A child’s diagnosis of haemophilia is literally life-changing in its effects on both the child and the parents, who face a future of managing bleeding risk while trying to provide the child and his siblings with as normal a life as possible. In recent years, better access to clotting factors and the availability of prophylaxis have brought that aim within reach for many families. Home therapy offers independence and autonomy, and is now the preferred management option; but learning to administer treatment and manage risk depends on the resilience and confidence of the child and his family.

Wider access to treatment has been associated with growing interest in the family’s role in management, and is reflected in increasing research into the psychosocial impact of living with a child with haemophilia. Understanding how such demands affect parents and families who live with the daily threat of bleeding can help health professionals provide effective support. This review aims to summarise the key findings from recent evidence.

Methods

A literature search was carried out on PubMed on 19 November 2015 using the terms (caregiver OR parents) AND (cost of illness OR quality of life) AND coping AND blood coagulation disorders. The Social Sciences Database (SSRN eLibrary, www.ssrn.com/en) was searched on 6 January 2016 using the terms (haemophilia OR hemophilia) AND (bleeding OR coagulation).

Abstracts of the publications retrieved were screened for a primary focus on the carers, parents or family of children with haemophilia, addressing its psychosocial impact, economic implications and associated coping mechanisms. To maintain the focus on haemophilia itself and on primary research, publications about bleeding disorders other than haemophilia, those concerning patients with haemophilia and concurrent viral infection and reviews were excluded. Studies in which parents’ views were not analysed separately from patients’ views were also excluded. Further relevant information was identified by searching the citation lists of relevant publications. A cut-off of papers published from 2000 onwards was applied to limit the review to evidence most likely to be of current relevance. The search strategy retrieved 23 relevant publications, of which three were interventional studies and the remainder were observational studies.

Results

Observational studies

Eight focus group/interview-based studies using focus group or interview-based methodology were divided into three categories, which are not exclusive:

These qualitative studies used face-to-face interviews and focus groups to document parents’ views. The value of focus groups was that participants were able to share experiences, whereas individual interviews offered confidentiality [1]. Interviews were sometimes specifically described as semi-structured to ensure that key issues were addressed. Transcripts of the meetings were analysed and interpreted by an author [2,8] or, after coding, by analytical software capable of identifying significant themes that were subsequently reviewed by the authors [1,3,4,6,7]. One study did not describe its methodology [5]. The interviewers/focus group leaders were usually the authors or not specified [1,2,3,4,5,8]. One study noted that they were not the people involved in providing clinical care so that participants would feel able to be open and honest about their experiences [6] whereas a clinical psychologist conducted the interviews in another study [7.] In some studies, participants were provided with transcripts for approval [1,6] Participants were often recruited from a selection of (or sometimes all) patients registered at a specialist clinic (though not necessarily a haemophilia centre [8]). In one study, participants were ‘strategically chosen to achieve a span and spread in age and experience’ [2].

Results

Interviews focusing on parental experience identified several common themes (Table 1). All noted the trauma associated with being informed of the diagnosis, variously described as bearing the brunt of the diagnosis [3], shock, and feeling overwhelmed and vulnerable [1,2]. This is associated with perceived threat to the child’s well-being, but also with guilt, loss of self-esteem and sadness that could potentially lead to isolation of the parents, over-protectiveness of the child and heightened sensitivity about lost opportunities compared with the child’s peers [1]. Parents also described guilt at neglecting siblings and when a sibling was found to be a carrier [2]. This phase, described as a ‘need to gain control’ [3], was addressed through support from health care staff and learning about haemophilia and its management – a process labelled ‘mastering knowledge of haemophilia’ [2].

Table 1

Interview-based studies focusing on parental experiences

| Study and Location | Participants | Themes (as phrased in the publication) |

|---|---|---|

| Beeton et al, 2007 [1] UK | 12 parents of children with severe haemophilia (of 41 invited). Children aged 18 months – 13 years | Coming to terms with finding out about the diagnosis Learning to recognise bleeds and to administer factor replacement Managing social contacts and feelings of isolation Being an advocate for the child |

| Myrin-Westesson et al, 2013 [2] Sweden, Norway | Mothers who were carriers (n=13) and have children with moderate/severe haemophilia | The time after diagnosis Feeling sad about the child’s illness A sense of being accused Unable to protect the child from suffering Being overwhelmed by worries and fear for the child A feeling of facing an overwhelming situation The turning point Capturing crucial knowledge Sharing the burden and sorrow with others Reconciliation with a changing life Reclaiming a sense of security Adapting professional life to the new situation Changing and growing as a person from the experience Being hopeful |

| Little et al, 2016 [3] Australia | 6 mothers and 1 father aged 25 – 48 (child aged 6 months – 15 years), not living near a specialist centre | Bearing the brunt of diagnosis If you can’t help me, who can? Tackling the challenges of treatment I need you to understand |

Experience with health care may not be pleasant; hospital attendance for bleeding episodes is stressful, there may be lack of continuity of medical and nursing staff and access to specialist care may be unsatisfactory [3]. Parents felt they had to be assertive in order to obtain the best care for their children [1]. They reported difficulty in coming to terms with treatment, whether through assisting health care staff to administer injections to a resistant child [1], having to administer injections themselves [2] or because the treatment regimen dominated family life [3]. The child’s reaction to treatment is an important determinant of how well the parents cope [3]. Use of prophylactic treatment and becoming competent at administering injections was described as ‘life-changing’ [1, 2, 3] and reducing ‘the sense of helplessness and anxiety associated with the unpredictability of bleeds’ [3]. However, it may also be associated with increased anxiety as a result of the increased responsibility for treatment [1].

The ongoing impact of having a child with haemophilia was characterised by awareness of the importance of resilience to external (dealing with other people) and internal (perceived threat to the child and family) challenges [1]. The ever-present risk of a bleeding episode meant that haemophilia was never forgotten or ignored, and the occurrence of an episode was a setback for parental confidence [1]. Others may not understand the ‘depth of the difficulties and responsibilities’ parents face on a daily basis [3]. Support from partners, family, friends and employers was important in coping with these challenges, as was involvement with national haemophilia societies [2,3].

In a UK study, mothers often assumed most responsibility for care [1]; this issue was not addressed in the more recent Australian study [3] and the Swedish study involved only mothers [2]. All described the importance of understanding and flexibility from employers, but women also reported having to reduce their hours of work or give up their jobs [1,2].

Three studies that specifically focused on the family [4, 5, 6] broadly support the findings of interviews exploring more general parental experiences (Table 2) [1, 2, 3]. Parents of children attending UK specialist treatment centres valued home-based treatment as it is less stressful, less disruptive than having to attend hospital and normalises haemophilia management as part of domestic life [5]. Nevertheless, some lacked confidence about administering injections, reporting difficulty in coping with an uncooperative child with the increased responsibility for treatment and concern about the risk of contamination of medication. Anxiety and the imposition of restrictions on the child’s activities exacerbated some concerns, leading to stress; but the extent to which children’s leisure was limited was variable. Support from specialist (but not non-specialist) health care staff was important.

Table 2

Interview-based studies focusing on family communication

| Study and location | Participants | Principal findings |

|---|---|---|

| Gregory et al, 2007 [4] UK | Semi-structured interviews on family disclosure processes. Families of patients at one centre (10 cases and 32 carriers). | Contrast of information provision within family and by medical staff Family has practical knowledge provided when needed; normalises haemophilia in everyday life Information sharing determined by factors specific to the family |

| Shaw et al, 2008 [5] UK | 24 families, children aged 8 – 12; 9 on home-based prophylaxis, 8 on home-based on-demand, others on-demand at hospital. Includes 4 families with von Willebrand’s disease. | Home-based prophylaxis normalises management Parents initially find injections traumatic Increased responsibility stressful Empowerment comes with mastery of technique |

| Furmedge et al, 2013 [6] Australia | Focus groups (n=15 parents) recruited from a convenience sample of parents of children with haemophilia who attend the RCH Haemophilia Centre and had administered factor concentrate to their child via a port. | Four main themes: Dealing with fear and anxiety (hurting child, fear of getting it wrong) A supportive learning environment (fostering confidence, respect for parent and child) Establishing a ritual and empowerment (comfort and control for child, aid to parental learning) Empowerment and liberation (taking over child’s treatment, familiar environment, getting our life back) |

Parental experience of administering factor replacement therapy via an implanted central venous access device (CVAD) was explored in a focus group of 15 parents recruited from a specialist haemophilia centre in Australia [6]. Their comments described a journey from initial anxiety about harming the child (through the act of inserting the needle or by introducing infection) to growing confidence as a result of learning in a supportive environment and establishing a ritual. Having a CVAD was described as ‘life-changing’: parents felt empowered when they assumed control of their child’s treatment after ‘a life dominated by bleeding episodes’ and repeated trauma associated with venous access.

UK parents distinguished between the quality of information they received from clinicians about carrier status and risk (medical information about haemophilia and its genetics) and the way in which the topic was discussed within the family (a context for the reality of living with the condition) [4]. Haemophilia was normalised by the family, whereas medical provision was perceived as serious and formal. This study notes that the content and timing of information transfer from parents to children (for example, disclosure of carrier status) depended on their particular circumstances, and that family values influenced how the information was interpreted (for example, value judgements and overt reassurance about coping that went beyond what health care staff would offer).

An Italian study provides further information about how home-based haemophilia management becomes normalised within the family [8]. Thirteen parents of children treated with on-demand therapy were interviewed about the implications of living with a child with haemophilia; the interviews were repeated five years later with three families whose children had started prophylactic therapy. Analysis identified four themes from the first interviews and five from the second (Table 3). The outcomes were consistent with other studies of how families respond in this situation. Normalisation comprised phases of learning to live with haemophilia after the shock of diagnosis and integrating management into daily life. On-demand treatment was associated with feelings of trauma and interference in daily living. Notably, the responses of some families suggest they considered living with haemophilia to be incompatible with normal life. Switching to prophylaxis relieved these stresses, but brought difficulties associated with treatment burden in the longer term. The family’s relationship with medical staff was an important determinant of how they perceived haemophilia management. In conclusion, the authors suggest their research shows ‘that prophylaxis requires intense cognitive, affective, and practical efforts to achieve family normality, which can be rediscovered by accepting the new condition and refocusing attention on the normal developmental needs of the child and the other members of the family’.

Table 3

Interview-based studies focusing on home care

| Study | Location | Participants | Principal findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emiliani et al, 2011 [7] | Italy | 13 parents of 10 children treated on-demand; repeated 5 years later with 3 families who began prophylaxis. | Computerised text analysis identified several themes in each set of interviews, mostly consistent with the findings of other studies, but notably suggesting that some families considered haemophilia is not compatible with living a normal life. |

| Ergün et al, 2011 [8] | Turkey | 20 mothers consecutively presenting at a specialist centre with a haemophiliac son. | Low educational attainment Lack of education about haemophilia and its management Excessive supervision of child Lack of medical support Personal sadness common, but minority said their lives were limited by child’s haemophilia |

In Turkey, the challenges faced by mothers providing home-based care for children with haemophilia were both personal and practical [8]. Of 20 women consecutively attending a haematology centre with their children, 35% could not read or write, 15% were educated to high school level, and 15% had poor mental health status. Many had not received education about haemophilia (40%) or dealing with accidents (55%), and almost half constantly supervised their child. Three-quarters reported difficulty in obtaining clotting factors and 85% wanted help administering treatment. Although 70% expressed sadness and were troubled that their child had haemophilia, only 23% reported that caring for their child had limited their lives. The authors advocated providing support via the local haemophilia society, support for home-based care and improved education.

Quantitative studies

Many studies have used a range of validated tools to quantify the impact on parents of living with a child with haemophilia. The parameters measured fall into three non-exclusive categories:

quality of life or caregiver burden;

anxiety or depression; and

competence, parenting skills and satisfaction/interference with daily living.

Quality of life/caregiver burden

The studies assessing quality of life or caregiver burden are summarised in Table 4. Overall, having a child with haemophilia is associated with impaired parental quality of life. While not consistently reported as statistically significant, and in one study not evident for the cohort as a whole [16] most studies identify problems associated with haemophilia in at least some aspects of life. The study that reported no overall impairment of quality of life found the quality of life reported by parents of children with haemophilia was higher than among parents of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis or type 1 diabetes [16].

Table 4

Studies using quantitative assessment: quality of life or caregiver burden

| Study and Location | Participants | Tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dekoven et al, 2013 [9] US | 261 haemophilia patients with inhibitors and their caregivers were identified from attendance at educational events. 103 agreed to participate, of whom 56 (58%) were caregivers. 70% of children had inhibitors and most were treated with immune tolerance induction therapy. | Caregiver burden measured by 5-point Likert scale for how much they were bothered by their child’s haemophilia (‘not at all’ / ‘a little’ / ‘moderately’ / ‘considerably’ / ‘very much’). | Caregivers who reported being bothered by their child’s haemophilia reported greater impairment of health-related quality of life for their child. This was statistically significant for patients aged 8–16 years (not tested in younger age group due to low numbers). For 4–7 year-olds, parental scores statistically significant impairment in domains of family and friends. For 8–16 year-olds, parental scores statistically significantly impairment in domains of family, treatment, relationships, dealing with haemophilia. Asked what bothered them about their child’s haemophilia, parents most frequently reported emotional stress associated with the disease, financial burden, problems associated with administering treatment and dealing with child’s pain. |

| DeKoven et al, 2014 [10] US | 681 caregivers of children with haemophilia identified by an advocacy group agreed to participate; 310 participated. 30 children had inhibitors. Most caregivers were mothers. | Online questionnaire developed from research with caregivers and literature review, incorporating the generic tool CarerQoL. Six burden domains were defined: emotional stress, personal sacrifice, financial burden, medical management, child’s pain, and transportation. Validated by 3 caregivers. | The median total burden score and VAS score were significantly higher for parents of children with inhibitors. The greatest differences were in the domains of personal sacrifice, transportation (exhausting, required more planning), financial burden, emotional stress, managing illness and the child’s pain. They were also more likely to have less time for themselves due to caregiving responsibilities, more difficult to relax, gave up things because of haemophilia, and life didn’t match expectations. CarerQoL: caregivers of patients with inhibitors perceived a poorer quality of life. They reported fulfilment, support and no relationship problems with the child but also, compared with carers of children with no inhibitors, more parents reported problems with mental and physical health, financial problems because of care tasks and problems combining care tasks with everyday activities. Current inhibitor status significantly correlated with caregiver burden. |

| Geerts et al, 2008 [11] Netherlands | Comparison of pre- (n=9 pairs) and post-transition (n=8) patients and parents (plus 5 parents alone) attending haemophilia centres. 70% of children had high titre of inhibitors, age >14. | Haemo-Qol-A, Parental Illness-Related Distress | No differences between parents of pre- and post-transition patients in reported worries about transition. Mothers, but not fathers, were more worried about transition than their sons and more worried about medical issues than transition. Parental illness-related distress was no different pre-and post-transition for mothers, but fathers had greater illness-related uncertainties and fears post-transition than pre-transition. Post-transition parents rated their son’s quality of life worse than pre-transition parents. Paternal and maternal estimations of their son’s quality of life were negatively correlated with worries about the transition and with their own and their partner’s illness-related distress (significant only for fathers). Patient and parental worries about transition were interrelated with parental distress |

| Kodra et al, 2014 [12] Italy | Parents (n=17) and children recruited through haemophilia societies. | Online survey using EuroQol. | Quality of life scores were higher in caregivers than adult patients, but not children. More caregivers reported problems (vs none) with mobility, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression; fewer reported problems with self-care and usual activities. Overall, scores for caregivers tended to lie between those for children and adults with haemophilia, except for anxiety/depression, where more caregivers reported problems. |

| Lindvall et al, 2014 [13] Sweden, UK, Canada | Caregivers of children <18 with inhibitors (n=39), without (n=37) and healthy children (n=67). Recruited from haemophilia treatment centres. | SF-36, Caregivers’ Burden Scale | 20 of 23 children with inhibitors were receiving immune tolerance induction. For caregivers of children with inhibitors, more were single and fewer in full-time employment or not working compared with children with no inhibitors or healthy children. Health-related quality of life scored worse for caregivers of children with haemophilia than healthy children, but there was no difference by inhibitor status. Positive inhibitor status was associated with greater interference with daily life, and a worse score on Caregiver Burden Scale overall and in the domains of general strain, isolation, disappointment and environment; there was no difference for emotional involvement. Impact on family: caregivers of children with inhibitors reported a significant negative impact on their lives in the financial, social, general negative and sibling domains |

| Bullinger et al, 2003 [14] Germany, Italy, France, Spain, UK, Netherlands | 330 parents; recruitment details not provided. | Parents filled out a questionnaire similar to Haemo-QoL and were asked to assess their children’s QoL, their own QoL and their perception of haemophilia and its management. | Haemo-QOL: overall, parents overestimated the impact on the child’s quality of life for 8–12 year-olds but not for children aged 4–7 or 13–16. Other findings were not separately reported for parents. |

| Forsyth et al, 2014 [15] Algeria, Argentina, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK, US | 561 parents recruited via national haemophilia agencies. | Online survey including EuroQol, a modified version of the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index, satisfaction subscale of the Male Sexual Health Questionnaire. | 63% of parents reported that caring for a child with haemophilia had a negative impact on their working life. 29% said they selected their employment taking into account the need to care for their child; 24% worked flexible hours as a result and 14% had to limit their hours. 10% said they had a lost a job due to caring for their child, 9% said it had cost them promotion and 7% believed they had not been offered a job for this reason. The proportion of parents affected varies by country. |

| Wiedebusch et al, 2008 [16] Germany | Parents (n=55 of 160 invited) of children with haemophilia (mean age 11, range 1 – 20) attending a haemophilia centre. Compared with parents of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis or type 1 diabetes. Almost all cases of haemophilia were severe and treated with on-demand FVIII. | Ulm Quality of Life Inventory for Parents | The overall quality of life score was in the ‘average’ range, with no differences between fathers and mothers. The overall score correlated with parents’ subjective perception of the child’s limitation by illness in daily life, but not with duration of illness. Parents of children with haemophilia experienced a higher quality of life than parents of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis or type 1 diabetes. Parents’ quality of life was predicted by improving the marital relationship and having fewer emotional strains and worries concerning the future. |

| Torres-Ortuño et al, 2014 [21] Spain | 49 parents of children with haemophilia (age 1 – 7) attending a workshop. | Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (FACES III), Pediatric Inventory for Parents (PIP; measures parental stress). | Family functioning scored within ‘intermediate range’. Levels of stress were ‘within the average’. Mothers scored higher stress levels than fathers. Use of a portacath helped parents manage treatment better. |

Impaired quality of life was associated with greater reported bother about the child’s haemophilia [9] the parents’ perception of how much their child’s life was limited by the condition [16] and inhibitor status [10,13]. The child’s age may be one influence on the level of parental concern: in one study, parents overestimated the impact of impaired quality of life on their 8 – 12 year-old children, but did not do so for other age groups [14]; in another, more domains of quality of life were affected for parents of 8 – 16 year-olds than for 4 – 7 year-olds.

Reported factors of concern included the child’s pain [9,10], care tasks [10], treatment administration [9], worry about transition arrangements [11] and partner’s distress [11]. Parents were likely to have less time to themselves [10] report a negative impact on their social lives or report impairment in relationships [9]. Family or sibling relationships were also identified as areas of concern [9,13]. Conversely, quality of life scores were likely to be higher for parents who reported trying to improve their marital relationshipand having fewer concerns about the future [16], the latter being a factor underlying parental distress [11].

The financial implications of haemophilia contributed to impaired quality of life [9,10,13], although the studies in which this was reported were carried out partly or entirely in countries with largely private health care systems (US and Canada). The HERO study, which involved participants from ten countries in Europe, North and South America and China, found that almost two-thirds of parents believed their child’s haemophilia had adversely affected their employment, reporting reduced hours or part-time employment, and harmed or lost career opportunities [15]. The proportion of respondents who believed their employment had been affected in this way varied between countries, perhaps reflecting contrasting cultural norms in this diverse group. Diary records kept by caregivers showed that 18% of bleeding episodes resulted in loss of time at work or education [18].

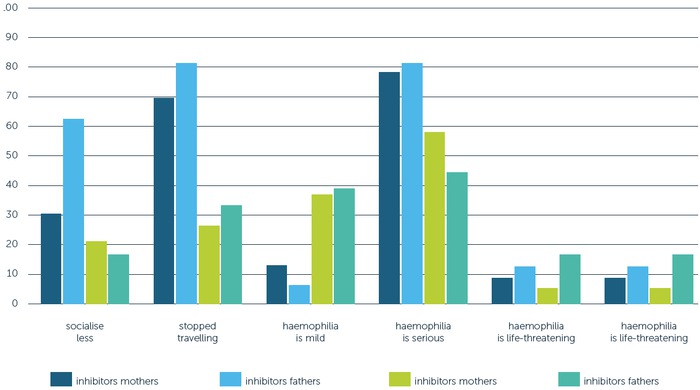

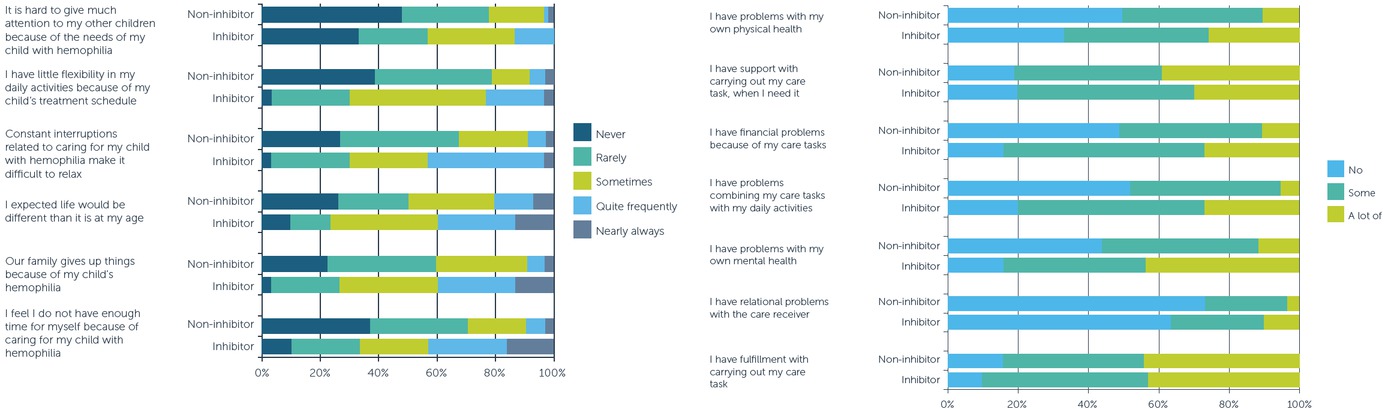

Two studies examined the impact of inhibitors on parental quality of life. One found inhibitors were associated with greater impairment, negatively affecting mental and physical health, causing financial problems because of care tasks and difficulty combining care tasks with daily activities [10]. After adjusting for potential confounders (e.g. caregiver demographics, haemophilia type and time since diagnosis), current inhibitor status positively correlated with caregiver burden. Conversely, caring tasks could also be fulfilling and most respondents reported support from their partners in carrying them out. This particular study – a large online survey conducted in the US – shows how misleading it is to make sweeping statements implying that all parents feel the same way. Parents had a range of views of varying strengths; overall, however, having a child with an inhibitor was associated with more negative views (Figure 1). On a visual analogue scale measuring burden of care (10 = worst), the median score for parents of a child with inhibitors was 5.5, compared with 3.0 for those whose child did not have inhibitors; the corresponding figures for carer quality of life (10 = best) were 5.5 and 7.0 respectively.

Figure 1

Distribution of caregiver burden (left) and Care Quality of Life (right) responses for parents of children with or without inhibitors [10]

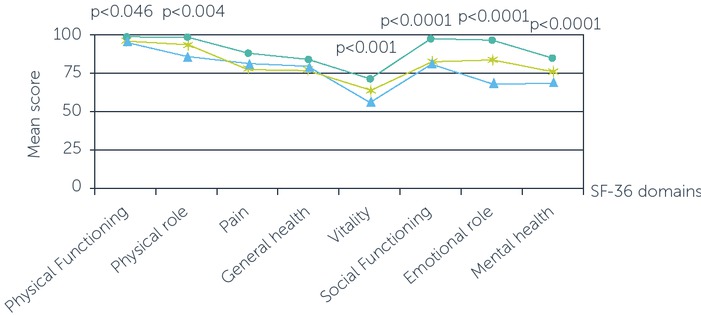

The second study, conducted in Canada, Sweden and the UK, found that haemophilia was associated with worse scores compared with parents of healthy children in most domains of quality of life (Figure 2). There was no difference in overall quality of life score according to inhibitor status, although having inhibitors was associated with significantly greater effects on most domains of the caregiver burden (Figure 3) [13]. In this study, children with inhibitors were more likely to have had bleeding episodes in the previous six months (mean 2.8 vs 0.6 episodes) and had a higher frequency of medical check-ups (mean 6.26 vs 1.78 per year) than children with no inhibitors.

Figure 2

Impact of inhibitors on quality of life domains [13]

Key:[Triangle]: Inhibitor caregivers [Asterisk]: No-inhibitor caregivers [Circle]: Healthy caregivers

Figure 3

Impact of inhibitors of caregiver burden (All comparisons p=0.0001 except emotional involvement (p=0.313)) [13]

Anxiety/depression

Several studies reported worry or stress among parents [2,4,5,9,10,11,18] but few assessed anxiety and depression. In 42 mothers of children with haemophilia aged 7 – 16 recruited from the Haemophilia Society of Turkey [17], anxiety was assessed using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), in which a higher score indicates greater anxiety. Mean state anxiety score was higher than trait anxiety score (mean 44 vs 37) and correlated with the mother’s age. In the Italian online survey, 54% of parents recorded ‘problems’ in the anxiety/depression dimension of the EuroQol quality of life assessment tool and 46% did not; this difference was not statistically significant [12].

Competence, parenting skills, satisfaction/interference with daily living

Parental overprotectiveness was reported among mothers of 7 – 16 year-olds in Turkey [17] and in open-ended questions [15], which is consistent with the finding that parents may overestimate the impact of haemophilia on their child [14]. Another US survey of fathers of boys with

haemophilia (age range 9 months – 18 years) found that worry about spending too little time with their sons and rarely or never administering treatment resulted in lower self-ratings of parenting efficacy [18].

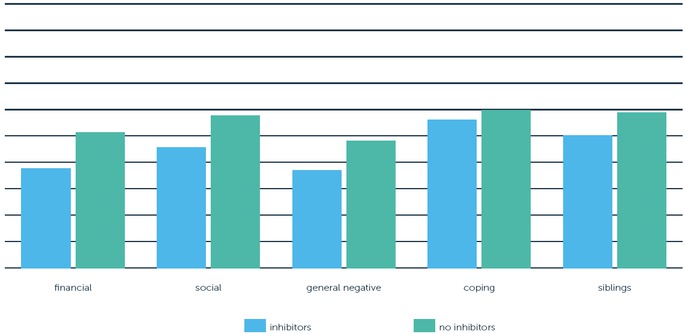

Some caregivers reported that they or their family gave things up for the child with haemophilia, especially if the child had inhibitors [10]. Using the Impact on Family Scale, a US study reported a significantly greater effect on scales measuring financial, social, general negative and siblings for children with inhibitors compared with those with no inhibitors (Figure 4) [13]. Figure 5 shows that parents of children with inhibitors restricted their lifestyle more and were more likely to rate haemophilia as a serious condition; the impact on fathers’ lifestyle was greater than that on mothers.

Figure 4

Impact of inhibitors on family (comparisons: financial, p<0.001; social, p<0.0001; general negative, p<0.001; coping, p<0.177; siblings, p<0.026) [13]

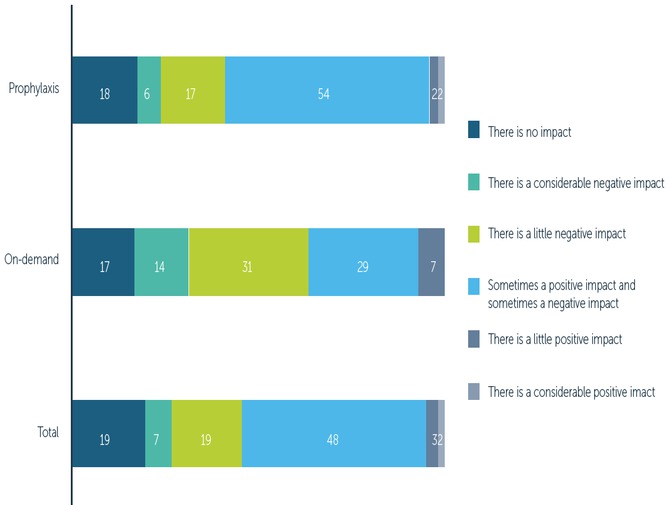

Analysis of diary records revealed that bleeding episodes disrupted activities planned by parents or caregivers on about 40% of affected days, accounting for serious disruption on up to 16% [19]. The extent of interference with family plans increased with the duration of bleeding, with joint and ‘other’ bleeds causing more problems than muscle bleeds. The international HERO study quantified the impact of haemophilia on unaffected siblings (Figure 6); overall, the impact was less frequently negative for those using prophylaxis compared with on-demand treatment [20]. The negative impact was largely due to siblings receiving less time and feeling resentment at the disproportionate time devoted to the child with haemophilia. However, there were also positive effects, with some parents noting that siblings had greater responsibility and maturity, around half indicating their son’s haemophilia made the whole family closer, and 40% reporting their children were closer as a result of their son’s diagnosis. The vast majority of parents were satisfied with the support they received from their partners and family, mainly through communication, trust, love and investment in their son’s care.

A Spanish survey of parents reported levels of family functioning and stress that were average for the population, but concluded they had ‘difficulties in adapting to managing the disease; they perceive many stressors and have problems coping with them, not only with the clinical aspects but also at a psychosocial level’ [21]. This study includes multiple analyses and is difficult to interpret. The authors recommend a multidisciplinary approach that would reduce stress and promote the use of coping strategies.

Summary

Qualitative studies show that being a parent of a child with haemophilia can be challenging, from the time of diagnosis, through adjusting family life and learning to manage treatment. Treatment at home offered empowerment and greater independence from health professionals, but also brought more responsibility. The quality of the relationship between parents and health professionals is an important factor in adjusting to living with a child with haemophilia, and a strong relationship between parents was associated with a higher quality of life.

Parental quality of life is impaired by having a child with haemophilia, with social/personal life curtailed, career opportunities limited and worry or stress being common. The increased burden of care for children with inhibitors can exacerbate these problems. Prophylaxis was associated with better quality of life than on-demand treatment. Parents identified positive effects of home treatment on their children (such as closer family unity and increased maturity) as well as negative ones (e.g. increased treatment burden, lack of confidence with injections).

Interventional studies

These studies describe distinctly different approaches to promoting psychological wellbeing among parents of children with haemophilia.

In Italy, 156 parent pairs aged >30 were recruited to a counselling programme between October 2003 and July 2004 [22]. The programme comprised monthly group meetings under the supervision of a psychologist, each with a different theme. The group was encouraged to share their concerns and difficulties, and to jointly develop adaptive processes of problem-solving and decision-making. Participants were assessed at the beginning and end of the programme using the COPE questionnaire (to evaluate coping strategies), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to assess state-anxiety. By the end of the programme, there was a small increase in the use of coping strategies that were emotion-focused, a larger increase in those that were problem-focused and no change in avoidance strategies. Scores of depression and state-anxiety were significantly improved. These changes were not associated with age, level of education or profession, but there were differences between mothers and fathers: the use of problem-focused strategies increased more and that of emotion-focused strategies decreased less in mothers. In addition, scores of depression and anxiety were slightly higher among mothers at baseline and this difference remained after the programme. The authors comment that problem-focused strategies are adaptive behaviours in stressful situations. They also noted that mothers were more likely to contribute to group discussions than fathers, who seemed disinterested. This suggests the need for different approaches to providing support to mothers and fathers.

Researchers in South Korea described a pilot study self-help group involving 12 mothers of children with haemophilia aged 3 – 14 [23]. Meetings were held twice-weekly for five weeks. The meeting content was developed from literature reviews, a survey of caregivers and experience of a support group for people with haemophilia. The aim was to improve knowledge about haemophilia and its management, to improve parenting ability and self-efficacy, and to encourage self-care among mothers. In addition, physical therapy and strength training was offered to help with the physical aspects of caring. Knowledge was measured by questionnaire, depression by a face numerical scale, rearing stress by the Parent Stress Index, and quality of life and self-efficacy by published tools.

Compared with baseline, scores of knowledge, self-efficacy and quality of life were significantly improved after the programme; scores for depression were significantly reduced (it is not clear how severe depression was at baseline). There was no statistically significant change in rearing stress. Participants were satisfied (33%) or very satisfied (67%) with the programme, rating its main positive aspects as obtaining accurate knowledge and extensive information (67%), having confidence (33%), meeting mothers in the same situation (33%) and experiencing different activities (17%). Most wanted more time to discuss topics in greater depth and 42% requested a programme for the whole family.

Education about haemophilia, its management and the physical aspects of the condition was shown to reduce stress among 22 mothers of children with haemophilia aged under 4 [24]. This non-randomised Spanish study assigned mothers to participate in an educational programme delivered by a physiotherapist or a control group who received usual care. The programme used materials developed by the World Federation of Hemophilia (www.wfh.org) to increase knowledge about the pathophysiology of haemophilia, living with the condition and its musculoskeletal effects. This was delivered in two 2.5 hour sessions, one month apart. Quality of life was assessed using SF-36, anxiety by STAI, family adaptability and cohesion by FACES III, and perceived stress by the Paediatric Inventory for Parents.

Compared with baseline, participants in the intervention group had significant improvements in perceived family functioning, measures of coping with stress and perceived family cohesion. The mean trait anxiety score improved in the control group. There was no significant change in quality of life scores in the intervention group, whereas the domain of physical functioning improved in controls. Multiple comparisons identified statistically significant correlations at baseline between haemophilia severity and its treatment and family functioning, anxiety and stress. After the intervention, some of these correlations were no longer statistically significant. Cohesion and family functioning improved, but family stress worsened slightly among mothers in the intervention group; stress was reduced among fathers. There were no corresponding changes in the control group.

Summary

These intervention studies show that different strategies to support parents have a positive effect on the psychosocial aspects of caring for a child with haemophilia. The programmes differ in their duration and manner of delivery, raising the possibility that adapting the format of a programme to local needs may not diminish its success. None of the studies were randomised, two were not controlled and two were small. The risk of bias cannot be excluded, but the practical difficulties of conducting research of this nature should be acknowledged.

Discussion

This review shows that raising a child with haemophilia can be challenging for parents and the family, with impacts on all aspects of life and heightened or excessive concern for the child’s well-being. The process of coming to terms with the diagnosis, learning to manage treatment and integrating the child’s care needs into everyday life is not easy – parental descriptions are of stress and effort rather than having achieved control. Employment and career prospects suffered: parents said they selected their job with their child’s needs in mind or modified their hours to provide care. Parents had to be assertive in their dealings with health professionals to get what they believed was the best for their child. They rated their quality of life lower than parents of healthy children did, although not as low as parents of children with other life-long conditions associated with pain (juvenile idiopathic arthritis) or injected treatment (type 1 diabetes). Worry was often reported, but there was little assessment of anxiety and depression.

The advent of prophylaxis reduced the burden associated with hospital visits and the uncertainty and disruption from frequent bleeding episodes, but increased parental responsibility for the child’s care. Parents did not find it easy to inject their children and the child’s reaction to treatment influenced their ability to cope. Home-based prophylaxis and the use of a CVAD posed practical difficulties, but also offered independence and empowerment. A positive relationship with health professionals was helpful in coming to terms with treatment. Some parents said that living with haemophilia was incompatible with a normal life; others that life was not what they expected. The development of inhibitors makes these issues worse or more frequent by increasing the caregiver burden and the impact on the family, but the picture is not uniformly gloomy. Not all parents expressed negative views; some found that caring for their child was fulfilling, partners were supportive and family bonds were strengthened; and some parents were not affected by the presence of inhibitors.

Knowledge about haemophilia and its treatment was clearly valued by parents, with some identifying it as the key to mastering management. Intervention studies show that programmes that increase knowledge among mothers were welcomed and had important effects on participants’ mood, stress management and functioning. Families interpreted academic information provided by health professionals in a way that was meaningful to them, highlighting the importance of tailoring information to individual needs. Support from family, friends and health professionals was clearly invaluable in helping parents adjust and cope with a new life of providing care.

Several studies surveyed parents in different countries. Contrasting health care systems and cultural differences might limit the extent to which the findings can be applied locally: the HERO study included Algeria, the US and China, for example [15], and there are probably important differences even between Sweden, the UK and Canada [13]. However, experience from Turkey, where many mothers in one survey had little education and showed a high level of need for support [8], is instructive for any country with communities where there are disadvantaged families.

Conclusion

This literature review describes many common themes from observational studies that were generally consistent with those emerging from interviews of parents of children with haemophilia. Few intervention studies were identified. Overall, this evidence shows that quality of life is impaired in the parents of a child with haemophilia and that many aspects of life are affected. However, providing care can also be rewarding and programmes of support, education and appropriate treatment evidently improve the well-being of parents and families.