Fifty years is a long time in medicine. Improvements in basic science have deepened our understanding of disease, new technologies have improved diagnostic accuracy and new drugs have improved treatment in many diseases and disorders. Haemophilia is a fantastic example of how new developments in basic science can be translated into medical practice.

Life for patients with haemophilia has changed substantially over the past 50 years, from having little or no treatment and short life expectancy to the situation today where patients can enjoy a near normal quality of life and undertake difficult and exciting levels of activity. Much of this can be traced back to the pioneering work of Dr Katharine Dormandy.

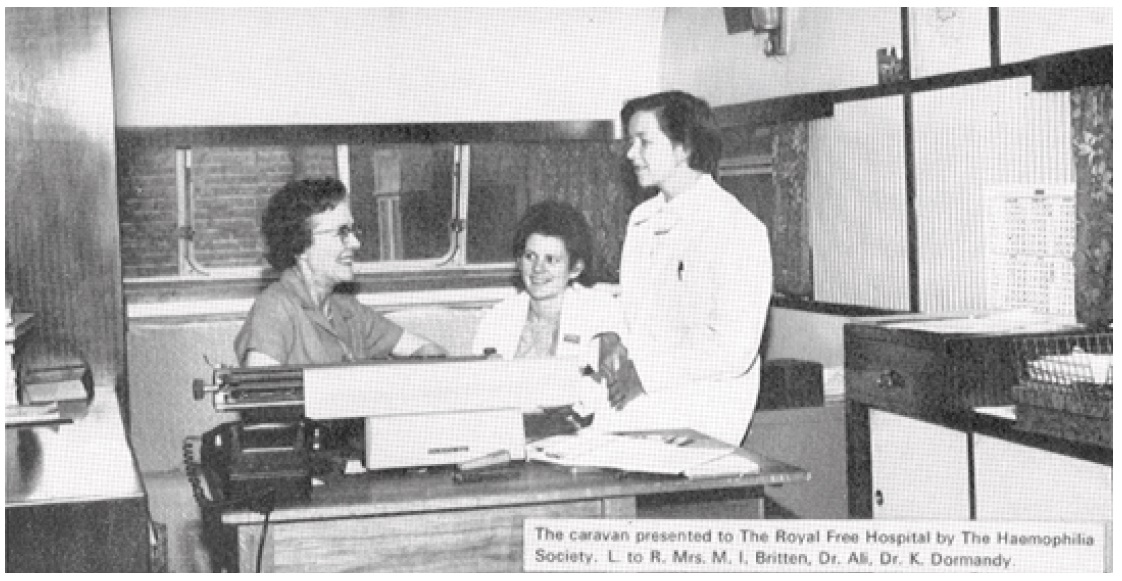

Dr Dormandy had been working at the Hospital for Sick Children at Great Ormond Street since 1959, developing an interest in blood coagulation and the treatment of haemophilia. In 1964 she was appointed senior lecturer and honorary consultant in haematology at the Royal Free Hospital, where she set about organising a haemophilia centre, even though initially she had just five patients. As numbers rapidly grew, the space used for outpatient infusions at the end of a ward at the old fever hospital in Lawn Road, soon became inadequate. In 1965, the Haemophilia Society donated a large caravan but by 1970, the centre had 180 patients and had outgrown the caravan. This time the Haemophilia Society funded a prefab extension on ward 7 at Lawn Road. At this time most treatment was in the form of infusions of fresh frozen plasma. In 1970 the centre took part in the trial production and clinical evaluation of cryoprecipitate and its production was soon taken over by the North London Blood Transfusion Centre. In 1971, the first patients had home treatment with cryoprecipitate, and no longer had to attend the centre for every bleeding episode. In a paper published in 1974, Dr Dormandy concluded “Our experience has confirmed that life for patients with haemophilia is much improved if they are treated at home” [1].

An earlier publication in the British Medical Journal reflects Dr Dormandy’s perspective beyond revolutionising clotting factor delivery [2]. On education, she wrote “It is not enough for young haemophiliacs merely to survive, nor even for them to grow to manhood with good physique – they must also be able to take their place in society as well-integrated, independent individuals, able to earn a salary and support their families…”

In 1977 the Haemophilia Society presented the first RG Macfarlane Award to Katharine Dormandy for her outstanding contribution towards the social and physical wellbeing of people with haemophilia and related disorders.

Determined to establish a first-class haemophilia centre, she set up an appeal fund to finance a purpose-designed building. The centre was finally completed before her untimely death in 1978 at the age of 52. Katharine Dormandy pioneered a holistic approach to haemophilia care. She was very clear what she wanted for her patients. She wanted them to be independent and self-supporting, to become integrated into society, and she wanted them to have home treatment. For all the patients, she provided outpatient and inpatient care, she did home visits, she did home assessments, she did school visits, she managed the finances for the centre and undertook fundraising. She was, in short, a one-man army. And yet, as the number of patients increased, she realised that she needed a team. Among the first members of that team were the specialist nurses. Her first recruit Cheryl Aston was tasked with home and outpatient treatment, as well as intravenous infusion of concentrates and blood products, which was not common practice in other specialities. Subsequent senior nurses included Jane Brunner, Patricia Lilley, and Chris Harrington. In 1966, Riva Miller was appointed as social worker to scope out the potential for home treatment, and in the 1970s, Mr Colin Madgwick, orthopaedic consultant, along with a physiotherapist were added to the team. Dr Dormandy developed a specialist coagulation laboratory and appointed her former research fellow Dr Ron Hutton as principal biochemist and clinical scientist with responsibility for the diagnosis of inherited bleeding disorders and for treatment monitoring.

The development of comprehensive care continued under Katharine Dormandy’s successors at the centre (see panel). In the early 1980s, a combined haemophilia and hepatitis service was developed by Dr Kernoff and Professor Howard Thomas. Then in the mid-1980s, a paediatric clinic was established with Dr Eleanor Goldman. In the 1990s, Professor Christine Lee established combined clinics with Professor Margaret Johnson for HIV and Ms Rezan Abdul Kadir for women with bleeding disorders.

Today, the Katharine Dormandy Haemophilia Centre and Thrombosis Unit is one of the largest haemophilia centres in Europe, with some 1800 patients. It has an enviable reputation for:

The development of a multidisciplinary family-centred approach to haemophilia care

The development of state of the art assays for diagnosis of bleeding disorders

The sharing of knowledge and expertise through an outreach programme

The development of safe surgical protocols for patients with haemophilia

The development of bleeding disorder registries

Defining the natural history and optimal treatment of HIV and hepatitis C in patients with haemophilia

Management of women with bleeding disorders.

Professor Edward Tuddenham was the driving force in purifying factor VIII enabling subsequent cloning and the development of recombinant factor VIII, that led to the development of safe treatment for haemophilia A patients.

Throughout its history, everyone at the centre has recognised the central importance of the relationship with the patients. As a result patients and their families have proven to be a formidable element in the successful development of haemophilia care. Not only have the centre’s patients been at the forefront of championing new and safer treatments and were always willing to take part in trials, they were also willing to share their experience with others.

On 17 April 2015 – World Hemophilia Day – alumni from across the world gathered to celebrate the 50 years since Katharine Dormandy began to establish a haemophilia treatment centre at the Royal Free Hospital. The programme for the meeting shows the impressive breadth of specialties now represented at the centre, and the extraordinary number of renowned people who have worked at the centre, moved away and developed careers elsewhere, and in some cases stayed. Several of those associated with the centre over the years joined the celebration to tell their stories. Further presentations outlined the comprehensive care model developed at the centre. The meeting concluded with a hint of what lies ahead. The articles in this edition of The Journal of Haemophilia Practice give a flavour of the day.