When Segawa Wasswa suffered a painful knee bleed in 2013 at the age of 12, he was taken to a rehabilitation care unit for children with bone disabilities. The doctors at the centre diagnosed him with a bone disease and operated on his knee. After his surgery, Waswa’s condition continued to worsen. Unsure of how best to treat him, his doctors transferred his to Mulago Hospital in Kampala, where he was tested and finally received a diagnosis of severe hemophilia A. Over time it became clear that his brother and two uncles had all died from complications related to haemophilia but none had ever received a diagnosis.

Waswa’s condition came to the attention of the Haemophilia Foundation of Uganda (HFU), which was able, through the WFH Humanitarian Program, to provide him with factor concentrates. Providing care to people like Waswa in Uganda has long been a challenge; many are untreated (Figure 1). It is a poor country that in recent decades has witnessed internal conflicts that have resulted in many casualties and displaced people. Inevitably, as the health care system struggles with communicable diseases, management of orphan diseases like haemophilia takes a backseat.

But the situation is changing and boys like Waswa are benefiting massively, thanks to the work of the HFU, a registered non-government organisation working to create positive change in the lives of Ugandans with bleeding disorders.

Health care and haemophilia in Uganda

According to the World Federation of Hemophilia annual global survey for 2014, there were just 80 confirmed diagnoses of haemophilia in Uganda [1]. This is clearly a massive underestimate that suggests many people are simply not coming to the notice of health care services.

The accepted incidence rate for haemophilia A is about 1 in 5,000 male births, and for haemophilia B is about 1 in 30,000 male births. In the United States, where there is good diagnosis and record keeping, the exact number of people living with haemophilia is not known although it is thought that about 400 babies are born with the condition each year [2]. A CDC study conducted in six states in 1994 estimated that about 17,000 people had hemophilia at that time. Currently, the number of people with haemophilia in the United States is estimated to be about 20,000, based on expected births and deaths since 1994.

Applying the accepted incidence and prevalence rates to Uganda, with its population of 35,918,915, would suggest that there should be around 1,940 people with haemophilia. The fact that so few are diagnosed reflects both the poor state of service development and the lack of patient awareness.

Uganda’s healthcare system

Mulago Hospital in Kampala is the largest state-owned hospital in Uganda, with around 1,500 beds, and sits at the top tier of Uganda’s complex healthcare system (Figure 2). This starts in the rural villages where village health teams staffed by volunteers advise patients and are able to refer them to level II health centres. These local health centres are located in most parishes and each will serve a few thousand people.

Level II facilities are supposed to be led by an enrolled nurse, working with a midwife, nursing assistants and a health assistant. They run outpatient clinics, treating common diseases like malaria and offering antenatal care. They also provide a referral service into the level III health centres, which are found in every sub-county in Uganda. These centres are said to have about 18 staff, who run a general outpatient clinic and a maternity ward: some even have a functioning laboratory. They refer into the level IV health centres, each of which serves a county or a parliamentary constituency and functions as a mini-hospital, with wards into which patients may be admitted. Each should have a senior medical officer and another doctor as well as a theatre for carrying out emergency operations (subject to water and power availability). Each district should also have a hospital that offers similar facilities to the level IV health centres along with specialised clinics and consultant physicians.

Some of these district hospitals also function as regional referral centres, able to refer patients on to Mulago Hospital, the national referral hospital. Despite this status, Mulago struggles to get by on a meager budget. Each year, the hospital requests 100 bn shillings ($3 bn) for its drugs budget, but gets only around one-tenth of that.

Uganda is a poor country where more than one-third of the population living on less than $1.25 a day. Health care expenditure accounts for 9.8% of the country’s gross domestic product, and in 2009 total health expenditure was $52 per capita [3]. Data for 2015 suggests life expectancy at birth is just 54.93 years and infant mortality rate is 59 deaths per 1,000 children [4].

Communicable diseases represent Uganda’s main burden of disease although there is also a growing burden from noncommunicable diseases such as mental health disorders. Neglected tropical diseases remain a big problem in the country affecting mainly rural communities. Furthermore, there are wide disparities in health status across the country, closely linked to underlying socio-economic, gender and geographical disparities. Segwa Waswa lives in a rural area of Uganda: now that he has a diagnosis and knows that treatment is available, the main problem facing him and his family is getting enough money to pay for transport to Mulago when he needs treatment.

Figure 2

A stamp printed in Uganda shows a health care worker taking an X-ray in Mulago Hospital, circa 1962. Picture credit: IgorGolovniov / Shutterstock.com

The distribution of healthcare facilities and funding in Uganda favours the nation’s cities (see panel above): 70% of physicians and 40% of nurses and midwives are based in urban areas, yet more than 80% of the population lives in the country’s rural areas, where poverty remains deep-rooted [5]. But alongside this government-funded system, there is a parallel network of private hospitals, and many doctors in the national system also work part-time at these private clinics to supplement their salaries.

HFU’s work in Uganda

HFU has taken an active role in developing the haemophilia service in Uganda. The work began by sourcing factor donations from generous organisations and distributing it to members who need it, at no cost. In addition, it lobbies government for support, and brings together patients living with haemophilia to share knowledge and to provide mutual support for those who face the considerable challenges that affect people with haemophilia in Uganda. After many years of lobbying, HFU has started to achieve successes. Today, it has a unit at the paediatrics ward at Mulago Referral Hospital in Kampala.

HFU is headed by chief executive Agnes Kisakye. In 2012, HFU joined the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH), and with guidance from Dr Kate Khair from the Haemophilia Centre at the Great Ormond Street (GOS) Hospital in London, Agnes set about assessing the provision of haemophilia care within the East African country, and the challenges faced by those with haemophilia. Throughout a lengthy programme of interview-based research, Agnes had one aim in mind – to enter a WFH twinning programme.

Her initial report highlighted the need to provide a comprehensive package for people with haemophilia in Uganda. Building on the availability of donated factor, she said this would require provision of consultations and counseling sessions, as well as follow-up of patients through home visits, school visits and telephone consultations.

It also called for support for advocacy activities and the formation of forums so that people with haemophiila can be encouraged to become their own advocates.

As a result of this report, HFU entered into a four-year WFH-sponsored twinning programme between GOS in London and Mulago Hospital.

One of Agnes’ great skills is that of bringing together complementary agencies and initiatives to the benefit of her patients. At present, WFH and SaveOneLife donate factor on a named-patient basis. Under the twinning programme, WFH will ship in factor for the Mulago staff to initiate prophylaxis for those with diagnosed haemophilia A or B. But with so few patients diagnosed, there is a need not only to enhance diagnosis, but also to raise awareness. So Agnes has been working for months with the Novo Nordisk Haemophilia Foundation on an awareness-raising campaign entitled “Save Lives By Knowing”. Radio and TV shows are the best way to reach people in Uganda, and Agnes has been regular on both (Figure 3). The Foundation has also worked on improving diagnostic capabilities by donating equipment to and training laboratory personnel at Mulago, by means of a workshop run by Dr Angus McCraw, formerly head of lab services at the Royal Free Hospital in London (see accompanying article by Natasha Kopitsis). These activities came together in December 2015 with a physician training workshop and a patient testing day (Figure 4) and information workshop attended and facilitated by a team from Great Ormond Street Hospital.

The GOS visit to Uganda

Over the course of five days, Agnes and her HFU colleagues accompanied Dr Khair, clinical nurse specialist Jemma Efford, and specialist haemophilia physiotherapist Nicola Hubert as they got to know Mulago Hospital haemophilia team and their patients.

Mulago is very large and has the bustle of a small town. Outside the children’s unit there are mothers and babies everywhere, and on every corridor on every level of the hospital there are patients queuing to be seen by the medical staff and visitors preparing food. Everywhere you turn, there are queues. Patients wait on trolleys, some with drips receiving treatment. It is noisy and feels chaotic, not least because there is much government-funded building work underway.

On our first day, Agnes took us to the hospital’s children’s unit, where we met Sister Mary, Mulago’s principal haemophilia treater. She occupied a cramped treatment room, dominated by a large fridge stocked with a small amount of factor. Another patient, an 8-year-old deaf boy with severe haemophilia B, waited patiently for his Factor IX, while she was busy dispensing factor to the mother of two boys with haemophilia. One boy was on traction elsewhere within Mulago: while playing he had jumped and slipped and sustained a fractured femur and his mother had to deliver his treatment to the right department. Sister Mary, it emerged, had been in the unit since 9.30 the previous night when she was called in to treat a 24-year-old man with haemophilia with a traumatic head wound. Later on, we saw him waiting to have a CT scan at a cost of ugs 150,000 (about £30). He told us he’d been the victim of a mugging. Fortunately the scan showed no damage.

Agnes proudly showed us the new haemophilia treatment room, the result of her lobbying of the hospital administrators. But it is only an interim measure, she said. If HFU can establish the service, it expects to get a larger haemophilia department in one of the new buildings.

The following day Agnes and her team took us out of Kampala to meet a family with three boys with haemophilia. Agnes had only spoken to them by phone and was keen to encourage them to come to the forthcoming screening event and needed to arrange their transport. They lived around 190 km south west of the capital; after negotiating cars, bikes, motorbikes, cows and rain-filled potholes it was nearly two hours before we finally left Kampala. Several hours later, after crossing the equator, we drove on through Masaka and numerous villages where children had never seen white people until eventually, down a long red-dirt track, we reached Bikira and found the house we were seeking.

The family assembled outside as we pulled up in front of the house. Agnes was surprised to see four boys and a sister, along with their father and heavily pregnant mother. Kajjimbo January was diagnosed a few years ago when he almost bled to death after knee surgery. His younger bothers Emmanuel, Richard and Ronald have not yet had a formal diagnosis but their swollen knees and wrists all indicate severe haemophilia.

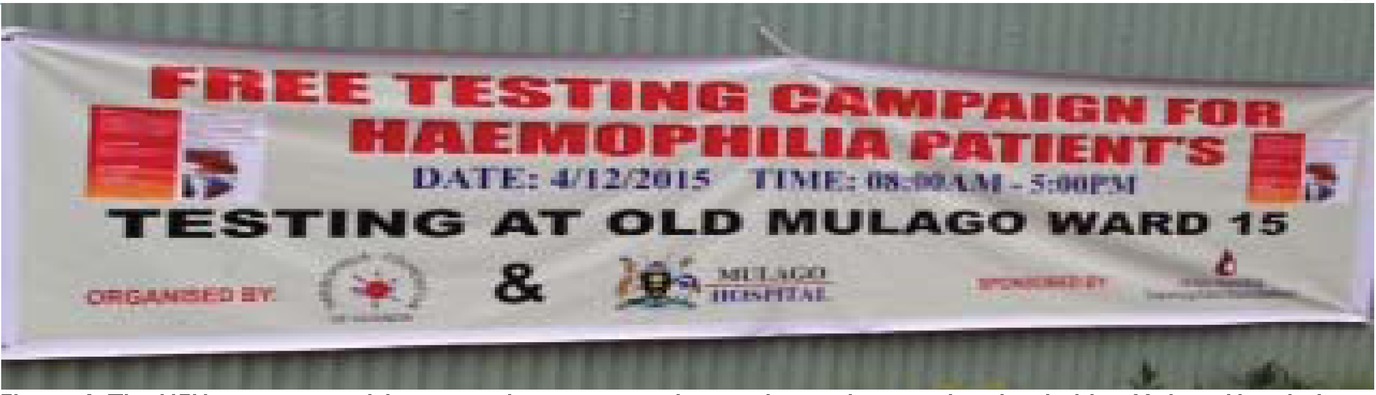

Figure 4

The HFU awareness raising campaign was geared towards a patient-testing day, held at Mulago Hospital

In fact, all four boys had bad joints. Although they could walk as far as the shops in the village, they were in pain when they get home: and none was able to do the things that other boys their age would routinely do such as collecting water or fire wood from the village. Only sister Josephine attended school. As the boys grow older, it seems unlikely that they will be able to work. There was another baby on the way. Asked if she wanted a boy or a girl, the boys’ mother said she’d had a scan: it was a boy and she knew he’d be just like her other boys.

Prophylaxis, of course, could change this bleak prognosis, but even with a formal diagnosis it seems an unfeasible proposition. The nearest hospital is in Masaka, some 66 km away. The only realistic treatment option at present is pain relief. We asked, through Agnes, what they would like to change about their lives. “The boys just want to go to school and be pain free,” they told us.

Before we left, Nicola and Jemma handed the children some toys, including a bottle of soapy liquid. Nicola showed the children how to blow bubbles. A smile lit up their faces as they saw the bubbles float away. For a brief moment they looked as carefree as any young boy should be.

Physician training workshop

The physician training workshop was moderated by Kate and her GOS colleagues and was attended by a “comprehensive care team in waiting”: obstetricians, paediatricians, nurses, dental surgeons, physiotherapists, midwives and pharmacists. The workshop started with all participants being invited to write on sticky notes “one thing you want to learn from today”. Many of the responses focused on wanting to know how to diagnose haemophilia, but some asked more complex questions around genetics. And someone asked about how to deliver home care. Around one quarter of delegates had never seen a patient with haemophilia – a situation that will change thanks to the work of the HFU.

In response to audience demand, the workshop focused on the genetics of haemophilia, as it became clear this was the source of some confusion. Many in our audience thought the textbook statement that carrier women have a 50:50 chance of having a boy with haemophilia would mean that a family with two boys would have one normal boy and one with haemophilia. Clearly not the case as the GOS team were able to show a photograph of the family with four affected boys they met earlier in Bikira.

In her overview of the haemophilia care offered by GOS to its families, Jemma sensitively drew contrasts with the care offered by Mulago and the challenges faced in Kampala. It was clear that the local clinicians recognised the resource and bureaucracy barriers but were keen to consider ways they could improve their service. The government has national outreach programmes for ensuring uptake of childhood vaccinations and these seem to be the ideal channels for promoting wider recognition of the signs and symptoms associated with inherited bleeding disorders.

Delegates recognized that Uganda was at the beginning of its journey to establishing haemophilia care. They questioned whether or not it was sustainable for a country to rely on factor donations, but recognized that cost meant factor was unlikely to be added to the country’s essential medicines list. One delegate suggested that tranexamic acid might be a realistic short-term alternative and urged clinicians to request the Medicines and Therapeutics Committee to add it to the hospital’s drug formulary.

The patient screening session

The patient-testing day attracted a large number of patients who claimed bleeding-related symptoms. It was clear that not all could be tested, so Kate set about taking clinical histories to identify those most likely to require testing. Some stories were heart-rending. For Kate, the stand out was the mother of a 5-year-old boy with haemophilia who brought a younger baby for testing. “She doesn’t yet know if her baby has got haemophilia. That’s a hard thing to take on board in the UK. But out here, having another child with haemophilia, and knowing there’s no treatment, must be catastrophic. At Great Ormond Street we’d have tested him at birth but she’s spent months just hoping he will not have haemophilia.”

For physiotherapist Nicola, it was the three brothers aged 23, 21 and 19, who could hardly walk but were incredibly cheerful. “They came in on crutches, with one in a wheelchair. It was heartbreaking.”

But there was hope too. Both Kate and Nicola were pleased to see Segwa Waswa walk in to the clinic using a single crutch. They had first met him a year ago, he’d been unable to walk or even to put both feet on the ground. As Kate explains: “Some time ago, following a knee bleed he was referred by a rehabilitation centre to a knee surgeon, who had biopsied his knee and removed a blood clot. He set the knee in extension. After being re-examined in theatre the knee was set bent. When we saw him last time he was crying a lot and needed morphine for the pain. Haemophilia A was assumed and he was given two weeks treatment with factor. The orthopaedic surgeon wanted to fix his knee in extension so he could get his foot to the floor, but we advised daily physiotherapy.” Today he was able to walk in to have his levels tested ... accompanied by two symptomatic uncles.

In all, more than 50 people attended and were tested. A few clearly had no bleeding history at all and just wanted to be tested. But around 45 patients had clear symptoms and were bled. The Mulago nurses were clearly well practised in taking bloods, although Jemma noted that they did not communicate with their patients in the way that UK nurses do (Figure 5). “It’s a completely different type of interaction.” But they had been taught the importance of good sampling and the impact this has on laboratory assays. Kate explains: “Before the screening day, usual practice was to insert a cannula, which proved complex in the many small babies and children that were being screened. Learning a ‘butterfly and syringe’ technique for blood sampling for screening (when no factor was to be given) resulted in better blood samples and less trauma for the children. There was no local anaesthetic cream, just stoical small boys who more often than not offered their arms out with no resistance. Loud crying was uncommon, but often a single silent tear was seen highlighting the plight of these small and vulnerable boys.”

Patient training camp

Some 116 children and family members attended a patient training camp day, funded by the Novo Nordisk Haemophilia Foundation team, where those who had been tested received their test results and an explanation of the implications.

The day inlcuded presentations from Kate and local clinicians, as well as patient stories and small group work. The questions that people asked focused largely on home care in the absence of factor, and the potential for treatment and cure in the future. But for most, of course, the main focus was the diagnoses following the previous day’s testing. In many cases, the diagnoses simply confirmed clinical signs, which generally meant confirming a severe diagnosis. But there were surprises, particularly in the number of diagnoses of possible von Willebrand disease. And there were bright spots. Earlier in the week we had met Gensa Joseph and his baby brother in Masaka. The 10-year-old had severe arthropathy preventing him attending school and could only walk with crutches (Figure 1). He’d previously been diagnosed (and an older brother had died) but his parents brought the baby for testing and were overjoyed to hear he would not suffer in the same was as his older brother. The relief for the whole family was clearly evident and was humbling to observe.

In all, Friday’s testing resulted in 50 new and confirmed diagnoses, leaving the total number of diagnosed patients in Uganda in excess of 100. This, of course, remains far short of the number that might be expected for a population of 36 million, but this is huge progress considering where the HFU was even just two years ago when Kate and Agnes first met and they had 20 patients with haemophilia, of whom only three had a formal diagnosis (Figure 6).

Much of this has been the result of Agnes’ tireless media campaigning. The presence of media representatives at both the patient testing day and the patient camp was clearly worthwhile with reports appearing in the press and on YouTube. Agnes is ensuring that the message is getting out: haemophilia results in painful and shortened lives but is a treatable condition if appropriate services are in place. But the political willingness to develop those services must also be in place and Agnes and the HFU team have continued their awareness raising work by focusing at government level.

Six months on … and looking forward

Following their return to London, the Great Ormond Street team put efforts into raising funds to support the HFU and the patients they had met in Kampala. By May 2016 this had resulted in the donation of a water tank to Mr Kajjimbo’s family, to save his four boys from the physical pain of collecting water from the local stream (Figure 7).

Dr Hilda Tumwebaze from Mulago Hospital was one of the attendees at the healthcare professionals training session delivered by the GOS team in December. Six months later, with funding by the Novo Nordisk Heamophilia Foundation, she spent time at the GOS haemophilia centre to see for herself how haemophilia care is delivered in London.

At Mulago, haemophilia is currently managed principally by the nurse team, with the ward doctors getting involved principally when patients have other comorbidities such as infections. Now that there is the possibility to diagnose, and more importantly to treat haemophilia in Uganda, she believes that more doctors will begin to consider haemophilia in those patients who present with bleeding, bruising and swollen joints. Clinicians, she says, “want to help patients and get a good feeling when they are able to do so. They want to know they can make a difference in patients’ lives.”

Dr Tumwebaze believes that in five years time Mulago will have established haemophilia clinics staffed by doctors, nurses, and physiotherapists, and that most patients will be managed as outpatients. Home treatment is likely to remain unrealistic due to lack of supply and the fact that many patients live too far away from Mulago.

The real game changer in Uganda, however, will be when hospitals other than Mulago start offering haemophilia care. For this, there is a great need to train more physicians, particularly in the hospitals further down the chain from Mulago. “The ideal would be to train the healthcare professionals working in the government-run level II health care centres, as for most people with bleeding disorders this would be the point of entry into the system – often after having been through the local witch doctors,” said Dr Tumwebaze. “At present, most of the workers in these level II centres would not consider a bleeding disorder in a child who presents with a painful and swollen knee but would assume it is an infection or an orthopaedic problem.” As a result, many will be treated with nothing more than mild painkillers while other patients will find themselves treated as orthopaedic cases, sometimes ending up with surgery. As Segawa Wasswa knows only too well.