Inherited bleeding disorders comprise a varied series of conditions, including haemophilia A and B, von Willebrand disease (VWD), Glanzmann’s Thrombasthenia (GT), platelet function abnormalities and deficiencies in factor V, VII, X, XI and XIII. Most have their first clinical presentation in childhood [1]. All are characterised by a tendency to bleed excessively and a specific pattern of inheritance [2].

Inheritance in vWD type 1 is autosomal dominant (AD), while in vWD type 3 it is autosomal recessive (AR); each has a prevalence of 1 in 100 and 2-5 in 1,000,000 [1]. Haemophilia A and B are both x-linked recessive (XR) disorders, haemophilia A occurring in 1 in 5,000 male births and haemophilia B in 1 in 20,000 male births [3]. Disorders affecting other clotting factors are extremely rare and most are characterised by AR inheritance [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Globally, GT with AR inheritance has an incidence of 1 in 1,000,000, but is higher in populations where consanguinity is common [9].

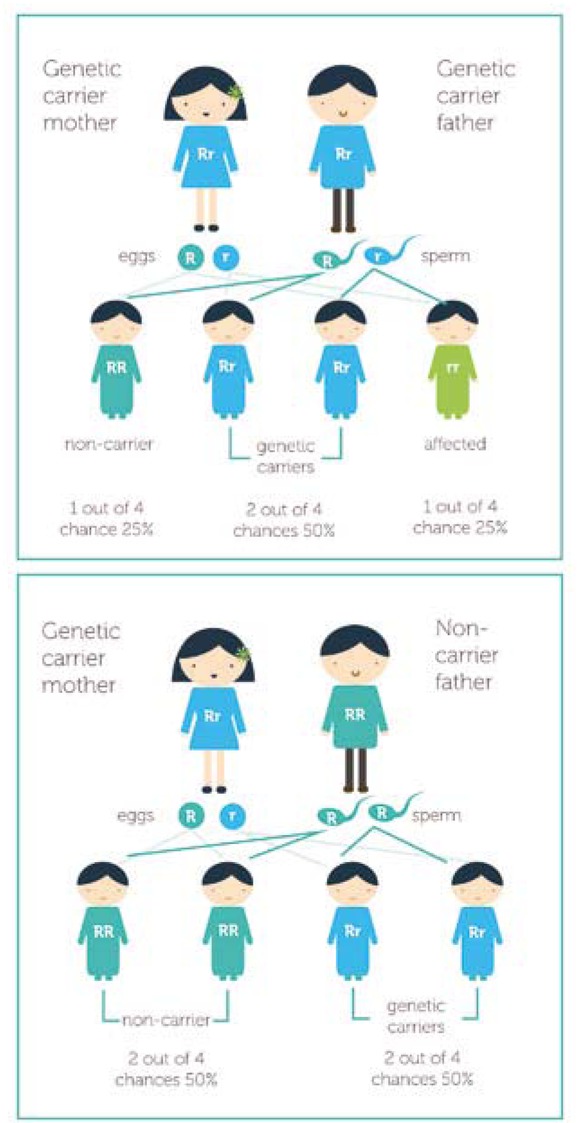

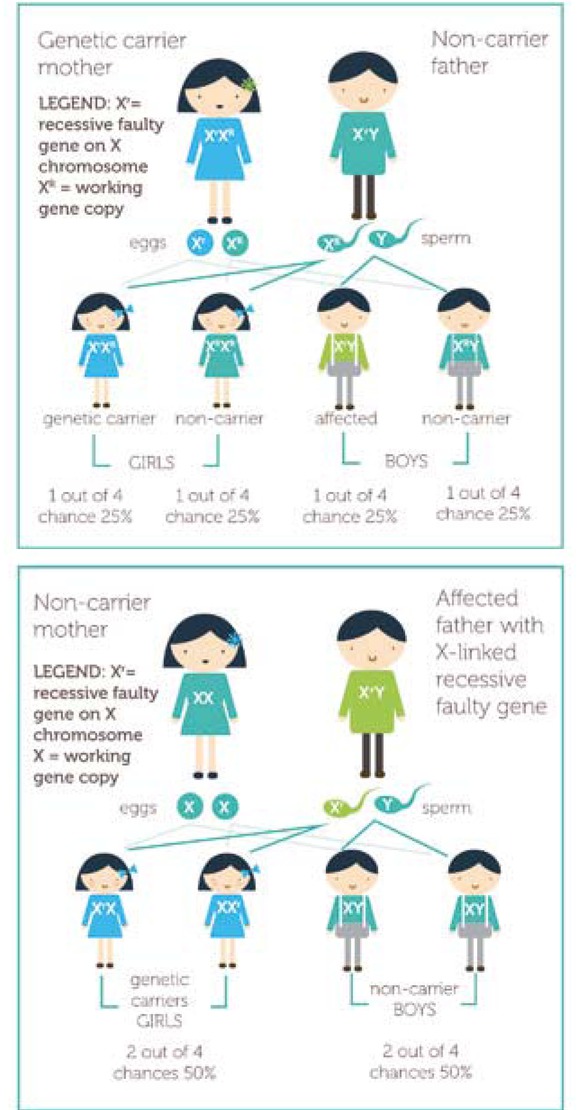

Autosomal recessive diseases are phenotypically expressed in offspring only if both parents carry the allele for the bleeding disorder (Figure 1). The disease generally presents early in the life of the child and can affect both males and females [10]. With x-linked recessive disorders (Figure 2), the mother carries the allele for the condition, which is phenotypically expressed in males and can be diagnosed early or later in childhood [10].

Figure 1

Autosomal recessive inheritance, where ‘R’ represents the working copy of the gene and ‘r’ is the faulty copy of the gene containing the recessive mutation [10]

Figure 2

X-linked recessive inheritance, where ‘R’ represents the working copy of the gene and ‘r’ is the faulty copy of the gene contained in X-linked recessive mutation [10]

In autosomal dominant conditions (Figure 3), one or both parents carry the faulty gene. When only one parent carries the mutation, there is an equal chance for the disorder to be phenotypically expressed in both males and females. If both parents carry the mutation, there is a 1 in 4 chance of their child being severely affected by the disease [10].

Figure 3

Autosomal dominant inheritance, where ‘d’ represents the working copy of the gene and ‘D’ is the faulty copy of the gene containing the dominant mutation [10]

Children’s understanding of inheritance

There is considerable psychosocial research describing children and young peoples’ understanding of XR, AR and AD genetic inheritance in many conditions, including how genetic information is communicated and how parents share genetic information within families. However, specific research in children and adolescents with inherited bleeding disorders has been limited. To date, only two studies have

measured children’s understanding of haemophilia genetics and inheritance:

In a 1992 study, Spitzer used grounded theory through semi-structured interview to collect data on the experience and understanding of haemophilia in 20 children aged 6-13 years [11]. Findings indicated that the children in the study had very limited understanding of their disease and how haemophilia is inherited.

In a qualitative study by Khair et al. in 2011, data on knowledge and understanding of genetics and inheritance were gathered using semi-structured interviews from 30 boys (aged 4-16 years) with haemophilia A (n=27) and haemophilia B (n=3) [12]. The children in this study had a good awareness of the genetics and inheritance of their haemophilia.

As both studies focused on haemophilia, which has an XR mode of inheritance, the results may not be relevant to other bleeding disorders. In addition, neither study included any standardisation in the interview questions used to measure the concept of inheritance and genetics in the different age groups. The difference in results between the two studies may, at least in part, be explained by improved accessibility to information by parent and child, better patient/parent education, and participants having grown up with a brother with haemophilia in the later study by Khair et al. [12]. Unlike the children interviewed in the study by Spitzer, those in the study by Khair et al. had access to the internet, which offers a source of instant communication, social interaction and networking with friends, as well as providing access to health information on a variety of topics, including genetics and inheritance [13,14]. Furthermore, by the time of the later study, there was a greater general awareness of haemophilia as a result of the infection of individuals in the haemophilia community from contaminated blood products [15].

Several studies have attempted to assess the age at which there is understanding of the concept of inheritance and what influences its development [16,17]. Younger children seem to comprehend that babies come from their mother’s tummies, but tend to have little understanding of the father’s role and show bias towards their mother when reasoning which parent they most closely resemble [17]. According to Williams and Smith, a child’s biological understanding of inheritance develops with age [18]. Older children and adolescents in the UK are now taught genetics and inheritance as part of the National Curriculum for Science and have a physiological understanding of inheritance [12,19,20]. Studies by Lindvall et al., involving young people and adults with haemophilia aged 13-25 years and over 25 years, showed that 69% and 96% of patients respectively were aware of inheritance [21, 22]. When Miller et al. asked patients over the age of 18 to rank their genetic knowledge of their haemophilia, around 80% of those who responded ranked their knowledge as high [23].

Despite this, adolescents and older children still hold many misconceptions and inaccuracies in their understanding of basic genetics, although such misconceptions are not only restricted to young people [18]. In a telephone-interview study by Lanie et al. involving adult participants, 34% with high school biology education thought that genes were located in every cell, 24% identified genes as being located in the brain and/or the mind, and the remainder either did not know or gave inaccurate explanations [24]. Moreover, Featherstone et al. found that those of white British heritage affected by genetic conditions and attending a clinic in South Wales often attributed their condition to fate or destiny [25].

Parental communication and understanding of genetic risks

Parents are the primary recipients of genetic information at the time of the initial diagnosis of their child [26]. Health professionals convey this information at a time when emotional responses may hinder the parent’s comprehension, which in turn may affect the information they pass on to their children. Studies by Sobel and Cowan and McConkie-Rosell et al. have shown that withholding information on genetic risk from children can have profound consequences for the child and family unit [27,28]. Previous studies have also shown that when genetic risk information is withheld from young people until they reach adulthood, it can affect their ability to cope, self-esteem, reproductive decision-making and family cohesion [27, 28, 29]. However, according to Tercyak et al., most parents believe that children have a right to genetic information that may affect their own health or that of the family, and that being party to such information can prevent or alleviate stress for the child and promote greater trust [30]. Although having the prime responsibility for disclosing this information to the child, parents acknowledge that it is a task they find difficult due to blame, guilt and stigma [31, 32, 33, 34]. Fear of causing distress, combined with the innate need to protect their child, means that many parents struggle to know when and how to tell their children about genetic risk.

Although never tested, it has been suggested that the mode of inheritance may influence how families learn about the inheritance of their genetic condition. XR inheritance facilitates the attribution of blame towards mothers more so than AR inheritance, where both parents contribute to the condition phenotypically expressed in the child [35,36]. The results of a study by James et al., echoed by findings in other studies, found that XR families had a moderate understanding of the mode of inheritance compared with AR families, overestimated the chance of an affected father having a son affected by the condition, and underestimated the chance of having a daughter who is a carrier [34,37]. AR families also overestimated the reproductive risks of children and young people affected by the disease [38].

Many people struggle to understand the concepts of risk statistics and probability. Indeed, Ulph et al. have highlighted the difficulties children and young people have in understanding probability terms [40]. Many young people rely on shared subjective judgments about features in the family phenotype, which are often characterised by how individuals view inheritance and the views of their parents, alongside some of the difficulties they may have in understanding risk probabilities [39]. Such misunderstandings have potentially harmful implications for children and adolescents, leading to confusion about the risks to themselves and their potential offspring, and possibly resulting in poor reproductive decisions, failure to attend genetic counselling services and low self-esteem [29,41].

Significance of establishing carrier status

The use of genetic testing to establish carrier status for genetic diseases with Mendelian inheritance is becoming more widespread. Meza-Espinoza et al. describe a carrier as someone with a balanced chromosome translocation that does not affect their health but whose children can inherit an unbalanced form with adverse phenotypic consequence [42]. Carrier testing and detection or prenatal diagnosis remains important in the care of young people with bleeding disorders. In haemophilia A and B, carrier detection after DNA analysis can provide definite answers with 100% accuracy for those women who are carriers [43]. Miller divided carriers of haemophilia A and B into three categories: obligate carriers, potential carriers and sporadic carriers [44]. Obligate carriers are either a woman with a son diagnosed with haemophilia or the daughter of a man with haemophilia. For potential carriers, the status is not clearly defined based on the pattern of inheritance; for example, a woman without a family history of haemophilia who has a son with haemophilia, or a women with a maternal relative with haemophilia. In the case of sporadic carriers, there may be no family history of the condition. Sporadic carriers may themselves have a bleeding history or may be identified when their child presents with unexplained bruising.

Few studies have sought the opinion of adolescents regarding the age at which they would prefer to be offered genetic testing. In a study by Jarvinen et al., young adult women who had genetic testing for either Duchene muscular dystrophy or haemophilia A as minors felt it should have been performed in their teenage or childhood years [45]. Another study by Sparbel et al. found that teenagers, on learning about their genetic status, were actively thinking about their future options [46]. McConkie-Rosell et al’s investigation of the opinions of young adult women with fragile X syndrome before and after having genetic testing found that most were in favour of carrier testing and the disclosure of genetic risk before the age of 18 [47]. Participants felt that it was important to have this information at an early age in order to have time to adjust. Participants affected by haemophilia at the age of carrier testing in a study by Thomas et al. favoured genetic testing soon after birth, during childhood and at any time up to adolescence [48]. However, not all adolescents and young people viewed the genetic testing offered to them in a positive light. James et al. interviewed a small group of adolescent females who had siblings with chronic granulomatous disease and found that they were against carrier testing for minors, and felt it should not be offered until the age of 18 years or older [49].

In studying the long-term psychosocial effects of carrier testing for XR conditions, Jarvinen et al. found no significant difference in well-being between the control group and the research population [45,50]. Conversely, studies by Jolly et al. and McConkie-Rosell et al. found temporary or specific differences between the two groups [51,52]. In recent years, concerns have arisen around the potential psychological and social harm of genetic carrier testing in children younger than 18, including psychosocial effects, lack of reproductive privacy and the threat of discrimination and stigmatisation [53]. These have been linked to children lacking autonomy in the decision to undergo genetic testing and the extent of their ability to assess the potential benefits and risks [54]. Current UK guidelines stipulate that carrier testing of children and young people should only be done in the expectation of clear psychosocial and medical benefits [55].

To date, only one systematic review of the literature relating to the genetic testing of young people has been undertaken. Rew et al. reviewed studies (n=56) relating to the attitudes and knowledge of young people and their parents around genetic testing [56]. Most were descriptive and focused on specific inherited disorders; only two considered haemophilia. The sample populations for all studies were biased towards well-educated white females. The results suggested that young people and their families may experience both harm and benefit from genetic testing, but showed relatively positive attitudes towards it.

Legal perspectives

Healthcare professionals are perhaps best placed to question the appropriateness of offering a diagnostic genetic test to a young person. In the case of carrier-status tests, or where symptoms have yet to develop and the purpose of the test is for knowledge, it would be easier to defer the test request by the parent or young person. Studies by Borry et al. and Rosen et al. on the attitudes of genetic counsellors and clinical geneticists towards carrier testing of young people indicated a greater willingness to provide the test if requested by a paediatrician rather than a parent [57,58]. For most young people under 16 years of age, the legal principles that apply were developed in the case of Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority [59]. In such a case, the clinician is required to make an assessment of competence under the Gillick principle, whereby the health professional must respect the young person’s request and must be satisfied that:

regardless of age, he/she is of sufficient maturity to understand the health professional’s advice;

the young person’s mental or physical health is likely to suffer unless the test is performed;

the young person’s best interest is paramount; and

the health professional cannot persuade the young person to inform his/her parents or allow the professional to inform them.

If the young person is between 16 and 18 years of age, the provisions of the Family Law Reform Act 1969 apply and the situation for the clinician is straightforward [59]. Section 8 of the Act states that children over 16 years of age can consent to a “surgical, medical or dental treatment” in the same way as any other competent adult who has followed the informed consent process. The legal concept of the informed consent process has three main elements: it must be given voluntarily; the person must be adequately informed; and the individual must be competent to consent. As genetic testing is a procedure used for diagnostic purposes, it can feasibly be regarded as a kind of treatment as referred to in the Act.

In a survey conducted by Borry et al in 27 European Union member states, 177 clinicians were asked questions on the genetic carrier testing of minors, including (i) the recommended age for informing children of their carrier status; (ii) the age at which they would allow minors to request a carrier test with parental consent; (iii) the age at which a carrier test could be requested without parental consent [60]. The age suggested by the UK respondents for the above three questions (n=17) was around two years lower than the European average, with the Gillick ruling thought to be an influencing factor. However, the reasoning behind carrier testing for bleeding disorders is different to genetic testing more broadly speaking, as it is undertaken with a view to ascertaining the risk of having an affected child. Girls with low levels of FVIII and FIX may suggest carrier diagnosis in haemophilia A and B respectively without any need for genetic testing. Those with levels of clotting factor less than 40% have a bleeding risk of three times the normal [61]. Hence, carriers of haemophilia with a diagnosis based on factor level may face many bleeding symptoms that must be managed appropriately.

In whose best interest?

Discussion around the merits and disadvantages of carrier testing has centred on the child’s autonomy and compromise of the young person’s confidentiality, as well as possible harms and benefits [62,63]. However, it is difficult to determine the psychosocial harm and benefit of carrier testing in childhood. Researchers have identified a number of potential concerns around carrier testing in children and young people, including change in perception of self within the family unit, difficulty integrating with peers, possible feelings of worthlessness, discrimination and stigmatisation, and possible problems with autonomous decision-making [64, 65, 66]. The arguments in support of carrier testing in children and young people put forward by Elgar and Harding and Clayton are that it gives the young person the opportunity to adapt to the genetic knowledge in their formative years before making choices on reproduction and marriage, and can avoid parental anxiety and uncertainty which the young person may find difficult [67,68]. According to Ludlam et al., carrier testing for females who are potential carriers of haemophilia should be offered at the point when the young person is able to give informed consent and understands the issues concerned [69].

In a study by Wehbe et al., adolescent females at risk of being fragile X syndrome carriers (n=53) were interviewed in-depth to identify the optimum age for exercising autonomy regarding genetic testing [70]. The study identified several phases of awareness about fragile X syndrome, including knowledge confirming carrier status based on genetic testing. The results highlighted the optimum time for awareness of the possibility of being a carrier as during the preadolescent to adolescent years. This is consistent with the results of the study by Jarvinen et al., where participants with a family history of either Duchenne muscular dystrophy or haemophilia A believed that the age of carrier testing should occur during childhood or adolescent years [45].

Disclosure

Open communication within families around haemophilia carrier status can raise awareness of the risk factors in daughters who may be affected, and help to inform and prepare them for future reproductive issues [71]. However, the issues around when and what parents should tell their children about their genetic risk status can be complex, as can the need to let “significant others” know [31]. Family communication patterns play a key role in the sharing of any family history of carrier testing and how the risk status is perceived and managed [72,73]. Where disclosure of genetic risk is concerned, Kenen et al. categorise family communication styles into five types [74]:

open/supportive, where children and young people, parents and significant others freely discuss the disease experience;

blocked indirectly, where boundaries are set around topics of discussion which are unacceptable and acceptable, often by non-verbal or silent means;

blocked directly, where overt boundaries dictate which topics are acceptable or unacceptable;

self-censored, wherein, due to the sensitivity and comfort level of one person to another, conscious limits are set; and

third party, in which another person’s involvement is necessary to conduct discussions on an individual’s behalf.

A meta-analysis by Wilson et al. describes disclosure of genetic information not only as an event for information transfer, but involving individual, familial, sociocultural and behavioural dimensions [75]. Factors known to affect the process of disclosure include the nature of the disease, mode of inheritance, family communication style and the individual’s coping strategy. As the responsibility for disclosing genetic information to children ultimately lies with their parents, the manner in which the parents communicate this information may impact on the extent of the disclosure of genetic risk [75,31]. Generally speaking, parents have an overwhelming need to protect their children from distressing information, but also understand that the child needs access to the information at an appropriate time to enable them to make key life decisions [31].

Disclosure to family members is dependent on a number of factors, including the perceived benefits and risks of doing so, closeness of family members, sense of shared responsibility, emotional readiness to disclose, level of certainty of the risk, and how family members may react [31]. Many studies on disclosure have focused on genetic conditions such as cystic fibrosis, Huntingdon’s disease, hereditary ovarian and breast cancer, and haemophilia A [76, 77, 78, 79]. In these studies, common reasons for disclosure include obligation to disclose, the need for support, sense of responsibility toward the younger generation, and close social relationship with a family member. Communication of genetic testing within the nuclear family seems to occur systematically and frequently [75].

Other studies assessing the disclosure of test results found that although participants shared the results of their tests with others, disclosure was selective. In a study by Anido et al., the provision of information about fragile X syndrome to partners was largely dependent on how the status of the relationship was perceived (i.e. whether or not it was considered a serious relationship) [80]. Children and young people may worry for several years about their potential carrier status if it is not confirmed before they reach the age where they can be legally tested without parental consent, particularly if they begin a sexual relationship. Moreover, these worries may not be raised or addressed for fear of upsetting their parents [41,49]. The period of adolescence can be a stressful time for any young person due to the many life changes that occur at this age. In the presence of a genetic condition, this may be even more so. Time may therefore be of the essence in terms of young people being able to consider and absorb genetic information before it becomes relevant to them. Studies of other genetic conditions have observed that late disclosure may hinder reproductive decision-making, for example [29,37].

Nondisclosure within families around the results of genetic carrier testing may be influenced by guilt and anxiety, lack of closeness within the family and/or a desire to protect the child from troubling information [31,76]. Participants in a study by Stoffel et al. were reluctant to share information for reasons including lack of closeness, a desire not want to worry the child/young person, and concern that they may not know how to interpret the results [81]. Furthermore, studies by Beeton et al. and Cassis found that nondisclosure of participants’ haemophilia was due to fear of rejection by others and a perceived lack of understanding of their condition [82,83].

Conclusion

Inherited bleeding disorders can have a profound impact on the quality of life of affected individuals, as well as children, young people and significant others who are carriers of the condition. Many studies involving inherited genetic conditions demonstrate that children and young people have a good awareness of the genetics and mode of inheritance, albeit there are few studies involving inherited bleeding disorders. The haemophilia-specific study by Khair et al. demonstrates children’s understanding of genetic knowledge [12]; however, similar findings in studies by Lindvall et al. are incidental [21.22]. Having an effective tool to elucidate the genetic risks and modes of inheritance of inherited bleeding disorders would support parents, nurses and health professionals in providing better explanations in response to questions posed by children and young people about their known or potential conditions.

As emphasised throughout this article, children and young people are just beginning to appreciate the implications of the genetic risk of inherited disorders with common Mendelian inheritance patterns, as well as the possibility of their carrier status. By understanding what children and young people with these conditions want to know, healthcare professionals can provide optimum information during clinic visits so as to meet their disease-education needs. The clinician’s role in decision-making for carrier testing in children and young people is dependent upon the age of the young person, the Gillick principle and the Family Law Reform Act. In reality, the decision-making process in the offering of genetic testing is based on the principle that the welfare of the young person is paramount. Perhaps the main influence on the accuracy of the information shared with children and young people is the communication pattern adopted within families. These can be altered by health professionals to help with disclosure issues as the individual approaches key life decisions.