Haemophilia A is an X-linked recessive disorder associated with deficiency coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) and lifelong bleeding diathesis [1]. While bleeding episode are usually provoked by mild or moderately severe traumatic events in non-severe haemophilia, the clinical hallmark of severe haemophilia is the frequent occurrence of spontaneous bleeding devoid of apparent traumatic aetiology [1]. However, the coinheritance of thrombophilic genes would be expected to modify the haemophilic thrombohaemorrhagic balance, thereby reducing bleeding tendencies and positively influencing phenotypic expression of the disease. Factor V Leiden is the most common inherited form of thrombophilia in Europeans, where the prevalence is up to 15% in some population groups [2]. A well-known example of coinheritance of thrombophilia in European haemophiliacs is typified by the coinheritance of factor V Leiden mutation, which ameliorates the clinical phenotypes of severe haemophiliacs by reducing the ability of protein C to inactivate factor V. Consequently, factor V Leiden enhances the prothrombinase complex, thereby shifting the thrombo-haemorrhagic balance in favour of greater thrombin generation and haemostatic stability, with significant reduction in bleeding tendencies [3].

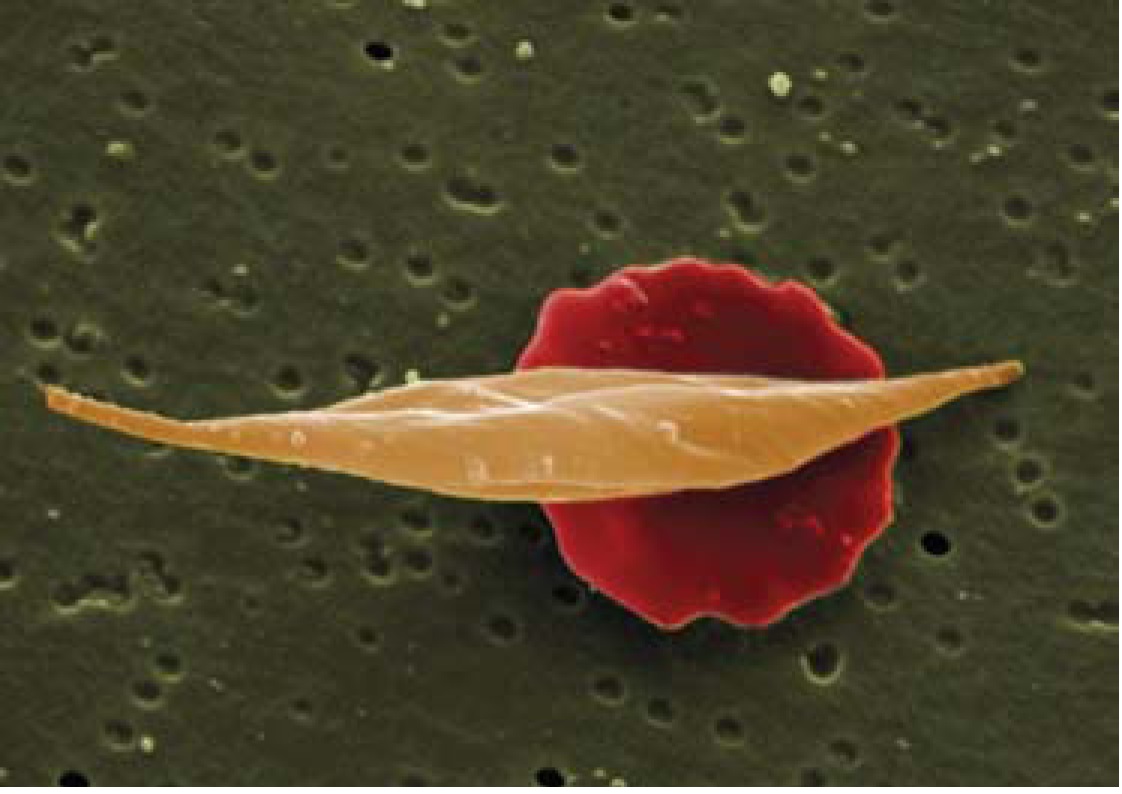

Sickle cell trait (SCT) is the heterozygous state for the sickle β-globin gene. Affected individuals have the Hb AS phenotype as their red cells express both Hb S (20-40%) and Hb A (60-80%) [4,5]. The predominance of Hb A in the red cells prevents sickling under physiological conditions, as a result of which the red cell life span is normal in SCT and affected individuals have normal life expectancy [6]. The SCT confers survival advantage by providing resistance against severe malaria in the tropics [7,8]. The frequency of SCT is up to 30% in tropical Africa, including Nigeria [9]. However, SCT also confers upon its carriers a high risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) as variously reported in the literature. A study conducted in 1992 reported a case of SCT with recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that could not be associated with any other known risk factor for DVT [10]. A much larger study reported by Austin et al. demonstrated that persons with SCT had an increased risk of VTE, the risk being stronger for pulmonary embolism than for DVT [11]; however, a prospective study by Folsom et al. suggested that SCT was associated with increased risk of pulmonary embolism but not DVT [13]. A study focused on a population in Northern Nigeria suggested that SCT synergistically increases the risk of DVT in persons with non-O blood groups [12]; it has also been suggested that hormonal contraceptives might pose a higher risk of VTE in black women with SCT than in black women with a normal haemoglobin phenotype [14]. A number of studies have reported cases of SCT patients with thrombosis affecting unusual venous vessels, such as the splanchnic and cerebral veins, as well as the superior sagittal sinus in the absence of any other known prothrombotic risk factors [15, 16, 17]. Contrasting with the aforementioned studies, an investigation by Pintova, Cohen and Billett failed to confirm the presence of any increased risk of DVT or pulmonary embolism among female patients with SCT even during challenging prothrombotic periods such as pregnancy and puerperium [18].

The elevated risk of venous thromboembolism in individuals with SCT was thought to be due to subclinical red cell sickling leading to increased activation of coagulation factors, as evidenced by elevated levels of d-dimers, thrombin anti-thrombin complexes and prothrombin fragments [19]. We therefore believe that the SCT can be considered as a hypercoagulable prothrombotic state and hypothesise that coinheritance of SCT may ameliorate the clinical phenotypes of severe haemophiliacs in tropical Africa. If our hypothesis is correct, severe haemophiliacs with SCT (Hb AS phenotype) will have lower frequencies of spontaneous bleeding episodes than those with normal Hb phenotype (Hb AA phenotype).

To the best of our knowledge, the relationship between SCT and haemophilia has not been studied previously. We conducted a retrospective analysis of the frequencies of spontaneous bleeding episodes among severe haemophiliacs with SCT and those with a normal Hb phenotype in order to determine the possible ameliorating effect of SCT on the frequency of spontaneous bleeding in haemophilia-A patients in Nigeria.

Patients and methods

The socio-clinical setting

As in many developing countries, FVIII prophylaxis is not usually available for patients with haemophilia in Nigeria. The few haemophiliacs who access tertiary hospitals usually present as emergency cases for on-demand therapy with fresh plasma, cryoprecipitate or FVIII concentrates, depending on product availability and affordability to the patient. Moreover, regular clinical follow-up is poor due to ignorance, poverty and logistical difficulties. This situation makes it very difficult to undertake prospective studies for any reasonable time period. The retrospective data available to hospital-based researchers, collected during bleeding emergencies, is usually scant and scattered, and few patients living in urban areas with tertiary health facilities have regular uninterrupted clinical follow-up for long periods. The predicaments of haemophiliacs and their healthcare providers within the low resource settings of developing countries are described accurately and in detail by O’Mahony and Black [20].

Type, area and period of study

This is a retrospective cohort study of severe haemophilia A patients with and without SCT that were managed with fresh plasma, cryoprecipitate or factor VIII concentrates for spontaneous bleeding episodes at the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital, Maiduguri, northeast Nigeria, during the period 1995–2007.

Patient selection and data retrieval

The clinical and blood product transfusion records of all patients with severe haemophilia-A who had one or more complete years of regular follow-up were reviewed. The type and number of presenting spontaneous bleeding episodes and haemoglobin phenotypes (Hb AA or Hb AS) of each patient were determined as documented in clinical and blood bank records. Patients with sickle cell gene in compound heterozygous states such as Hb SC and Hb Sβthal were not included in this study. All spontaneous bleeding episodes were counted, including minor bleeds that ceased spontaneously at home without the use of factor concentrates; however, non-spontaneous haemorrhages with recognisable precipitating traumatic events were not counted. Patients without at least one complete year of uninterrupted records of clinical/blood product transfusion records were excluded. All procedures in this study were conducted with informed consents obtained from parents or guardians of young patients with supplementary assent from older patients and the approval of local institutional ethic committee.

Diagnosis of haemophilia and haemoglobin phenotypes

The patients studied were known cases of haemophilia A, previously diagnosed on the basis of characteristic clotting profiles with low FVIII levels, as assayed by automated coagulometers or by the one-stage manual assay technique [21]. Patients were categorised as severe (FVIII level <1%), moderate (FVIII level 1-5%) or mild (FVIII level 6-40%) haemophiliacs [21]. Hb phenotypes were determined by haemoglobin electrophoresis at a pH of 8.6 on cellulose acetate paper, sickling test and haemoglobin quantitation. On the basis of the electrophoretic patterns, patients were categorised as normal (Hb AA phenotype) or SCT (Hb AS phenotype) [22].

Statistical data analysis

The type and number of spontaneous bleeding episodes were collated with respect to the patients’ Hb phenotypes. The mean annual number of bleeding episodes per patient was calculated separately for severe haemophiliacs with normal Hb phenotype and for those with SCT as shown in the formulae below:

Mean annual bleeding episodes per patient for haemophiliacs with normal Hb phenotype: [Total number of annual bleeding episodes for all haemophiliacs with normal Hb phenotype] ÷ [Total number of haemophiliacs with normal Hb phenotype]

Mean annual bleeding episodes per patient for haemophiliacs with SCT: [Total number of annual bleeding episodes for all haemophiliacs with SCT] ÷ [Total number of haemophiliacs with SCT]

Comparative analysis of the mean annual bleeding episodes per patient for the two patient groups was conducted using the t-test with p-values of less than 0.05 taken as significant. Statistical analysis was performed using computer software SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

During the period under review (1995–2007), only 15 male children with severe haemophilia A were managed for various types of spontaneous bleeding episodes. However, the follow-up documents were so irregular over the years that only 7 patients (aged 6-11 years at the time of data generation) had up to one complete year (12 consecutive calendar months) of uninterrupted clinical/blood product transfusion records. 4 patients had normal Hb phenotype, while the remaining 3 had SCT. The pattern and frequency of bleeding episodes and the mean annual number of bleeding episodes are shown in Table 1. Haemarthrosis, muscle haematomas, epistaxis, gum bleeds, gastrointestinal haemorrhage and haematuria were the predominant types of haemorrhage in the patients studied, irrespective of Hb phenotypes. However, patients with normal Hb phenotype had significantly higher mean annual bleeding episodes per patient in comparison with those with SCT (45±7 vs 31±5, p=0.033).

Table 1

Pattern, frequency and annual episodes of spontaneous bleeding among 7 severe haemophiliacs with respect to haemoglobin phenotype

Discussion

The small sample size in this study is a manifestation of socio-economic factors referred to previously, which militate against Nigerian haemophiliacs accessing medical care. As a consequence, many die at a very young age in the hands of traditional healers or in hospitals with inadequate resources for effective prophylactic and therapeutic management of the disease [20]. Nonetheless, the study revealed a pattern of bleeding episodes dominated by haemarthrosis, muscle haematomas, epistaxis, gum bleeds, gastrointestinal haemorrhage and haematuria – a pattern comparable with the findings of a previous study conducted in Pakistan, another developing country [23]. However, our study also revealed that patients with a normal Hb phenotype had significantly higher mean annual bleeding episodes per patient in comparison with those with SCT phenotype. Although the p-value of just 0.033 denotes only a modest statistical significance, the result suggests that severe haemophiliacs with SCT had lower frequencies of spontaneous bleeding episodes than those with a normal Hb phenotype. This finding is consistent with our earlier hypothesis, which was based on the hypercoagulability status and prothrombotic profiles associated with SCT as documented in previous studies [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,19].

During normal haemostasis, the plasma membranes of activated platelets provide the catalytic anionic phosphotidylserine-rich phospholipid surface for the assemblage of tenase (factor IXa-factor VIIIa) and prothrombinase (factor Xa-factor Va) complexes, which are critical for the intrinsic activation of FX and the common pathway activation of prothrombin respectively [24]. Previous studies have revealed that SCT causes subclinical red cell sickling that is associated with scrambling of membrane phospholipids, exposure of anionic phosphotidylserine phospholipid and release of phospholipid rich microvesicles, which contribute to the activation of clotting factors, leading to the development of hypercoagulability [25,26]. The sickle cell-derived phospholipid-rich microvesicles presumably cause hypercoagulability by increasing the activation potential of phospholipid-dependent coagulation complexes such as tenase and prothrombinase [24]. Moreover, some studies have shown that, in comparison with persons with normal Hb phenotype, persons with SCT have a higher absolute monocyte count, which is thought to be associated with increased expression of monocyte derived tissue factor (TF) [19]. The hypercoagulability due to monocyte-derived TF in SCT is probably aggravated by the presence of sickle cell-derived phospholipid-rich microvesicles as phospholipids are an important co-factor for optimal biological activity of TF in the initiation of the extrinsic coagulation pathway [24]. Hence, we deduce that SCT is associated with increased activation of all three main coagulation pathways, including the intrinsic pathway (via increased phospholipid effect on tenase complex), the extrinsic pathway (via increased expression of monocyte-derived TF and the effect of phospholipid on TF) and the common pathway (via increased phospholipid effect on prothrombinase complex) [19,24,25,26]. We may therefore infer that the reduction in frequency of spontaneous bleeding episodes in severe haemophiliacs with SCT as observed in this study may be related to hypercoagulability resulting from the combined effect of red cell sickling and its attendant scrambling and release of membrane phospholipids, as well as increased monocyte-derived tissue factor expression. In comparative terms, the effect of sickle cell-derived phospholipids on the prothrombinase complex in haemophiliacs may be viewed as similar to the effect of factor V Leiden, which essentially augments prothrombinase complex in haemophiliacs, thereby reducing their bleeding rates [3]. While we infer that SCT-associated hypercoagulability may offer some level of protection against frequent spontaneous bleeding in severe haemophiliacs, we acknowledge that this study is too small to lead to a categorical conclusion. Nonetheless, these findings call for further research to adequately and categorically answer the question as to whether sickle cell trait reduces the frequency of spontaneous bleeding in severe haemophiliacs.

Conclusion

The results of this study would suggest that coinheritance of SCT in patients with severe haemophilia may be associated with reduced frequency of spontaneous bleeding, which may imply better overall prognosis. However, the study has very important limitations, including its retrospective nature and the very low number of subjects. The findings should therefore be validated by a larger prospective study.