The deficiency of clotting factors in haemophilia can result in internal bleeding into joints and muscles. Bleeds into a joint can severely reduce the joint function and mobility, resulting in haemophilic arthropathy, disability and impact on an individual’s quality of life [1].

Haemophilia is classified as mild, moderate or severe, the severity being proportional to the level of clotting factor present and broadly equating to the clinical severity experienced by the individual [2]. Mild haemophilia is diagnosed if the patient has 5-40% of normal clotting factor. Mild haemophilia patients tend only to bleed following trauma, surgery, invasive procedures or dental extraction, with some individuals reporting never having experienced any bleeding episodes [3]. However, mild haemophilia patients can experience the same pain and long-term disabilities more commonly associated with severe haemophilia [4]. A single bleed can lead to permanent joint damage, therefore prompt treatment is important [5]. Ideally, treatment should commence as soon as possible after a bleed occurs, or within two hours.

Patients with mild haemophilia are not usually taught how to self-infuse factor at home, and are generally treated either at a haemophilia centre or their local hospital Accident and Emergency (A&E) department [4]. Our haemophilia team observed that, after the onset of a bleeding episode, mild haemophilia patients tended to delay accessing healthcare, an observation consistent with reported experiences in Italy, Canada, and Scandinavia [6, 7, 8]. Most haemophilia research has focused on those with severe haemophilia: there are very few studies looking at the needs of those with mild haemophilia. Due to the differences in bleed patterns, their experience may differ from those with severe disease [9].

A literature search of Ovid MEDLINE 1946 to June week 3 2014 and EMBASE 1980 to 2014 week 26 found only two studies that focused exclusively on the experience and management of mild haemophilia patients [7, 10]. Nilson et al. conducted semi-structured interviews with 18 patients with mild haemophilia [7]. Four major common themes were identified: the reluctance of some individuals to acknowledge their diagnosis of mild haemophilia; the importance that was placed on experiential learning; negative reception of advice from health care teams; and a strategy with a possible bleed to watch and wait before accessing health care. Some individuals perceived the information they received as being more focused on those with severe haemophilia, which led to a resistance in accepting any medical advice. Some, if they had not had a recent bleed, opted not to attend routine clinic reviews, believing that they would not receive any new information.

Walsh et al conducted a two-year quantitative study within a rural population, involving 80 participants: 47 with haemophilia A and 33 unaffected controls [10]. The haemophilia group had a significantly lower standard of general health and more emotional problems than the control group.

In order to gain insight into the experience of living with mild haemophilia and to identify areas within the service that could be improved, this research aimed to explore how bleeding episodes impacted on quality of life, and when and why people with mild haemophilia access healthcare.

Methods

The Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland granted ethical approval (Ref. No. 13/NI/0215) for the study.

The study aimed to explore the experience of haemophilia patients living with mild haemophilia and accessing healthcare when experiencing episodes of bleeding. To reveal these experiences, a semi-structured interview design was adopted for use with eligible participants from two London-based haemophilia centres. All adults registered with a diagnosis of mild haemophilia were eligible for the study. On behalf of the main researcher, the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) from the two haemophilia centres accessed the UK National Haemophilia Database (NHD) and potential participants’ notes to assess the possible eligibility of individuals. In the first instance 12 potential participants were identified; this allowed for non-responders, previous research having identified the possibility of a low response rate [7]. Purposeful selection was used to ensure a range of ages, and an equal number of participants were selected for enrolment from both sites. Using this method raised the possibility of selection bias, as the CNS from each of the haemophilia centres involved may have been influenced by their prior knowledge of the individuals.

Having identified potentially eligible participants, the CNS at each centre asked permission for contact details to be passed onto the main researcher, who then invited them to participate in the research. The CNS also sent the eligible participants a covering letter, information sheet, consent form and prepaid envelope. The researcher then purposefully identified 12 patients across an age range of 26-83 to contribute to the study, with equal numbers from both centres. Eight of the 12 volunteered to be interviewed.

In order to obtain a fresh perspective and not allow the researchers’ prior knowledge to influence the results, Husserl’s descriptive phenomenology methodology was used [11]. In order to rule out the influence of preconceptions on the research, no intended outcomes were identified and no hypothesis was proposed [12]. Prior to the interviews being conducted, the researcher acknowledged and listed all prior assumptions and beliefs and attempted to “bracket them out” or put them to one side [13].

To prevent any bias occurring as a result of the patient-nurse relationship, participants were interviewed by a nurse not known to them. Following written informed consent, the nurse explained the use of an audio recorder and the confidentiality of any personal information. Individual semi-structured interviews using open-ended questions were employed. The interviews were conducted in a quiet counselling room and commenced with open questions, such as:

Can you explain how you feel about having a diagnosis of mild haemophilia?

Having had a bleed, can you describe, in as much detail as you can, what the experience was like for you when you accessed health care?

Subsequent questions depended on what was revealed in the participant’s response to the first group of questions. Probing style questions were used for clarification and to gain more in-depth descriptions [14].

Transcripts, as well as a summary of the findings, were returned to the participants to further ensure accuracy; no comments or alternations were requested. Data were anonymised in order to maintain the confidentiality of the participants; each participant was allocated a fictitious name. The interviews were professionally transcribed, verbatim, and analysed based on an adapted version of the Colaizzi seven step method [15].

Results

Eight participants, age range 26-83 years (median 52), were interviewed; seven had mild haemophilia A and one had mild haemophilia B (Table 1). Participants were initially allocated a number between P001-P008. Having completed this process, to ensure anonymity and for ease of reading, each P number was allocated a fictitious name (Table 2).

Table1.

Age of participants and haemophilia type

| Age | Haemophilia type |

|---|---|

| 26,37,40,46, 68,70,80 | Haemophilia A |

| 58 | Haemophilia B |

Table 2.

Participant codes and pseudonyms

| Participant number | Code | Pseudonym |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | P001 | Jack |

| 2 | P002 | Stan |

| 3 | P003 | Gus |

| 4 | P004 | Lee |

| 5 | P005 | Duncan |

| 6 | P006 | Julian |

| 7 | P007 | Matthew |

| 8 | P008 | Luke |

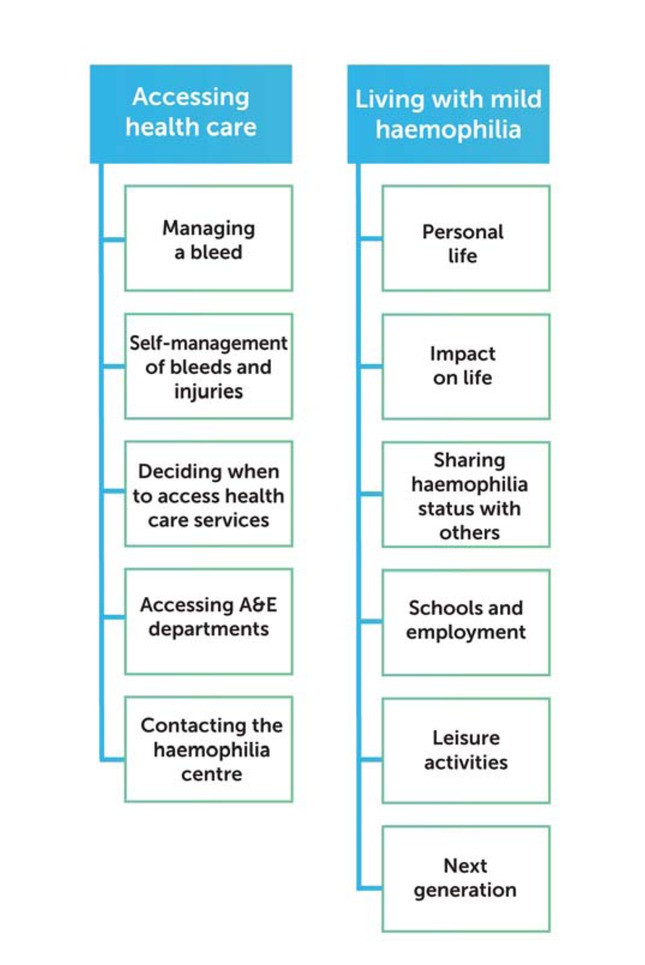

Analysis revealed two main themes: accessing health care and living with mild haemophilia, each divided into sub-themes (Figure 1). Verbatim quotes are given in italics to illustrate themes.

Accessing health care

A.

Managing a bleed

Two participants were unaware that their bleeding episodes lasted any longer than the average person: “I didn’t think that I bled any more than anyone else… I thought I healed pretty quickly. But apparently I didn’t.” (Jack).

Others felt that it could be irritating or annoying, but did not seem very concerned: “You realise that, when you get hurt, you know that it might take a bit longer than usual.” (Julian)

Participants who had a good response to DDAVP s/c and had never received clotting replacement factors were pleased: “I’ve never had any factor in my life. I just have DDAVP (s/c); they say I have a very good response to that. The less I have to have factor, the better, really.” (Gus).

Self-management of bleeds and injuries

When experiencing a small bleed or cut, seven of the participants knew and followed the standard RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevate) principle: “I tried to manage small bleeds at home. Ice, elevate, compression, rest.” (Luke).

Two of the participants had taken aspirin or ibuprofen for pain relief which, unbeknown to them at the time, is contraindicated for people with haemophilia: “My calf swelled up, I took tons of [ibuprofen]… I now know, but it was just I didn’t - well, nobody told me.” (Stan).

Overall, they all felt that they could manage small bleeds at home and explained that they would wait and see before seeking further help and advice: “Sometimes the process of travelling from home to the centre and getting it looked at and being on your feet all that time, that can actually be a strain on the bleed. I know instantly if it’s, you know, something serious, if it’s more serious than that, because it’s more painful.” (Matthew).

Deciding when to access health care

The severity of the pain experienced by the participants was used as a general guide to gauge whether they needed to seek further advice or treatment. Unfortunately, this has not always been an accurate barometer: “I thought it was a bleed, but I didn’t realise I’d broken my leg.” (Lee).

Accurately assessing the severity of a bleed or injury that was different from the type of bleeds that they usually experienced was challenging for participants: “Instead of a normal bleed, the bleed was in the muscle. So it was a completely different feeling; it felt a little bit more like a constant dead leg. So yes, I delayed going and getting the treatment for that, because in my head I thought, ‘Oh that’s something different, that’s not a bleed.’” (Matthew).

Participants generally knew when they were having a bleed. However, for some, bruises didn’t count as a bleed: “it caused a massive bruise. I didn’t treat it, as I thought that’s just a bruise, you know.” (Julian).

For small bleeds or injuries, all participants would wait and see if it improved for at least 24 hours before accessing health care. However, if they assessed the bleed to be more significant, they would attend for treatment: “I used to tend to wait and see. But I found out that didn’t really work! In the end you’ve got to, you know, go. So now I am normally pretty sensible and get myself up here if it’s a hard bang. I don’t wait.” (Duncan)

Internal bleeds are the most worrying, as this is difficult to assess: “If I can see the blood coming out, I can find a way of stopping it. What frightens me is what goes on inside, and you can’t tell if there’s a bleed inside.” (Luke).

Participants who had medication at home would self-administer before seeking medical advice: “I keep a stock of factor at home. And if I get a bleed or I suspect I’ve got a bleed, I give myself an injection straight away ... That’s always been the philosophy that they’ve always instilled in me. If in doubt, inject.” (Lee).

Accessing A&E departments

Attending an Accident and Emergency (A&E) department as a child did not appear to have caused negative feelings in the past: “I remember jokes as I’d go into A&E or the hospital, ‘Oh, hello. What have you done this week?’ So I was in quite often.” (Matthew).

However, as adults, attending an A&E department following an injury evoked strong resistance from all participants: “I did it on Friday lunchtime at work… I decided to attend A&E on Sunday morning, because I thought I’d go at 8am because that’s when there a changeover… On the basis that this is when I think is the least busy time.” (Stan).

The perceived time that would be spent waiting in the A&E department was a real concern for all participants: “I’ve always had a bad experience with A&E... because they will keep you there forever.” (Julian).

On one occasion, the aversion of one of the participants to waiting for a long time in A&E prevented him informing staff that he had haemophilia: “I never told them I was haemophiliac. I knew it would be extra this, that and the other… And I couldn’t... I realise I should have told them.” (Duncan)

Although participants assumed there would be long waits in A&E departments, this was not always the case. Two participants acknowledged that, when they did attend, they were seen straight away: “Following on from an injury, I went to A&E and the nurse said ‘I don’t want you bleeding all over my floor, we’d better see you first.’” (Jack).

If participants had to attend an A&E department, they preferred to attend at the same hospital site as their own haemophilia centre, as they were more confident that they would be seen by someone that knew about haemophilia: “Ideally the same A&E for the centre, as if for any reason I needed to be admitted, then I’m in the right place… I went to one hospital and they spent quite a lot of time panicking because I said I was a haemophiliac - and a long time trying to find an available haematologist. And the haematologist had never treated a haemophiliac before.” (Matthew).

All participants stated that they had been issued with a medical diagnostic card, which includes their name, diagnosis, treatment regime and contact details of their haemophilia centre. All participants are asked by their haemophilia team to ensure that they carry their card with them at all times and to present it when accessing health care. One participant did not carry his card with him, as he believed that staff in A&E should be able to access their medical notes instead: “I don’t carry a card with me. If I go to A&E, they will just check my records and they’ll find out I’ve got haemophilia.” (Julian).

Others were less confident that A&E staff would be able to access their medical notes, depending on where they attended: “Going to a minor hospital or your local hospital and trying to get access to documents, you know, all that, it just seems easier for me to drive in here.” (Gus).

Apprehension that they would not be able to get medication in a timely manner was a concern for some of the participants: “They’re just not going to get the factor unless you are dying or something. So they will tell me the exact same thing that I know and would just send me home and say, ‘Come back in the morning.’ So… what’s the point? I prefer to come to the haemophilia centre.” (Julian).

Outside of the haemophilia centre’s normal working hours, there was a notion that even if participants did attend A&E and waited, they would be referred back to the haemophilia centre when it opened: “Waiting for them to decide, you know, and do whatever. And they maybe send me here, so I’d rather just come straight here really.” (Gus).

Although participants were very reluctant to attend their own local hospital A&E, they were more willing to attend if they had contacted their haemophilia centre beforehand: “I generally come here to the centre. If the clinic is closed, there is always someone you can get hold of. I cannot say how grateful I am for that… Then we would meet and they either treat me in A&E here or they would come down here and do it.” (Luke).

Rather than attending A&E following a bleed, all participants preferred to attend their own centre, even if that meant delaying seeking help until the next day: “You turn up and you’ll be treated or suggested what to do, you know, if no treatment is needed. In here you’re a bit privileged. In here you get the better treatment than you get in A&E.” (Julian).

Contacting the haemophilia centre

Having decided to seek medical advice, participants either telephoned their haemophilia centre or just showed up: “I’d ring the centre… I would actually get myself to the centre quite quickly to get it treated.” (Duncan).

All participants believed that, following a bleed or injury, they would get advice from their haemophilia centre as to whether they needed to attend or not: “I could always get her on the phone, she’s always good like that, and if I feel I need any more, she will say either, ‘Give yourself some more,’ or, ‘Come back up and let’s see you.’ It usually is, ‘Come up and see us.’ If you get it early enough, you can stop it.” (Lee).

Attending the haemophilia centre was not always the easier option. Nevertheless, this was everyone’s preferred choice: “It’s a bit of a hassle, but it’s not as much hassle as sitting in an A&E.” (Gus).

All participants rated the service and care that they received at their haemophilia centre as excellent. They felt at ease and very confident with their own haemophilia medical teams: “I can’t fault the service. The service I get from them is very, very good. I can ring up anytime. They always drop everything and come up and see us and, you know, they’re always very good, I can’t fault them.” (Lee).

Whilst they may have experienced difficulties throughout their lives with haemophilia, all participants had an overwhelming appreciation of their clinical teams and the service they received from their haemophilia centres: “I do feel it’s a very good service, actually... we do get a good service.” (Gus).

Regardless of whether it was a haemophilia-related issue or not, participants felt very confident that their haemophilia team would help them: “If I have an issue with something, the first people I talk to would be the team here. And then they would guide me to the right people to get the right treatment.” (Luke).

Living with mild haemophilia

B.

Personal life

The age at which participants recalled first knowing they had a diagnosis of mild haemophilia varied considerably. Two participants had always known, as there was a history of haemophilia in their family. One participant knew as a young child. Three participants were aware of their diagnosis between the ages of 10 and 20: “Only when I had an injury and the bleeding wouldn’t stop, they decided to do a blood test, and within hours, literally, they discovered haemophilia.” (Luke).

The remaining two participants were adults when they discovered that they had haemophilia. Although both sets of parents were fully aware that their child had haemophilia, they chose not share this information: “It’s the strangest thing finding out that I had haemophilia... to get to middle age and then someone said yes, you’ve got this, and yes, you know, it’s… That’s a bit hard to understand, why you weren’t told previously… Other members of the family did know, but I didn’t for some reason.” (Jack).

Discovering they had mild haemophilia was triggered in a variety of ways. Three participants had surgical procedures and diagnosis was made due to bleeding. Two participants attended hospital following an injury and a blood test revealed that they had haemophilia. Two always knew that they had haemophilia. One participant found out by chance.

Impact on life

The majority of participants tried not to let having haemophilia affect their life or the choices they made: “Never stopped me doing anything significantly. I think it’s partly due my own stubbornness. I never let it stop me doing anything.” (Matthew).

Others felt that it had impacted upon their lives: “I’ve had it all my life; I’ve been brought up with it, lived with it. It’s restricted my life, definitely. But it’s much better now.” (Lee).

Participants recognised that it was difficult for parents bringing up a child with haemophilia, but they were appreciative of their parents’ outlook: “My mum and dad were pretty determined to let me lead a normal life. And they did. I was very pleased that they did. I’ve always had the attitude that you pick yourself up and dust yourself down and just start all over again.” (Duncan).

A shared attitude about living with haemophilia was to avoid focusing on it and not to allow it to interfere with their lives: “At the moment it’s nothing unless something happens. So I don’t feel any reason not to do anything in particular. But I’m intrinsically cautious.” (Stan). “We just forget we’ve got it, to a point, until something happens, you know, when we get an injury.” (Julian).

As they got older, their attitudes and behaviours have adapted to living with haemophilia: “I’m a bit more cautious now… I’ve chilled out since then. I had to.” (Luke).

Sharing haemophilia status with others

Whilst participants adapted and learned to live within the limitations of their disorder, other peoples’ attitudes could be irritating: “I do get a bit annoyed when they say, ‘Oh, you’re only mild.’ ... You try being mild... I find that those words do get up my nose.” (Duncan).

Some participants felt that telling their friends and family they had haemophilia was not an issue for them, and believed that this made them feel supported: “My work colleagues know about it and my wife obviously knows about it, and my friends know about it. So if anything should happen, then I feel I’m fairly well covered, that they would know that they would need to alert the clinical team to say that.” (Gus). Others thought that, unless it came up in conversation, it was not something that they would necessarily share with other people: “I often forget I have it significantly, until it comes up in conversation and then people say, ‘Oh, why did you never tell me?’ It’s mostly because I get used to not thinking about it.” (Matthew).

Other participants were more reticent about sharing such personal information with colleagues: “Well, it’s just so something, like, personal, which is sometimes good, but sometimes it’s bad... I just didn’t think I should tell them, you know. So none of them know.” (Julian).

Schools and employment

Five participants felt that haemophilia had restricted what school they could attend or jobs they could do, and found the attitudes they encountered frustrating and annoying: “I grew up not really noticing, until my parents tried to get me into school. I had a minor accident and then my parents had to let the school know that I had haemophilia. So the school said they couldn’t take responsibility for me. So my parents had to search for a school for physically handicapped children. It was a good environment. But I felt like a fish out of water, I felt like I didn’t really belong, because I felt normal all the time. I wanted to go to grammar school, but I was knocked back. I was upset. I got a job, but fell over... and I told them I had haemophilia, so they dismissed me. They got rid of me.” (Duncan).

Most felt, in adulthood, that there was more understanding in the workplace with regards to having haemophilia: “My boss, she understands, it’s not an issue.” (Matthew).

Leisure activities

All participants took part in wide variety of sporting activities, including: athletics, cycling, cricket, football, gym, running, rugby, skiing, snowboarding, swimming and tennis. Participants who were aware of haemophilia when growing up were discouraged from taking part in sport, which they found wearisome and exasperating: “‘Oh, you’re a haemophiliac,’ and, say, sport at school, they’d say ‘Oh, in that case, we’ll teach you how to do refereeing.’ I didn’t want to be excluded... I was too active. I wanted to be involved. And I never let it stop me doing anything.” (Matthew).

Participants were determined not to let having haemophilia impede their quality of life: “I was often getting told off by my GP, when I went to see her with swollen knees. She used to go mad, actually: ‘What the hell do you think I’m going to do about it?’... But I carried on playing… I don’t think it affected my sporting activities, I never let it.” (Duncan).

Some participants resented being told that they couldn’t do certain activities. However, six of them, over time, made their own decisions to avoid or give up some of their sporting activities, mainly due to sustaining an injury: “I’ve just stopped doing contact sport because it’s not worth another visit. Also, it’s my age.” (Stan).

Those who found out about having haemophilia in adulthood did not curtail their sporting activities: “Because I went for so long not knowing... so I thought to myself, ‘Well, if I’ve got this far without, you know, worrying too much, just carry on.’” (Jack). “I never knew I had it. And so it didn’t stop me doing anything, so I didn’t see why it would stop me doing anything going forward. But it just made me a bit more sensible... made me a bit more cautious if anything happened.” (Stan).

Next generation

Haemophilia is an X-linked recessive disorder; meaning that participants’ daughters would be haemophilia carriers, but their sons would be unaffected. When thinking about having children, participants were aware that their daughters may be carriers and that there was a possibility their grandchildren could have haemophilia. This did not influence some participants’ decisions to have children: “Do not see that it is something that I have to worry about, due to all the treatments that people get these days.” (Julian).

Although not all participants knew about their haemophilia when they were having children, on reflection, they felt it wouldn’t have changed their decision: “It wouldn’t have made any difference anyway. I mean, it wouldn’t stop me.” (Jack). He was delighted that he had boys, as they didn’t have haemophilia: “It stops and doesn’t get passed on to anybody else.”

Two participants felt that, as it could not be guaranteed that their children would not inherit the disorder, they couldn’t justify or bear the thought of passing it on to future generations. They either reduced the size of the family they wanted or adopted children: “As much as I would have loved to have a daughter… I just would be really unhappy if I gave something to my grandchildren and that they are going to suffer the way I’m suffering, because I’m suffering mentally… and I’m suffering because of the bleeding itself. I would have been worried sick if I had a girl.” (Luke).

“But they are not our own, we adopted them, because of haemophilia. Both sides of the family had it. And they didn’t know what was going to happen. So we thought rather than chance it... We’ve never regretted it.” (Lee)

Discussion

The ability to manage pain at home following a bleed or injury is important for people with haemophilia. Two participants revealed that, prior to accessing healthcare services, they had taken aspirin or ibuprofen for pain relief. These drugs are contraindicated for people with haemophilia [16], as they can interfere with the platelet function which is required for effective clot formation. It is therefore recommended that paracetamol and codeine-based medications are used.

Seven of the participants were aware of the standard acronym RICE and were generally diligent in applying the principles of RICE for injuries prior to accessing healthcare. These findings differ from those reported in Nilson’s study, where participants reported that, following an injury, they generally only applied ice without compression or rest [7]. An American national pain study reported similar results to the current study, concluding that in people with mild haemophilia, the most commonly utilised strategy employed to treat both pain and bleeds was RICE [17]. Participants in this study explained that, with maturity, their attitudes and behaviour had changed, and that they had now adopted a more careful and vigilant approach. These results indicate that promoting the RICE principle at every available opportunity is a strategy that is being embraced and is working well.

Bruises are bleeds that occur close to the surface of the skin. While superficial bleeds generally do not require treatment, more significant bruises caused by injury need to be assessed and may require treatment. In this study, bruises, no matter how large, did not always trigger participant’s access to health care.

A study by Walsh reported no significant difference in pain between affected males with haemophilia and a control group [10]. However, the generic Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) quality of life scale tool used may not be adequate in capturing this information [18]. Nevertheless, participants in both this and Nilson’s study reported that the severity of pain experienced was the overriding reason for accessing health care [7].

Participants acknowledged that reliance on pain as a barometer was not always a fool proof method to accurately assess whether there was a significant bleed, and that sometimes they got it wrong. The fact that some men with haemophilia live with chronic pain may be an influence in this respect, as they may have adopted behavioural and physiological coping mechanisms [19, 20].

In both the current study and that of Nilson, it is evident that, following a bleed or injury, most participants purposely delayed accessing health care [7]. The reason for the “wait and see” strategy was the preference of individuals to wait until the haemophilia centre was open rather than attend an A&E department.

In the UK, there is acceptance that attending A&E departments may involve delays, and. feedback from patients’ experiences of waiting times has prompted them to come under scrutiny [21]. As a result, work is being undertaken to improve waiting times in hospitals across the UK. The national standard indicates that no patient should wait more than a maximum of four hours between presentation to A&E and discharge [22].

Participants in this study have developed an aversion to waiting in A&E departments, although their expectations of long waits did not always match their experience when they actually accessed A&E. This may indicate that the efforts to reduce A&E waiting times are leading to improvements.

Participants identified an overall lack of knowledge about haemophilia and its management among A&E staff. This perception may be a reflection of haemophilia being a rare bleeding disorder. Unlike breathing problems, which is one of the most commonly reported reasons to attend an A&E department [23], haemophilia is not something that is often encountered. The lack of exposure of A&E teams to haemophilia may be compounded by participants consciously avoiding attending A&E departments. Participants generally waited to attend their haemophilia centre for treatment, even if this meant a two-day delay.

In this study, participants greatly valued advice from their haemophilia team and accepted guidance about the management of their bleeds and injuries. This attitude was unlike those reported in Nilson’s study, where there was a general mistrust of information received from haemophilia teams, in part due to how staff interacted with them and how information was presented [7]. In the present study, participants reported having a great deal of respect and an excellent rapport with their haemophilia team, whom they trusted to deliver the best care. All participants reported that they attended their yearly medical reviews and that it was a useful opportunity to update and clarify any issues, and to get advice. This attitude differs from those reported in Nilson’s study, where participants only attended reviews if they had experienced a recent bleed [7]. Participants in the present study were extremely open to any advice given by their haemophilia team due to the trust they have in them, and the care and management that they provide. The one area that was consistently ignored by participants was advice regarding the need to attend A&E departments in a timely fashion following an injury or bleed. Attending A&E only when pain was unbearable was an attitude that was firmly entrenched.

Returning descriptive findings to study participants in order to validate them, is a requirement of Colaizzi’s methods. Controversially, it could be argued that individuals may adapt and change their minds when they see the data, and that this may interfere with the true meaning gathered initially [24]. However, no participant in this study requested changes to their transcript

One lesson learned during the course of this research was not to assume that there would be a lack of participants willing to engage. Nilson’s study emphasised how challenging recruiting young men with mild haemophilia had been in Canada [18]. In that study, 151 potential participants were contacted, but only 13 participants responded. In contrast, recruiting mild haemophilia patients in the UK for the purposes of this study did not raise the same low response rates 12 potential participants were selected and all 12 responded, with eight opting to enrol. This may be due in part to different attitudes towards involvement in research in different countries. It may also be partly due to the paucity of research focused on mild haemophilia. Research fatigue was not evident within this group, and many were keen to participate in future studies.

People with mild haemophilia may not have experienced many injuries or bleeds, so nurses need to be more vigilant when explaining what constitutes a significant bruise, bleed or injury, and the need to access health care in a timely way.

Participants placed a high importance on attending annual medical reviews. At these reviews, nurses need to be proactive in ensuring up-to-date information on current medications and which medications are contraindicated. Working in partnership with pain specialist teams would help to ensure that individuals with more complex and chronic problems are provided with tailored plans.

Promoting the RICE principle is a strategy that is being embraced and is working well. The RICE principle has been expanded to the acronyms PRICE (protection, rest, ice, compression and elevation) [25] and POLICE (protection, optimal loading, ice, compression and elevation) [26]. Updating individuals on these changes and the rationale behind them would help to ensure that, following an injury, the actions required to treat are implemented in a timely manner.

Historically, health care professionals have tried to restrict participants’ choices of sport activities. The findings of this study clearly indicate that participants have always been actively involved in a wide range of sporting activities. Attempts to place restrictions on what activities they can participate in are not being heeded. More teamwork, incorporating the expertise of physiotherapists, is required in order for individuals to adapt activities to accommodate their own physical abilities.

Haemophilia teams need to reassure patients about attending A&E. In order to address the issue of A&E staff’s perceived lack of knowledge about haemophilia care, more extensive work needs to be done to ensure that up-to-date guidelines and information about the care and management of haemophilia is readily accessible and available to A&E staff. Clarity of information as to whom and how to contact haemophilia teams in order to seek advice at any time also needs to be made clearer for all A&E staff. The majority of participants in this study reported that they currently have an up-to-date bleeding disorder card and that they generally carry it with them. Those that do not should be encouraged to carry and present their card when attending A&E departments.

Most haemophilia centres are only open during normal office hours, Monday to Friday, between 9am and 5pm. Alternative working hours patterns may need to be considered: listening to patients and finding ways to accommodate their preferred choices is central to the pledges made to help reform the NHS [21, 27]. Having a haemophilia centre open outside of normal working hours would also help alleviate the apprehensions of some participants. More work needs to be done to ensure that A&E staff are fully aware of which hospital sites hold a stock of clotting replacement products and how to get hold of them in a timely fashion.

Limitations of the study

In this study, seven participants had haemophilia A and one had haemophilia B. Haemophilia A affects approximately 80% of the haemophilia population, whilst 20% have haemophilia B. As patients with mild haemophilia A and B would experience the same issues in accessing health care, it was decided that an uneven distribution of A and B would not influence the results or cause any major bias.

The number of participants involved in the study was a limitation, as a true saturation of data findings may not have occurred. The use of a larger sample size would further strengthen the study findings.

Conclusion

The study found that the RICE principle for managing bleeds and injuries at home is used by people with mild haemophilia. Pain severity is used as a guide for when to access an A&E department. Following a bleed or injury, there is a preference for waiting until the haemophilia centre is open, rather than attending an A&E department, even if this entails a delay in obtaining adequate care. Reluctance to attend an A&E department is mainly due to perceived long waiting times and a lack of knowledgeable staff. More work needs to be done to encourage participants to access health care provision in a timely fashion following a bleed or injury. Haemophilia teams also need to work in collaboration with A&E staff to ensure that up-to-date guidelines and information about the care and management of haemophilia are readily available.

Less restriction is placed upon individuals with mild haemophilia nowadays. Most people in this study reported living well with mild haemophilia; however, some perceived it had a limiting effect and was not “mild” in its impact on their lives. In order to broaden understanding of the experience of living with mild haemophilia, a study of participants’ access to surgical procedures and operations is also required.