This study explored whether the source of factor VIII (FVIII) replacement affects the rate of inhibitory antibodies in previous untreated patients (PUPs) with severe hemophilia A. SIPPET is an international, multicentre, prospective, controlled, randomised and open-label clinical study that aimed to test the hypothesis that plasma-derived VWF/FVIII (pdFVII) products are less immunogenic than recombinant FVIII (rFVIII) products [1]. The study compared two classes of products and not two specific products belonging to these classes. The study therefore assumed that all FVIII products are equally efficacious and broadly equivalent with respect to their capacity to control bleeding.

SIPPET was conducted between January 2010 and December 2014 at 42 sites in 14 countries on five continents. It included 251 children <6 years of age with severe haemophilia A. After randomization 125 patients received pdFVIII and 126 rFVIII. In all, 76 patients developed an inhibitor, of which 50 were high-titre inhibitors. The cumulative inhibitor incidence was 35.4% (95% confidence interval [CI 95] 28.9-41.9%). 90% of inhibitors developed within 20 exposure days, both for all and high-titre inhibitors. The putative confounders were equally divided between the two product class arms. There were 29 inhibitors (20 high-titre) in the group treated with the class of pdFVIII and 47 (30 high-titre) in those treated with rFVIII. The cumulative inhibitor incidence was 26.7% (CI 95 18.335.1%) for pdFVIII and 44.5% (CI 95 34.7-54.3%) for rFVIII. For high-titre inhibitors the cumulative incidence was 18.5% (CI 95 12.1-26.9%) for pdFVIII and 28.4% (CI 95 19.6-37.2%) for rFVIII.

The SIPPET study results reflected an 87% higher incidence of inhibitor formation in toddler-aged hemophilia patients receiving recombinant factor VIII concentrates than in toddlers receiving plasma-derived factor VIII concentrates.

In other words, patients treated with a rFVIII were nearly twice as likely to develop an inhibitor than their peers treated with a pdFVIII. This difference remained even when second-generation full length rFVIII concentrates were excluded from the analyses.

The SIPPET trial provides strong evidence that, in patients with severe haemophilia A, rFVIII increases the risk of developing high-titre inhibitors as compared with pdFVIII. The number needed to harm, calculated from these data, was 10. In other words, for every 10 patients who are treated with rFVIII as opposed to pdFVIII, one patient is expected to develop a high-titre inhibitor.

Now that the study has been completed and the results released – at least as an abstract – the next step is to try to understand what this information means and to consider the implications for the haemophilia community. The information available indeed raises several important unanswered questions and critical issues.

Will the results and conclusions of the SIPPET study be accepted by the haemophilia community? Even if SIPPET is the largest randomised controlled trial testing the influence of the source of FVIII product on inhibitor development, evidence remains to be fully provided that there was no difference at all between both arms. At present, no full publication is yet available, and we cannot rule out the possibility that some methodological biases and potential confounders will emerge, be identified or suspected and impact negatively on the validity of the study. As the study involved many patients from Africa or India, it is very likely that some treaters will question its applicability to their own patient populations with a different ethnic background.

At this stage we cannot assume that the SIPPET study will definitely close the long-lasting and passionate debate about the risk of inhibitor with pdFVIII versus rFVIII. The conclusions of the SIPPET study are indeed at odds with those of the well-known RODIN study, which did not report a significant difference between the two classes of FVIII concentrates [2].

Since the release of the results of SIPPT, there has been no statement regarding the study results and their implications from the numerous active patients and health professionals associations at national or global levels as well by regulatory agencies. It will be of major relevance and interest to see how these important bodies react and comment on the SIPPET study. It is likely that these bodies willl have started to discuss and deliberate but will wait until publication of the final results before communicating more widely, cautiously and explicitly.

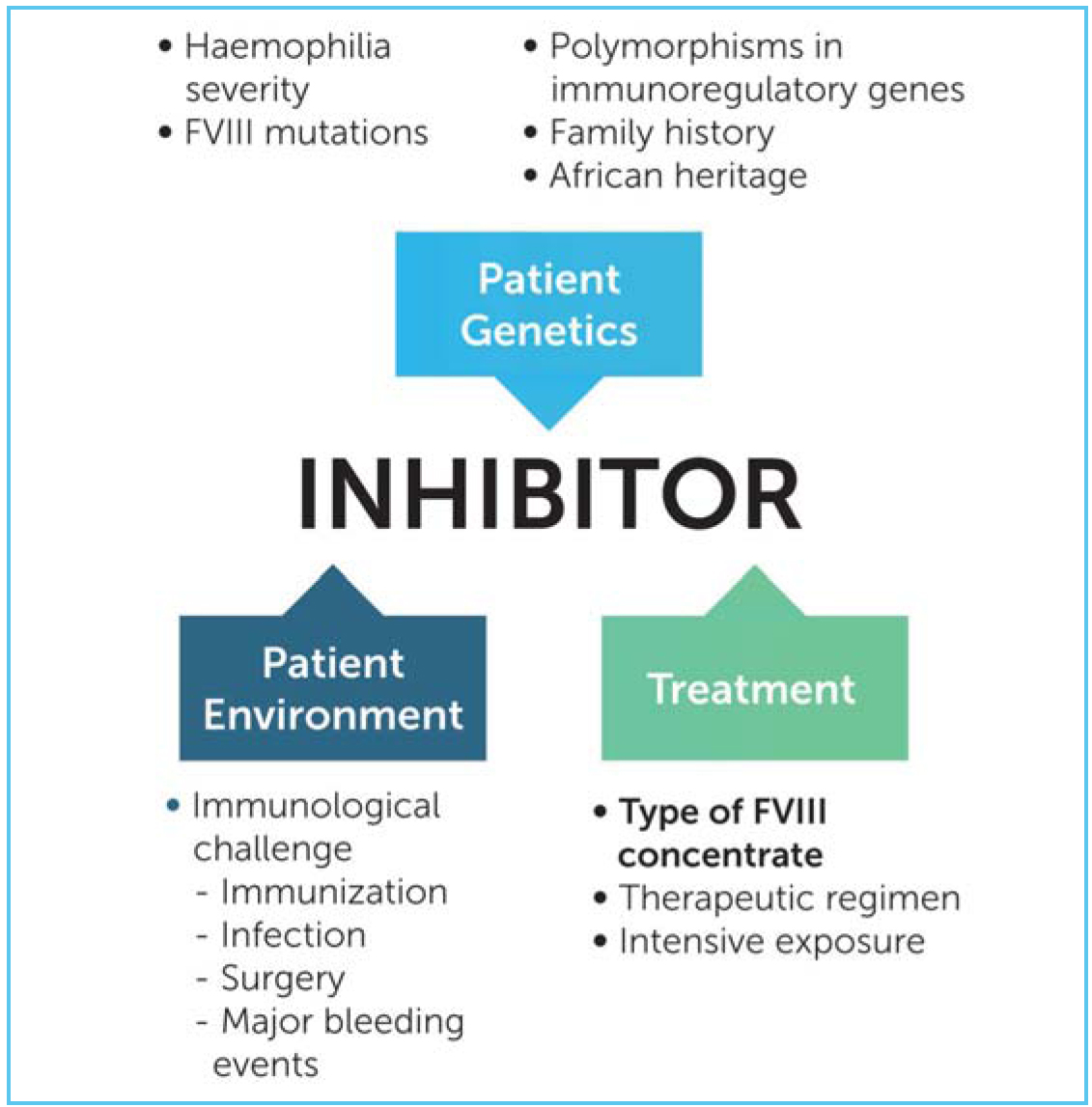

SIPPET clearly found a markedly reduced rate of inhibitor development in patients treated with plasma-derived products. However, patients treated with pdFVIII are still at risk of developing inhibitor. The potential benefits of pdFVIII to induce tolerance to exogenous FVIII should not be overestimated in the future. The development of inhibitor is indeed mysterious in many patients and several major drivers have been identified and extensively validated such as the genotype, family history, presence of polymorphisms of some immuno-regulatory genes as well as the intensive exposure to FVIII at early age. Clearly, the source of the concentrate represents only one piece of a complex puzzle but an important piece that can be modified and on which interventions are possible.

At this stage, it is difficult to appreciate what the impact will be on the management of PUPs with severe haemophilia A. Should all new PUPs now be treated with pdFVIII? This would represent a major change in practice in many countries that have largely adopted rFVIII. Adoption and use of pdFVIII will probably be heterogenous, showing marked variability between countries and centres and will be influenced by several objective and subjective factors such as acceptance and confidence of pdFVIII, availability and level of infectious safety of pdFVIII concentrates. The pdFVIII products are indeed very heterogenous with respect to manufacturing processes, content and level of infectious safety. At the present time, some countries have largely if not exclusively promoted the use of rFVIII because of the past history of major infections and the persistent lack of trust in the infectious safety of pdFVIII, mainly with respect to some potential emerging infectious agents. In some countries, by contrast, the risk of inhibitor development is perceived as a major threat and the use of pdFVIII presently considered as a better approach to minimise it.

One should also be well aware that the conclusions of the SIPPET study only apply to PUPs (a few patients per year in small countries) and have no implications at all for the vast majority of patients with severe haemophilia A currently treated with rFVIII. For these patients, their treatment should not be modified. This is a very important message that should be delivered to the patients and the general public in order to avoid confusion, fear, loss of confidence, inappropriate interruptions or switches in current treatments. Also, since SIPPET did not provide a product specific comparison, no particular product should be taken off the market.

The results of the SIPPET study could also have major implications on the validation of new rFVIII products in PUPs. One could indeed question whether it would still be ethically valid to treat PUPs with rFVIII in the future. At the same time, the SIPPET conclusions should not compromise the further development of new concentrates in PUPs, which could have several valuable advantages.

Although the SIPPET study only involved PUPs with severe HA, one could assume that the same conclusions could to some extent be applied to older patients with mild or moderate HA and with limited pervious exposure to FVIII concentrates, especially if these patients carry a high risk mutation for inhibitor development.

Anticipated reduction of the risk of inhibitor development with wider use of pdFVIII would have many financial implications that should also be carefully taken into account. From an economic point of view and applying the conclusions of SIPPET, the use of rFVIII could be associated with an average increase in the treatment cost per patient equal to the average cost of treating one case of a high titre inhibitor divided by 10 [3]. This in turn raises the need to estimate the average cost to treat one patient who develops a high-titre inhibitor. One cannot foresee how health authorities and payers will analyse the results of the SIPPET study and how these results will impact on concentrates price and prescription criteria in some countries. It is however very likely that based on the results of the SIPPET study, pdFVIII should be preferred for patients living in countries where immuno-tolerance therapy and bypassing agents are not readily or widely available. This is the case for most developing countries, where SIPPET could have major implications on the choice of concentrate.

The SIPPET study should certainly prompt new research in order to try to better understand the reasons for the difference in immunogenicity between pdFVIII and rFVIII. Several explanations have already been proposed, such as the production of rFVIII by mammalian cell lines vs native FVIII from human plasma, post-translational modifications of rFVIII, high VWF content in pdFVIII products resulting in epitope masking and protection from endocytosis, immunomodulatory human proteins in pdFVIII. The respective importance of each of these factors should be further explored.

It also remains to be seen whether differences observed between pdFVIII and rFVIII can be extrapolated to new short or longer acting rFVIII produced by human cell lines. Indeed, production of concentrates by human cell lines, modifications such as pegylation and fusion to other proteins such as the Fc fragment of immunoglobulins could all modify and reduce the immunogenicity of concentrates. None of the patients enrolled in the SIPPET study was treated with one of these innovative recombinant products which could be less immunogenic.

Development of an inhibitor is currently the major complication of replacement therapy of haemophilia A. The results of the SIPPET study will probably have major implications not only on the management of haemophilia A in PUPs but also more globally on the current and future replacement therapy of patients with haemophilia A. The next few months will show us how the whole haemophilia community reacts to these critical new data.