Observations of a fibrinolytic effect were made by the Hippocratic school of medicine back in the 4th century BC, when it was observed that coagulated blood after death has the ability to undergo reliquefaction [1]. Investigators in the 18th and 19th centuries separately documented the spontaneous breakdown of blood clots, Jules A. F. Dastre coined the term fibrinolysis [1].

The haemostatic system in a healthy individual is in physiological balance between coagulation and fibrinolysis, the normal function of the latter leading to clot destruction and restoration of normal blood circulation. This balance may be upset in patients with inherited bleeding disorders who have normal fibrinolytic activity, such that physiological fibrinolytic activity may be sufficient to start bleeding after inadequate clot formation. In the acquired coagulopathy setting, e.g. trauma, hyperfibrinolysis is caused by activation of plasminogen activators and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Other than clearly demonstrable fibrinolysis in this setting, additional occult fibrinolysis appears to be detectable in those presenting with trauma and only subtly deranged routine clotting parameters [2].

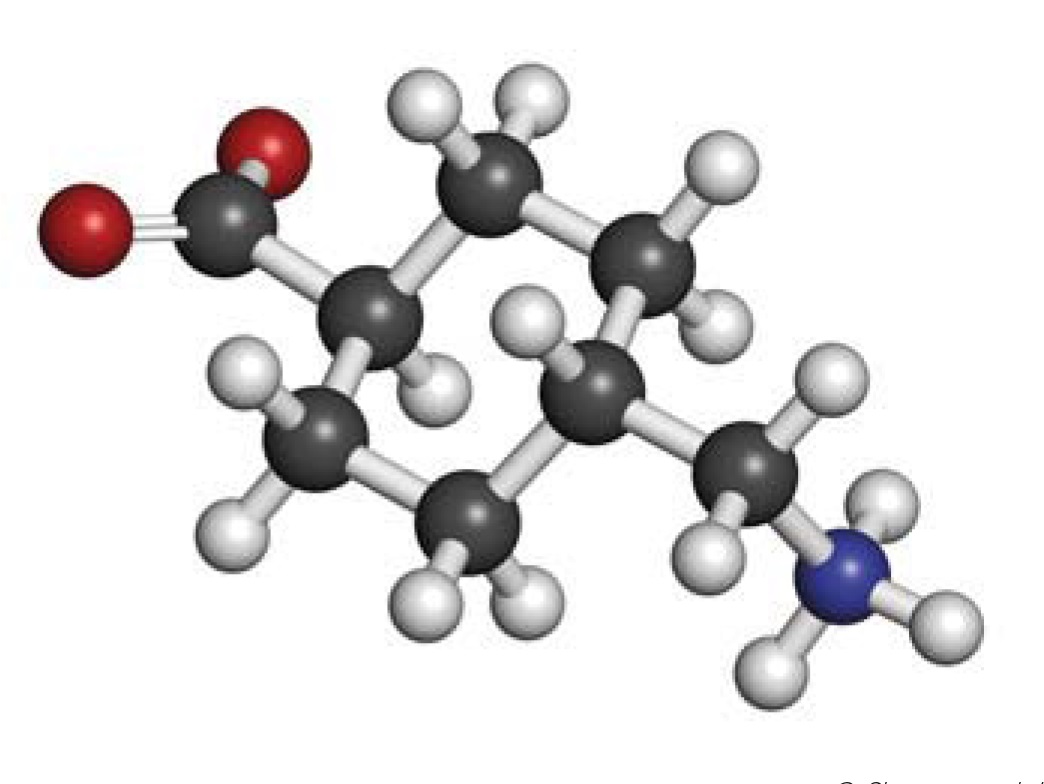

Antifibrinolytic drugs inhibit the breakdown of fibrin in blood clots. At present, three antifibrinolytic drugs are available: synthetic lysine analogues, epsilon-aminocaproic acid (EACA) and tranexamic acid, and the natural serine protease inhibitor, aprotinin. Aprotinin was isolated in 1930. Okamoto and colleagues discovered EACA in 1957 while searching for a substance with antifibrinolytic properties for use in prostatic and thoracic surgeries [3]. TXA was first reported as an inhibitor of fibrinolysis by Shosuke and Utako Okamoto in the Keio Journal of Medicine in 1962 [4]. TXA reversibly binds the lysine-binding site on the plasminogen molecule and inhibits the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, thus impeding fibrinolysis. It is 6 to 10 times more potent than other antifibrinolytic agents.

Only since the 1980s have these drugs found more widespread use, the evidence base for such use in acquired coagulopathies only emerging in recent years. In 2009, following the lifesaving results of the CRASH 2 trauma trial, TXA was included in the WHO list of essential medicines. Ongoing large randomised controlled studies on its application in post-partum haemorrhage, head injury and acute gastrointestinal bleeding are expected to report imminently [5, 6, 7].

Discussion

Over the decades, TXA has been used to treat heavy menstrual bleeding, to reduce blood loss in elective surgery, and in orthopaedic, cardiac and liver surgery, where it has been shown to reduce transfusion requirements. It has also found use in hereditary angioedema and skin conditions such as melasma. The CRASH-2 trial results show reduction in bleeding-related all-cause mortality when TXA is used in trauma compared to placebo [8]. There have been anecdotal concerns about thromboembolic complications, but without much documented evidence; indeed, a Cochrane review reported no increase in venous or arterial thrombotic events with TXA use [9].

Patients with haemophilia are known to have delayed and slow clot formation as well as reduced clot stability, which may be attributed to reduced velocity of thrombin generation, with subsequent delayed Factor XIII (FXIII) and thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) activation [10, 11]. It has been noted that haemophilic clots are made of thicker fibrin fibres and are thus more susceptible to fibrinolysis [12, 13]. An in vivo study by Hvas et al. showed that a combination of TXA and Factor VIII (FVIII) improved clot stability when compared with FVIII alone [14].

The use of antifibrinolytic agents in haemophilia most probably finds its origins in the observation by a haemophilic patient that consumption of roasted peanuts reduced tenderness in acute haemarthrosis [17]. Some authors have described possibility of using peanuts or peanut extracts to increase antifibrinolytic potential, although this is not based on trials [15, 16]. Verstraete et al. demonstrated peanut oil to have no statistically proven benefit in 92 haemophiliacs in a double-blinded trial [17].

Further trials in the 1960s concluded that antifibrinolytic agents as prophylaxis did not have a statistically significant effect, although further trials in larger cohorts were indicated [18, 19, 20]. Since prophylaxis with specific clotting factors has become the standard of care, this aspect has not been further investigated; however, a combination of clotting factor and TXA is the standard of care for bleeding and for treatment around surgery in many haemophilia centres in Europe [21]. In a retrospective survey, Schulman et al. reported a reduction in total blood loss of up to 50% using combined treatment with TXA and clotting factor replacement compared to clotting factor replacement alone during orthopaedic surgery [22].

Use of EACA and TXA alongside factor replacement to control local bleeding in dental procedures has been described since the 1960s [23, 24, 25, 26]. Sindet- Pedersen demonstrated reduced incidence of post-oral surgery bleeding and reduced factor usage with combined TXA acid use locally and systemically [27]. Waly et al. showed that children with haemophilia who received replacement products prior to dental extraction and local and systemic tranexamic acid developed less post-extraction bleeding than those who did not receive TXA [28], while Nuvvula et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of TXA on its own compared to factor replacement treatment in dental scaling procedures [29]. Mild to moderate haemophiliacs and patients with mild von Willebrand disease (vWD) may only need support with TXA alone for minor procedures (e.g. dental) or minor oral or nose bleeds, or with adjuncts like DDAVP [30]. More haemostatically challenging procedures, such as endoscopy with biopsy, still require the use of replacement clotting factor [31]. Cochrane reviews have acknowledged the effectiveness of TXA in dental procedures and as an adjunct in patients with anti-FVIII neutralising antibodies (inhibitors), whilst also highlighting the lack of well-designed, highquality randomised controlled trials [32, 33, 34].

Approximately 20–30% of haemophilia A patients treated with replacement clotting factor develop neutralising, alloantibodies against FVIII. This is considered the most serious complication in haemophilia therapy due to its impact on factor replacement efficacy, quality of life and resultant morbidity. Patients with persistent inhibitory antibodies require alternative therapy with the bypassing agents (activated prothrombin complex concentrate (APCC) or recombinant FVIIa (rFVIIa)) to achieve haemostasis either as regular replacement or episodic to cover acute bleeding episodes or surgery. Antifibrinolytics are used here to optimise efficacy of these agents. Bypassing agents have shown an overall efficacy of 80–90% [35, 36]. Dai et al. demonstrated in a laboratory study that the combination of TXA and APCC improved clot stability in FVIII inhibitor plasma without increase in thrombin generation [37]. A study by Holstorm et al. showed that treatment with APCC and TXA was safe with respect to serious adverse events such as thromboembolic complication and DIC in a limited number of patients (n=7) [38]. Tran et al. also reported the safety of a combination of TXA and bypassing agents [39].

Menorrhagia is common in women with bleeding disorders and is an extremely common presenting symptom in a number of disorders, including, vWD, platelet function disorders, Factor VII and Factor XI deficiencies, and in carrier states of haemophilia A and haemophilia B. Kouides et al. demonstrated that TXA is more effective in reducing menorrhagia compared to DDAVP [40]. The safety and effectiveness of TXA in menorrhagia and pregnancy has been demonstrated, and TXA may be used in pregnancy for women with severe bleeding disorders who experience vaginal bleeding [42, 43]. Although intrapartum and postpartum bleeding may often need appropriate clotting factor, TXA has been effectively used on its own or as an adjunct [44, 45, 46].

Conclusions

Tranexamic acid remains a versatile yet cheap drug with potential benefits in health services from the lowest to highest income countries. The increasing evidence base supports use of tranexamic acid in acquired and inherited bleeding disorders to reduce bleeding complications, reduce the need for blood product support and improve quality of life. However, there is still a need for well-designed randomised controlled trials to strengthen the evidence for its use in inherited bleeding disorders. Chaplin et al. provide an important pharmacy review in this issue of The Journal of Haemophilia Practice which contributes further to the literature from which investigators may justify future funding applications.