In 1996, in response to increasing patient waiting times and a growing shortage of physicians, Dr Ms Els Borst-Eilers, the Dutch Minister of Health, proposed that specially trained nurses should take over a range of specific tasks from physicians. The following year, the first Master of Advanced Nursing Practice was launched at the Hanzehogeschool in Groningen, with the first nurse practitioners graduating in 2000 [1]. By 2009, research confirmed an increasing need for Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs) in the somatic field [2]. Over time, the training and work accountability of the APRN has been extended, with a focus on improving professionalism in the field.

After obtaining the appropriate master’s degree, nurses may be registered as an APRN in one of five nursing specialties:

acute care in somatic disorders

intensive care in somatic disorders

chronic care in somatic disorders

preventive care in somatic disorders

mental health.

Nurse practitioners must be registered with the Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland Verpleegkundig Specialisten (V&VN VS), the Dutch professional organisation representing nurse practitioners, before they can be registered in the Ministry of Health’s Beroepen in de Individuele Gezondheidszorg (BIG) Register, which confirms and clarifies the authority of individual health professionals. In both cases, registration is valid for five years.

The V&VN VS provides nurses with a personal digital portfolio. In order to qualify to register for the next period of five years, the APRN must provide evidence of sufficient work experience and professional development. In addition to information on date of registration and nursing specialty, the digital portfolio comprises four folders:

Work experience

Education (minimum of 100 credit points)

Other skill- and experience- enhancing activities (maximum of 60 credit points)

Peer reviewing (minimum of 40 credit points)

At the end of the registration period, a form is completed, signed by the appropriate staff and uploaded to the digital portfolio. During the registration period, the APRN must fulfil a minimum of 4,160 hours’ work experience, of which at least 2,080 hours must involve direct patient care. This may include any patient-related activity, but not work based in research, education or management. They are also expected to participate regularly in professional development.

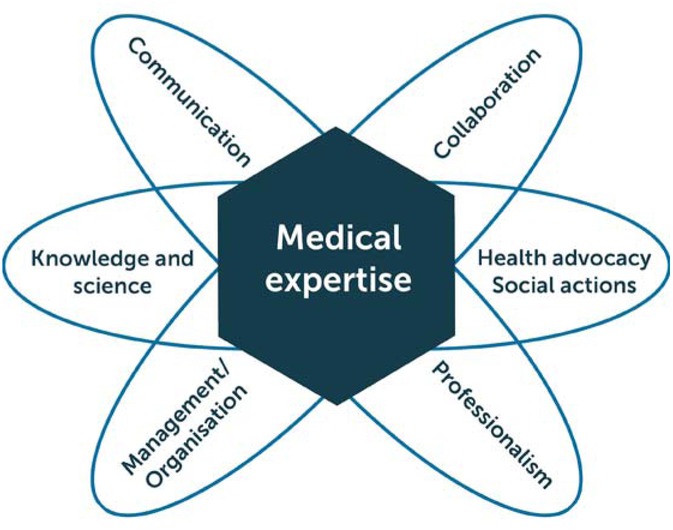

The V&VN offers credit points in the same way as the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. During each registration period, the APRN must obtain a minimum of 200 credit points, spread relatively evenly over the five years and across the seven elements of the CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework: medical expertise, communication, collaboration, management/organisation, health advocacy/social actions, knowledge and science, and professionalism [4]. Points may be achieved in three ways:

A minimum of 100 points must be gained through education and training. Attending educational meetings and congresses can provide points, the congress of the World Federation of Haemophilia equals 21 points.

A maximum of 60 points can be earned through other skill-enhancing activities such as being part of a committee, writing an article, doing research or presenting at a symposium. The V&VN decides the number of credit points and the way they are divided among the CanMEDS roles based on the nature of the activity.

The APRN must participate for at least 40 hours (or 8 hours per year) in a peer review group. A minimum of 40 credit points (one for each hour required over the five-year registration period) must be obtained. Peer review was introduced to the V&VN VS portfolio in 2010.

For APRNs, peer review can be best described as a systematic process whereby one assesses, monitors and makes judgments on the quality of care provided to patients by others, measured against the established standard of practice. As such, peer reviewing offers an opportunity to reflect on one’s own professional practice and responsibilities. The purpose of peer reviewing on the context of the V&VN VS is to provide a boost in quality as regards the development of the APRN profession, and to help healthcare professionals improve quality of care.

Peer review groups tend to be formed within the hospital and generally include APRNs from different backgrounds and fields. For APRNs specialised in haemophilia, this makes it difficult to gain good feedback on the management of haemophilia-specific patient problems.

The Netherlands has 16.8 million inhabitants, of whom approximately 170,000 have a bleeding disorder. These patients are registered in one of seven different haemophilia treatment centres. Nationally, there are 29 nurses working in haemophilia care; within this small group are six APRNs, all of whom joined the peer review groups formed within their own hospitals. However, collectively, five of them saw value in forming a peer review group specific to the field of haemophilia. This paper discusses the formation of a haemophilia peer review group (HPR) and summarises the experience of the group’s early meetings.

Methods

Guidelines for peer reviewing were published by the V&VN VS in 2010 [3]. Peer review groups must have between three and five members, each of whom must present a work-related case or dilemma each year to the other members, who are expected to question the case presenter critically in order to give solid feedback. The goal is for the whole group to learn from the case presented. After the session, each member of the group writes a report, which is filed in their digital portfolio. Peer review groups are free to choose the methods used in their sessions, provided the criteria referred to above are reflected in the report.

Our research concluded that the following methods are appropriate to and useful in HPR sessions:

The testing method: Participants identify experiences, knowledge and insights concerning procedures, techniques and methods they should use or wish to use. The subsequent discussion aims to facilitate improvements in the area identified [5]. This method is particularly suitable for peer review in haemophilia.

The feedback method: This is a quick and comprehensive method of peer review, partly different and partly common in width and with a beginning of a critical reflective spread also applicable for the compare time keys and for comparing different approaches to the same problem. The feedback method is particularly suited to groups of up to 30 professionals [5].

The Balint group: Named after Hungarian psychoanalyst Michael Balint, this is believed to be one of the earliest methods of clinical supervision for family doctors/GPs, with a focus on the psychological elements involved in general practice. In terms of its application to peer review, a case presentation is followed by general discussion, with emphasis on the emotional content of the relationship between healthcare professionals and patients. [6]. Typically, there is a presentation describing a specific situation or problem the presenter has experienced in their practice. The subsequent discussion involves a “diagnosis” of the situation, re-examination of the issues involved and advice [5].

The Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS): A competency-based approach to medical education, the CanMEDS framework was established in 2005 to evaluate the continuing development of medical professionals [4]. Compiled with input from several health professions, although CanMEDS has primarily been used by clinicians as a means of guiding self-assessment or auditing practice, pinpointing areas for further development, and evaluating how these efforts impact and improve on patient care, it may also be of interest to a variety of healthcare professionals (Figure 1).

Regardless of the methodology used at each peer review meeting, the presenting APRN submits his/her case to the other group members at least one week before each session, whether as a written document or a slideshow. Each case submitted must include the following:

introduction of patient history, medical history, (physical) examination;

analysis of the case with at least three examples of corresponding literature or guidelines to clarify or substantiate the diagnosis or problem;

dilemmas that may have occurred or did occur in the case presented, and learning points;

the learning objectives set out by the presenter.

The peer review group read the case in advance and consider examples from their own experience which enable them to relate to the particular problem or dilemma, search for related articles/guidelines/protocols, review untouched areas of the case, prepare critical questions, reflect on their own way of handling such a case and formulate learning objectives.

Experience

The first session of the Dutch haemophilia peer review group in 2013 involved discussion of the V&VN VS guidelines, which of the five methods described above would best meet our needs, and confidentiality. It was agreed that the nurse presenting each case would select the method. The number of healthcare workers within haemophilia care in the Netherlands is small, and most know each other well. It was agreed that whatever was discussed in the group would stay within the group, and that all cases or dilemmas should be presented honestly and openly, without concerns about the potential for the spreading of negative comments or criticisms of co-workers.

During the second and third meetings, cases were presented by the APRNs. Although haemophilia is rare, most of our adult patients with severe haemophilia are very well informed about their illness. The testing method was used to discuss a rare case of acquired haemophilia A in a 48-year-old mentally handicapped woman. The points discussed included how to inform the patient; what words should be used, how much information should be given and how to verify whether or not the given information had been understood, both in the clinic setting and during the following days.

The second case concerned an 18-year-old man with severe haemophilia B. He had contacted the clinic complaining about pain in the left groin area. He had treated himself with clotting factor, but the pain persisted for four days, during which time he could not walk or straighten his leg. Neither the APRN nor the physician on call had much experience with bleeds in this area. Again, the testing method was used to discuss the case. Issues raised included whether or not we would recognise a psoas bleed, where to find documentation and the benefits of having a physiotherapist available.

For the fourth meeting, it was decided that all of the APRNs would present a dilemma concerning haemophilia care. As not all members of the group were able to attend, four dilemmas were presented, ranging from cost perspectives to differences in the treatment of haemophilia between the 1950s and now.

Discussion

As healthcare professionals it takes courage for us to be entirely open about the way in which both our centres and we, ourselves, work, to openly present and discuss our own strengths and weaknesses, and to explore the limits of our knowledge. The atmosphere of the meetings we have held has been friendly, collaborative and non-judgemental. It is important that all participants are able to speak freely about what they have done, how they feel, and what they would like or have been unable to do.

Peer reviewing is, by its nature, an evaluative process and is intended to raise personal awareness of practice, i.e. “What am I doing and do I still work according to existing best practice guidelines?” In order to attain positive results, it is important to implement peer review in an organised and structured way. The literature discusses a wide variety of quality-enhancing methods covering peer review learning groups. Based on our first haemophilia peer review sessions, which involved a frank exchange of views and a sense of freedom of expression, we felt that the methods and frameworks were achievable .

The seven CanMEDS areas (Figure 1) are used by the V&VN VS to evaluate the competencies of the APRN. Following the peer review group meetings, each participant identified, according to a percentage, a maximum of three CanMEDS areas according to their own learning focal point during that session. The outcome in percentage of CanMEDS areas varies per participant. For example, with regard to the case concerning acquired haemophilia, the main focus for some was a need to update their knowledge in this area, while for others the emphasis was on communication skills.

Conclusion

Starting a peer review group presented a number of challenges, including the creation of a safe environment for all participants, establishing a good working method, and the need for courage in sharing insights on the way participants work with colleagues within the same work field/place of work. The ground rules must be very clear and respected by all participants.

Working together as a group offers rewards, not the least of which is good learning experience. Through working together, we had the opportunity to learn not only from our own cases, but also from the experiences of other participants and, thus, from other specialties. According to de Haan (2009), the peer review group is a suitable moment of reflection for professionals who work independently and still have much in common in the theme or approach to their profession [5]. The knowledge and insights gained could be put into practice after the meeting.

Learning from, and with, colleagues is essential to gain insight into one’s own working methods. A peer review group contributes to the professionalization of APRNs working in the care of haemophilia and other bleeding disorders through the sharing of knowledge and participation in joint reflection. We found the CanMEDS framework (2005) a useful tool in contributing structure to this process.

According to Berwick (1989) peer review intends to be and should be an “achievement of continuous improvement” [7]. In our opinion, it is essential in improving and enhancing the comptencies of all APRNs in the Netherlands.