly screened and de-wormed on the basis of existing WHO recommendations [15].

Conclusion

Intestinal helminth infections are associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal haemorrhage andiron deficiency in haemophiliacs. This is thought to be due to a pro-haemorrhagic host-parasite relationship, resulting from the host’s haemostatic abnormality, coupled with concurrent manipulation of the host haemostatic system by anticoagulants produced by some of the parasites. Haemophiliacs living in tropical countries should be regularly screened and treated for intestinal helminths in order to mitigate the risks of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and iron deficiency and their potentially adverse consequences, including cognitive retardation in the haemophilic child.