Ethnographic studies aim to observe people in their natural settings in order to gain insight into how they manage their daily lives, what they value in their lives, and what factors adversely affect their ability to live as they wish

©Shutterstock Inc

Haemophilia is an X-linked chromosomal coagulation disorder, characterised by a deficiency of coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) in haemophilia A or of factor IX (FIX) in haemophilia B. The global incidence of haemophilia is approximately 1 in 10,000 births, with haemophilia A accounting for 80-85% of the total haemophilia population [1]. Haemophilia varies in severity with most affected individuals experiencing bleeding into joints, muscles or soft tissues. These bleeds can occur spontaneously or as a result of injury, trauma or a surgical procedure. The greater the reduction of factor level in the blood, the greater the likelihood of experiencing repeated bleeding episodes, which can lead to long-term musculoskeletal complications such as degenerative arthropathy, synovitis and joint deformities [2]. Contemporary haemophilia care in the United Kingdom recommends prophylactic treatment for all children and some adults with severe haemophilia, which reduces the frequency of joint bleeding. In children and those with good joint health, it is possible to achieve an annualised bleed rate of zero [3]. This treatment approach has been considered routine practice for children with haemophilia in the UK since the 1990s. However, a degree of haemophilic arthropathy is present in most people with haemophilia over the age of 25 years, and is usually severe in those over 40 years who grew up with little or no access to any kind of treatment. Arthropathy is likely to affect multiple joints, most frequently the knees and ankles, leading to reduced mobility and chronic pain, impacting on quality of life (QoL). This is exacerbated in patients who have, or had, inhibitors where bleeds remain less responsive to treatment.

Elander reports that joint pain affects large numbers of people with haemophilia and that the pain has a significant impact on QoL [4]. He states that haemophilia healthcare providers do not routinely assess pain or encourage self-management approaches to pain control. In a survey of 78 adults (ages 18-70 years) with severe haemophilia, two thirds had more than one painful joint, with the ankle cited as the most common site of pain. This was an important factor in the restricted mobility they experienced [5]. The presence of pain, increasing age, severity of haemophilia, positive inhibitor status and unemployment are all factors that can result in reduced QoL among people with haemophilia [6], this impacts upon psychosocial well-being. In a literature review, Cassis et al report that psychosocial factors including physical ability, pain, well-being, QoL, stress, anxiety, depression, education and family relationships impact on patient/family social and psychosocial experience [7].

Over the past few decades, treatment of haemophilia in the developed world has advanced such that the majority of patients can expect to live long and active lives. Nevertheless, managing haemophilia, particularly for those with inhibitors, presents healthcare professionals with a number of challenges. While there are now effective treatment options for managing bleeding episodes as well as a whole range of additional support services such as physiotherapy and genetic counselling, the patient experience of haemophilia and how it affects daily life is something about which health professionals still know little [7].

Ethnography is a qualitative research methodology that involves observing people in their natural, real-world setting, instead of in the artificial environment of focus groups, in hospital settings or other similar scenarios. The aim of ethnography is to gain insight into how people live, what they do, how they manage their daily activities, what they value in their lives and what adversely affects their ability to live as they wish. HaemophiliaLIVE is a UK ethnographic study coordinated by Bedrock Healthcare Communications Ltd and funded by Novo Nordisk Ltd. It was developed with the aim of discovering the concerns, priorities and support needs of a wide demographic sample of people with haemophilia across the UK. The underlying expectation was that insights gained into the daily lives of people with haemophilia and their families would enable haemophilia centres to promote care and support to meet the needs expressed by patients in this research.

Materials and methods

An advisory board consisting of the authors of this paper worked with Bedrock to develop the study design, ensuring patient confidentiality within the boundaries of UK safeguarding legalities. The study was advertised in four haemophilia centres across the UK with patients contacting Bedrock if they were interested in participation. This methodology has been used in another long-term condition and was deemed to be market research, and as such ethical approval was not required [8].

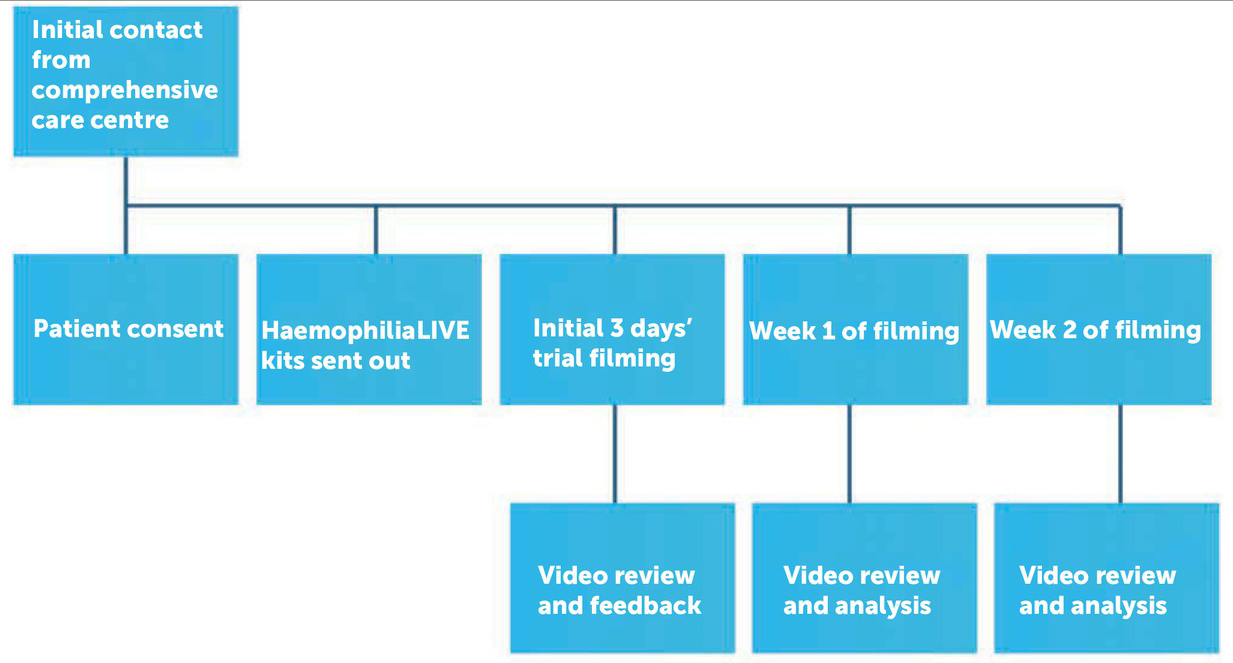

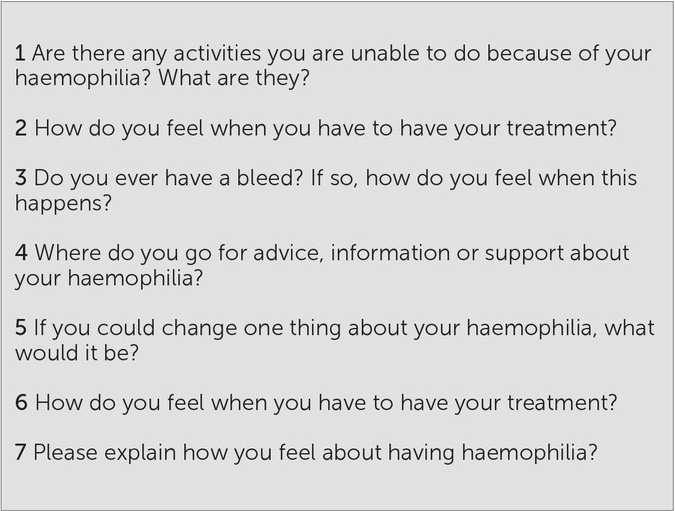

In all, 16 families/individuals from four comprehensive care centres across the UK consented to take part in the study. Each family received a HaemophiliaLIVE kit (Figure 2) comprising video recording equipment, seven sealed envelopes each containing a “secret question” (Figure 3) and pre-paid envelopes for secure return of the SD memory cards. The kit also contained a booklet with clear instructions on the methodology, as well as timelines for when to open the “secret questions” and when/how to return the memory cards. A simplified user guide for the video camera was also created specifically for the project, and contained tips on how to achieve optimum quality footage.

At set times during the study period, participants were asked to open, on-camera, one “secret envelope”. The questions were adapted for adults, children and families and were used to generate immediate responses that could be explored out loud as a monologue to camera.

An initial three-day trial filming was carried out by the participants with recordings being sent back for review. Advice on how to improve the quality of filming was provided if necessary. After this, the participants recorded aspects of their daily lives at home, every day over a period of two weeks. Footage was returned at the end of each week (Figure 1). The recordings all took place between 29 May and 31 August 2013.

Results

Over 2,000 minutes (or 33 hours) of footage was obtained from the 16 participants: four families with children aged under 5; four families with children aged 8-12 years; two teenagers aged 16 and 19; two young adults aged 22 and 24 years; and three men aged 41-62 years. Six of the patients had a current inhibitor. Further patient and therapeutic details can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1

Summary of patient demographics

Without exception, participants reported having enjoyed their involvement in HaemophiliaLIVE and were very positive about the clarity of instructions and ease of use of the kit. They described the value of taking part in such research in terms of having time and space to think about haemophilia and its daily impact on their lives, both positive and negative.

Participants also acknowledged the project’s potential benefits for healthcare professionals who “don’t know what it is like to live with it”, and for other people with haemophilia and their families. Several participating parents said that they wished they had had access to this type of initiative when their child was diagnosed.

Overview of findings

Many participants expressed complex health and/or social issues; family relationships, school, employment and travel were often significantly affected, particularly for those with an inhibitor, some of whom worried about needing large volumes of medication. Although parents expressed anger and sadness about their children’s haemophilia, the children and young people themselves were generally more accepting and felt that the condition was part of who they are. Parents felt that school teachers often did not fully understand the implications of their children’s haemophilia or make sufficient allowances for it. Conversely the adults with haemophilia reported that their employers were understanding and made additional provision for their condition.

Pain was the one subject that was most commonly mentioned in the recordings; this was predominantly by the adult participants and by children with inhibitors. These individuals also expressed fear about loss of mobility and independence as part of the ageing process, and about forthcoming orthopaedic surgery.

Diagnosis

The experience of a haemophilia diagnosis was seen as one that affects the whole family, not just the immediate family of parents and siblings but also grandparents and other members of the extended family. There was great variation between families in the way the haemophilia diagnosis was communicated and received. For some, where there was no previous family history of haemophilia, the news came as a complete shock. The mother of participant 9 (aged 16) recalled her experience of her son who was diagnosed aged 16 months after a mouth bleed:

“They gave me a booklet and told me to get on with it. It wasn’t a problem unless he needed an operation. He had factor for his mouth bleed and blood and then he got an inhibitor – I thought ‘why me? What had I done to deserve this?’ It took me a long time to realise this was only a tiny part of my fantastic boy, and he is a fantastic boy.”

For others, there was already the knowledge of a family history – this enabled some families to be significantly better prepared than others to receive a haemophilia diagnosis, either by knowing the diagnosis antenatally or soon after birth:

“We knew before he was born, I am a haemophilia carrier so I knew there was a 50:50 chance; to add to this we are both carriers of cystic fibrosis. We chose to have CVS so we knew at 14 weeks that he had both conditions. This gave us the time to adapt to the diagnoses before he was born. We still chose to have him knowing all that he was.” (Mother of participant 2, aged 1.5 years)

“We knew on the day he was born. I’m a carrier so knew there was a 50% chance I would pass it on. The only worry was taking blood from a little baby boy who might have haemophilia.” (Mother of participant 1, aged 1.3 years)

As demonstrated above, there was also considerable difference in the quantity and quality of support and information gained and required by parents and families of newly diagnosed children, since each case had its own unique features. There remains a paucity of data on how the families of newly diagnosed children with haemophilia are supported at this crucial time. There are likely to be gender differences between mothers and fathers in terms of both support needs and amount of face-to-face healthcare professional contact. Psychosocial stress could be reduced by introducing coping strategies for parents [9 10] and coming to terms with the normality of life with haemophilia can lead to positive outcomes for children and their families [11].

Family relationships

The impact of haemophilia on family life was reported to be high by the participants of this study, given the necessary restrictions on a range of activities because of perceived bleeding risk, and the need for frequent last-minute cancellations following bleeds being particularly unwelcome. Key themes raised included the impact that haemophilia has on marital relationships. Two participants, one mother and one affected individual, stated that haemophilia was a significant part of their marital disharmony, with both relationships ending in divorce. In both families the effect of haemophilia on their working life exacerbated the difficulties they were in, with the mother of participant 6 stating:

“My career ended with his inhibitor. No way could I hold down a full time job. There was a massive loss of earnings, that didn’t help us at all. Now I have a working at home job, so I can work round bleeds and hospitals and everything else that haemophilia throws at us”.

The impact of haemophilia on siblings, trying to deal with the affected child lovingly without being overprotective of him to the detriment of the other children, were concerns expressed by parents. One mother of 18 month old twins (participant 3), with one affected by haemophilia, described the additional pressure she felt under to look after them both equally:

“There is this extra pressure about him; with factor, extra monitoring etc, it’s worse because they are both exactly the same age. How am I supposed to keep an equal eye on them both? So I keep an eye on both of them, but more on him and I ignore her.”

Emotional stress and financial burden have been demonstrated to be two of the top three burdens for parents of children with haemophilia in the United States (the other being witnessing their child in pain). Caregiver burden is reduced through education and support and learning coping strategies, alongside sharing experiences with other affected families [12].

In some senses, having haemophilia appeared to impact families more than the children themselves. Parents often reported being angry and upset about their children’s condition, while the children were generally able to accept their haemophilia as part of who they are:

“I’m alright about it – to be honest I’ve never known any different, I’m fine having it – it’s part of who I am …. I don’t see there is any limitations, always done what I wanted – football, BMXing, there really are no limitations..…with factor!” (participant 9, aged 16 years).

The phenomenon of self-acceptance of haemophilia, coming to terms with it and seeing is as part of the self is well recognised. The concept of ‘this is it, this is normal for me’ is described by Atkin and Ahmad [13] with resilience being developed during adolescence and early adulthood [14].

Pain

Pain was a common issue raised by the older participants as well as those with inhibitors. There was a clear division between older patients with haemophilia and younger ones (except for those with an inhibitor, for whom life was more difficult generally). Whereas the younger patients usually felt less restricted about their activities and daily lives, adults who had lived with haemophilia for severaldecades tended to express greater fear of pain and disability.

The older participants with haemophilia reported living in constant fear of pain, which often led to them placing restrictions on their activities, to prevent themselves experiencing bleeds and more pain. Some reported that much of their day-to-day behaviour was influenced by the fear of pain and the desire to avoid it. Also present in many patients’ minds was the prospect of needing mobility aids or elective surgery as their condition became progressively worse. Participant 12, a 22 year old who had limited access to treatment as a young child, gave a graphic description of his day:

“I am lying in bed, my right ankle, I just can’t stand on it, I’m on crutches to get about, I’ve been to the hospital this morning, the problem is with the pain – it’s inflammation not bleeding – so yet more tablets, Celebrex 100, paracetamol and 10mg of morphine a cocktail to keep me going until the ankle surgery. I have the insoles and the ankle brace I’ve done everything they [the hospital] say now I need a fusion, usually they do that in sixty year olds – and me, I’m only twenty two. But I had so many bleeds when I was little it’s now just bone on bone and I’m quite worried about where it will all end. And yet I’m still smiling – people admire me for my fighting spirit”.

This ability to cope with long-term joint pain is well recognised in people with haemophilia [15] and is part of an overall coping strategy in which affected individuals are known to use task-oriented approaches to deal with their haemophilia [16]. Pain management, including pharmacological (factor and analgesia), non-pharmacological (physiotherapy, rest, ice, compression, elevation – PRICE), and complementary therapies (acupuncture, music therapy, self-hypnosis and guided imagery), is an important part of haemophilia care [17].

Ageing

There were only three participants over 40 years of age in this study; however four other participants discussed ageing issues. These were two teenagers, both with long standing inhibitors and two participants in their mid-20s, one of whom had limited access to treatment as a child, while the other had played a lot of sport as a child, disregarding treatment recommendations, and now had a stiff ankle. Their concerns included difficulty distinguishing between haemophilic arthropathy and ‘old age onset’ arthritis.

“I am never quite sure if the pain is arthritis of old age or the early onset of a bleed. That element of uncertainty is worrying. Is this just my usual stiff joint or something I should treat?” (participant 15, aged 60 years)

The frustration over impaired mobility led to depression in some patients:

“It makes me feel just a bit down, a bit fed up and depressed about it if you like.’’ (participant 16, aged 62 years).

Fear of what the future might hold was also common among these older participants, who are at the forefront of another new stage of haemophilia care; previous generations of people with haemophilia have not lived long enough to experience the challenges of ageing. For the current older generation of people with haemophilia in UK, there is an expectancy of living well into old age. The need for healthcare for non-haemophilia related issues (such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes [18], cancer and deterioration of mobility related to poor musculo-skeletal health) means confronting new healthcare providers at the same time as coming to terms with retirement, the death of a partner, managing alone with haemophilia, the fear of becoming a burden on relatives and friends and loss of independence. There are little data to report how ageing people with haemophilia cope with these changes [19] or how healthcare providers plan to address them.

Discussion

It is widely recognised that haemophilia has a significant impact on the lives of the person with haemophilia and his family. The challenges of everyday life include managing bleeding episodes, achieving regular school attendance, participating in peer activities, overcoming family and social difficulties, travelling, dealing with schools and employers amongst others. It is not surprising, therefore, that people with haemophilia report a wide range of unmet needs. Ethnographic research, such as that carried out for the HaemophiliaLIVE project, helps to further identify those needs.

If we focus on the four main themes emerging from this research, as discussed above, what can haemophilia health professionals do to enhance the support available for people with haemophilia and their families?

The insights gained into the effects of haemophilia on family life and relationships could act as a basis for the development of innovative strategies to help support patients and their families, particularly at times of stress such as at diagnosis, starting treatment, educational change, undergoing surgery, leaving home etc. As the research showed, there are elements common to most families living with haemophilia, as well as elements specific to each individual family. Thus, for some, one-to-one psychological counselling may be welcome, whereas others would prefer to be pointed towards useful internet sites or support groups where they can meet others in similar situations. Another feature demonstrated in the research was that parents and siblings are often in need of as much support as affected individuals. In fact, it sometimes appeared that the patients accepted their condition more readily than their families. Given the wide variety of needs within families with haemophilia, it seems reasonable to aim to develop a similarly wide range of support and educational tools to help them in different ways – rather than assuming a one-size-fits-all policy.

The impact of receiving a haemophilia diagnosis was not a uniform experience, according to the research participants. For some, the news came as a great shock, mostly in families with first family members affected, while others were more prepared due to existing awareness of the hereditary link within the family. There is certainly a need to ensure that those families for whom the diagnosis is completely unexpected are informed as sensitively as possible. As with the area of families and relationships, handling diagnosis well involves tailoring the discussion and information to the individual needs of each family. Some will wish to know as much as possible, perhaps even during pregnancy with antenatal diagnosis, while others may need time to allow the diagnosis to sink in and will undoubtedly require repeated information provision. Being sensitive to these differing attitudes and providing tailored education and support ensures that haemophilia becomes less daunting for families during this stressful time [10, 11].

While the burden of pain is unfortunately common among those with haemophilia, there is much that we can do to reduce its impact. A multidisciplinary approach to pain management is likely to achieve greater success, with patients being offered access to a range of services that they can make use of as necessary. The psychological aspects of pain should not be neglected, as living with the fear of pain can have a significant impact on patients’ mental and emotional well-being and quality of life [4,5]. We can ensure patients are educated and feel engaged in management options, as well as advising them on strategies for relieving and/or preventing pain through methods other than pain relief medication. This may include supporting concordance with prophylactic factor replacement therapy to reduce further bleeding episodes [4,15], having physiotherapy input (including physical and functional assessment, orthotic provision etc) and encouraging engagement in rehabilitation programmes such as gym based activity and hydrotherapy [20, 21].

The issue of ageing for people with haemophilia is one that has only become prominent in recent years; few patients with severe haemophilia survived to old age before the advent of effective treatments and comprehensive haemophilia care. While this is cause for celebration, it also creates new concerns among patients. For the older participants in this study the fear of what was to come as they aged was clearly present. This represents a challenge for health professionals as well as affected individuals; care protocols will need to evolve and take into account the particular requirements of an ageing haemophilia population. There is growing need to educate and raise awareness of these issues within primary care and in voluntary and community sector organisations to ensure that routine screening and preventive care is delivered to the ageing haemophilia population regardless of their bleeding condition.

In conclusion, ethnographic research with the methodology used in HaemophiliaLIVE provided valuable insights into the daily challenges for people with haemophilia and their families. These insights included coming to terms with the diagnosis, the impact on family relationships, the challenges of work and education, pain management and concerns over mobility and ageing. People with haemophilia and their families, particularly those affected by inhibitors, require additional support from their haemophilia healthcare team, from their schools and other institutions, and from voluntary sector organisations such as charities and patient support groups.