Historically, it has been common for persons with haemophilia (PwH) to adopt a sedentary lifestyle and avoid physical activity (PA) to limit bleeding risk [1,2,3,4]. However, lack of PA contributes to the development of obesity and other comorbidities that can perpetuate worsening joint and muscle health in PwH [4,5,6]. Regular age- and risk-appropriate PA is increasingly recognised for its important role in improving and maintaining musculoskeletal and cardiovascular health, quality of life (QoL), and social and psychological well-being among PwH [2,4,5,7,8,9,10,11], and several haemophilia organisations provide resources to support individualised engagement in PA [5,10,11,12,13,14]. The paradigm shift toward encouraging participation of PwH in regular, individualised PA has largely been driven by the establishment of prophylaxis as the standard of care with either clotting factor concentrates (CFCs; especially extended half-life [EHL] factors) or non-factor replacement therapies [1,5], both of which have substantially reduced joint bleeding rates and deterioration [1,5]. Intravenously administered EHL CFCs and subcutaneously administered non-factor therapies provide PwH with treatment options that can improve efficacy and reduce treatment burden compared with conventional therapies [5,15]. These novel agents offer PwH the potential to lead active lives with greater protection against bleeds and improve QoL of both patients and caregivers [5,15]. However, the evolved haemophilia treatment landscape has also introduced practical challenges such as treatment monitoring. For example, monitoring of factor-based therapies is guided by measurable factor levels, whereas non-factor therapies do not lend themselves to conventional measurements. As such, there is a growing need to consider overall haemostatic potential as a unifying framework to assess treatment adequacy across various therapeutic modalities, including in the setting of PA.

Despite advancements in treatment and increased recognition of the importance of PA, hesitation regarding risks associated with exercise and participation in sports persists in the haemophilia community[1,7]. This may be particularly true for older PwH with severe disease who often live with chronic pain and a greater orthopaedic and musculoskeletal comorbidity burden, which may preclude involvement in vigorous activity[16,17,18,19,20]. For these individuals, views on exercise and involvement in different types of PA may also be influenced by a long-standing fear of falling or injury, potentially leading to reduced risk tolerance[16,17,18,20]. Overall, important questions remain regarding the minimum and ideal haemostatic protection for PwH to safely participate in different types of PA [21,22,23,24,25], and the relationship between PA and bleeding phenotype remains poorly understood [8,21,22].

The aim of this narrative review is to explore the intersection of PA and haemophilia, with a focus on the Canadian perspective in terms of current standards of care and clinical experience, and an emphasis on the critical role of comprehensive care in improving patient-relevant PA outcomes. The term ‘PA’ is used throughout this review to include a broad range of physical fitness and skills-based activities that vary with respect to injury risk level, from activities involving daily mobility (e.g., walking) to engagement in non-sport physical exercise (e.g., jogging, cycling, weightlifting) or planned sports (e.g., basketball). In the first section of this review, considerations for PA in PwH, its role in haemophilia management, and impacts on health and psychosocial well-being are discussed. Current guideline recommendations are then summarised, with a focus on involving the haemophilia treatment centre (HTC) comprehensive care team to support safe participation in PA through shared decision-making and individualised treatment planning. Next, important and evolving roles for behavioural change and wearable technologies in promoting safe participation in PA are addressed. Evidence for minimum and ideal haemostatic protection for participation in PA and the impact of prophylaxis on physical function and activity levels are then reviewed. Finally, limitations concerning prophylaxis, real-world disparities in access to treatment and physiotherapy services for PwH, and other gaps are discussed. The evidence summarised throughout this narrative review should be considered in the context of the inherent limitations specific to the original studies described.

To illustrate practical considerations for prophylaxis to support PA in PwH described herein, a hypothetical patient case example was developed (Table 1). Components of this case example are presented in call-out boxes within each relevant section of the review.

Table 1.

Patient case example illustrating practical applications of guidelines, use of prophylaxis, and the role of the haemophilia treatment centre to promote physical activity in PwH

THE ROLE AND IMPACT OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN PERSONS WITH HAEMOPHILIA

CASE EXAMPLE POINT 1

A 24-year-old male with severe haemophilia A (FVIII <1%) and no history of inhibitors presented to the haemophilia treatment centre (HTC) to discuss optimising his care for increased PA. His history includes a left ankle target joint from recurrent bleeding in childhood and adolescence, but he has remained bleed free for several years on prophylaxis with an EHL FVIII concentrate.

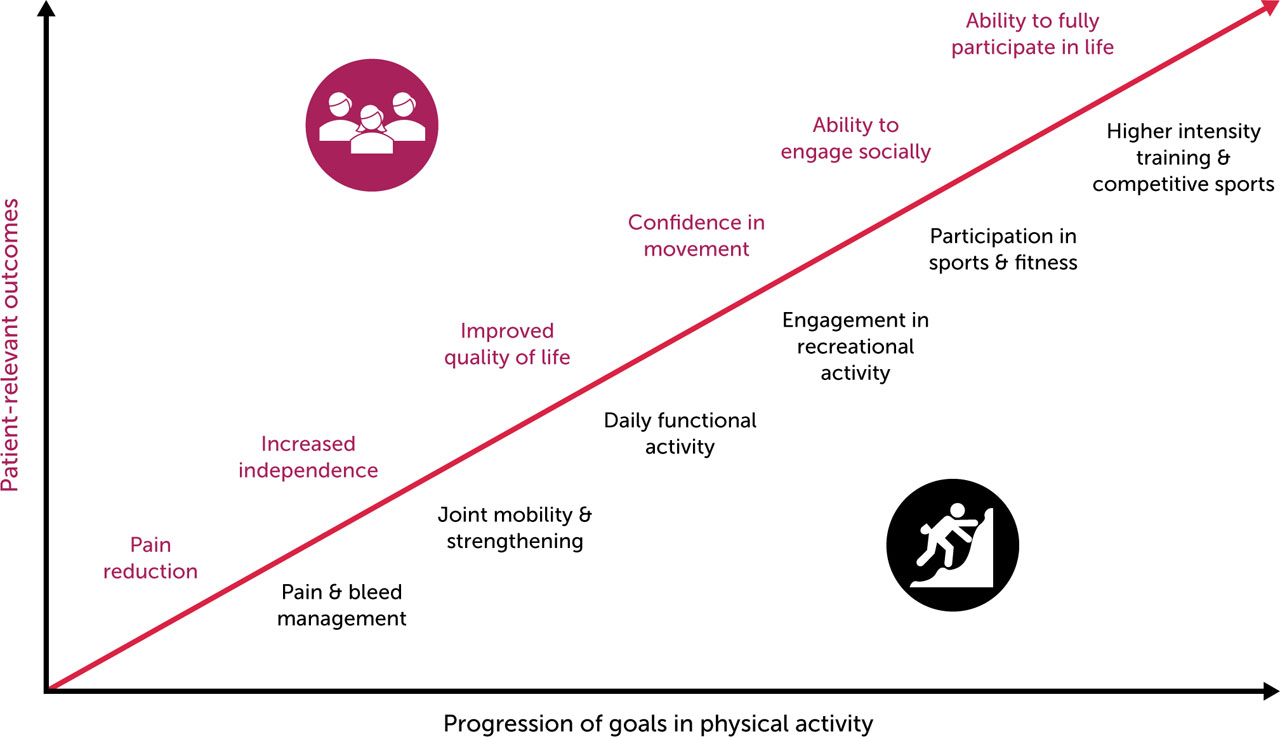

Physical inactivity may predispose PwH to more frequent and severe health conditions including diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, obesity, osteoporosis, and increased joint stress, further exacerbating bleeding and immobility [3,8,18]. With the recent evolution of haemophilia treatment, the role for PA in haemophilia and comorbidity management should be emphasised [4,7,8,18]. The continuum of PA goals and associations with patient-relevant outcomes for PwH is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Associations between progression of goals in physical activity and patient-relevant outcomes for PwH

Note: Progression of goals in physical activity and associations with patient-relevant outcomes are not always sequential or linear. General figure concept inspired by Skinner MW, et al. Haemophilia 2020;26(1):17–24 [107].

Abbreviations: PwH, persons with haemophilia

Clinically, regular PA supports musculoskeletal health by reducing risk of injury, pain, and bleeding while improving joint function, stability, bone density, strength, flexibility, coordination, and treatment efficacy [3,7]. For PwH, types of PA are often categorised by risk level or intensity and energy expenditure (e.g., metabolic equivalent of task [MET] or rate of perceived exertion) [13,22,25]. Although fear of bleeding is often a barrier to PA among PwH [18,26], a systematic review by Kennedy et al (2021) found no conclusive relationship between PA and bleeding among PwH of different severities, nor was there an association between bleeding or injury with high-impact PA in PwH who were treated on demand or with prophylaxis [8]. In addition, the results suggested that PA levels are variable in heterogenous populations of PwH with different disease severity. Findings from a recent prospective, single-centre study in Germany also showed a high level of heterogeneity in PA between PwH, but found no significant differences in objective or subjective PA levels between PwH with mild, moderate, or severe disease [2]. Similar to the findings from the systematic review by Kennedy et al, a study that implemented an individualised, supervised, six-week PA program consisting of twice-weekly exercises in patients with bleeding disorders did not find any adverse effects on exercise-induced injuries, pain, oedema, joint circumference, or bleeding [26]. The exercise program resulted in improved joint motion, strength, and distance covered in the six-minute walk test, with the greatest improvements reported in patients with the most severe joint damage and comorbidities. These collective findings are aligned with recommendations from haemophilia experts (described further under ‘Current recommendations for physical activity in persons with haemophilia’) [7].

In addition to clinical challenges, PwH face psychosocial issues including uncertainty, social restriction, unemployment, emotional disturbances, and reduced self-esteem [27]. The associated distress may negatively impact treatment adherence and overall disease management. In a cross-sectional study of US adults with self-reported haemophilia A or B, more than 50% of participants had moderate-to-severe symptoms of depression or anxiety based on patient-reported outcome (PRO) scores without clinical diagnosis for either disorder [28]. Further, PwH with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms were more likely to have lower treatment adherence than those with mild/no depressive symptoms, and PwH with moderate-to-severe symptoms of anxiety were more likely to have uncontrolled pain and reduced social support than those with mild/no symptoms of anxiety.

It is well established that PA improves mental health, emotional status, and social interactions in PwH and in the general population [27,29]. Sports are typically considered more social than other forms of PA and are particularly beneficial for social connectedness, support, and peer bonding [29]. For PwH, self-efficacy, fun, and social aspects appear to be important facilitators of PA, whereas enthusiasm and interest are motivating factors for sport participation [18]. A patient’s physical, mental, and social status may also be affected by their treatment regimens. For example, a cross-sectional study of Spanish adults with haemophilia found that emotional, mental, and social status were correlated with physical status (including joint health, daily activities, pain, and self-perceived functionality) among those receiving prophylaxis but not on-demand treatment [30]. This is noteworthy given the important role prophylaxis plays in facilitating participation in PA for PwH.

Numerous factors influence the safety and risks associated with PA for PwH [3,7]. Clinically, patients present with distinct bleeding patterns and risks depending on the type and severity of haemophilia, annual bleeding rate (ABR), presence or absence of inhibitors, and maintenance of adequate clotting factor levels (described further under ‘Minimum and ideal factor levels for participation in physical activity’) [3,7,25]. The patient’s overall physical condition (e.g., comorbidities and existing target joints), athletic ability (e.g., coordination, flexibility, strength, and endurance), and muscle health should be considered to determine susceptibility to injury and bleeding risk [3,7]. Additionally, the specific goals, preferences, and support networks of patients must be considered [3,5,7,11,12,13,14]. Overall, the integration of PA into the lives of PwH should be multidisciplinary, carefully monitored, individualised, and based on shared decision-making.

CURRENT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PHYSICAL ACTIVITY IN PERSONS WITH HAEMOPHILIA

CASE EXAMPLE POINT 2

The patient has recently taken up recreational soccer and weightlifting and wants to ensure he is adequately protected while maintaining joint health.

With the evolution of effective treatment options and management strategies for haemophilia, recommendations for PA in PwH have changed. Guidance from the Canadian Hemophilia Society (CHS), National Bleeding Disorders Foundation (NBDF), and World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) can be used to support safe participation in PA, including various types of exercise and sports [5,11,12,13,14]. The principles, approaches, and recommendations from these organisations are described in Table 2. In brief, the CHS has provided several resources to help guide PwH and their families in planning for and engaging in safe PA [10,11,14]. The CHS ‘In the Driver’s Seat’ personalised PA workbook emphasises shared-decision making to consider factors including individual risks, preferences, and health status [14]. The ‘Playing It Safe–Bleeding Disorders, Sports and Exercise’ guidance from the NBDF is a patient- and caregiver-friendly resource that provides recommendations emphasising shared decision-making, age-appropriate and supervised PA, and timing of treatment relative to PA [12,13]. Risk ratings are provided for a variety of sports, exercises, and other types of PA based on risks of injury associated with each activity in the general population to help PwH and their families make informed decisions. The international WFH guidelines for the management of haemophilia include a dedicated section on fitness and PA recommendations for an individualised, monitored, and comprehensive approach to PA in PwH [5].

In addition, a recently published modified Delphi consensus project from the Italian Movement for persons with hEMOphilia (MEMO) study group provided a number of consensus statements on PA and sports in PwH [7]. Among other points, the study group agreed that 1) poor PA is associated with increased risk of obesity and musculoskeletal function changes; 2) coordination, strength, and flexibility help improve joint function and stability, preserve bone density, and reduce overall risk of bleeding; and 3) regular PA enhances stability and joint function and may reduce bleeding risk and associated complications, contributing to improved QoL and interpersonal skills. The MEMO consensus recommendations for adult PwH with no signs of arthropathy include 20–25 minutes of moderate aerobic PA (e.g., walking or biking) per day, 20 minutes of aerobic activity (e.g., jogging or swimming) 4–5 times/week, muscle-strengthening activities 3–4 times/week, structured/organised sports 1–2 times/week, and minimising sedentary behaviour as much as possible. For comparison, the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on PA and sedentary behaviour for adults recommend at least 150–300 minutes of moderate aerobic PA per week, 75–150 minutes of intensive/vigorous aerobic PA per week, or a combination of moderate-vigorous intensity PA along with muscle-strengthening activities at least two days per week, while minimising overall sedentary behaviour [3,31]. The alignment between the recommendations for PwH and those for the general population highlights the considerable progress in scope of safe PA for PwH in the context of proactive disease management. A notable caveat is for older PwH, some of whom may have unique barriers to PA including chronic pain, fear of falls or other injuries (and associated bleeding), and chronic disease [17,18,20]. Additionally, elderly PwH may have reduced energy, balance, mobility, and fitness levels, and limited motivation, confidence, or logistical support. Careful consideration of health status, pain and fatigue levels, and functional capacity is recommended for these patients, along with an individualised plan to gradually increase PA [18].

Table 2.

Resources providing recommendations for physical activity, exercise, and sports among persons with haemophilia

| CANADIAN HEMOPHILIA SOCIETY (2012) [11, 14] | NATIONAL BLEEDING DISORDERS FOUNDATION (2005 & 2017) [12, 13] | WORLD FEDERATION OF HEMOPHILIA (2020) [5] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level | National (Canada) | National (United States) | International |

| Principles | Shared decision-making to consider individual risks preferences, and health status | Emphasises shared decision-making; age-appropriate, risk-appropriate, and supervised PA; and timing of treatment relative to PA | Advocates individualised, monitored, and comprehensive approach to PA to manage unique individual needs |

| Approach and overall contents |

Avoids ‘one size fits all’ approach and acknowledges no activity is risk-free Provides ‘in the driver’s seat’ steps to support patients individualising engagement in PA: |

Overview, risk rating, and safety information pertaining to each exercise/activity/sport Risk ratings: | Recommends: |

| General recommendations for PA | Considerations: |

Considerations:

|

Regular PA and fitness with specific attention to: |

| Activity, exercise, or sport selection | Considerations: | Organised sports tend to be better supervised, but should use judgement and weigh risks versus interests |

Recommendations:

|

| Protective equipment | Emphasises the importance of proper protective gear that supports joints or muscles | Recommends ensuring use of properly fitted safety equipment specific to the sport of interest | Emphasises importance of protecting target joints with braces/splints during PA, especially without factor coverage |

| Consulting with healthcare team and trainers | Recommends that members of the HTC comprehensive care team (haemophilia nurse, physician, physiotherapist, psychologist) be involved in shared decision-making about what is realistic and safe | Recommends meeting with HCP (e.g., physical therapist) for evaluation and training program discussion prior to engagement in PA, focusing on: Providers may adjust infusion schedule/dosing/prophylactic factor replacement according to activity | Consult with a physical therapist or musculoskeletal specialist prior to participating in PA or sport to discuss: Ensure ongoing patient and caregiver education regarding PA implications and responsible participation |

As new therapeutic modalities including factor half-life extension, factor mimetics, rebalancing agents, and gene and cellular therapy emerge, PA recommendations in PwH must also evolve [32]. These innovative approaches may offer improved treatment efficacy, convenient administration routes/schedules, and reduced treatment burden for patients, with a shifting focus on QoL and lifestyle, including PA [32,33]. However, the timing of prophylaxis initiation in PwH will likely remain an important driving factor of PA-related outcomes with new therapeutic modalities, as preexisting joint damage or degenerative joint disease and impaired orthopaedic function may not necessarily improve with tertiary prophylaxis despite reduced incidence of bleeding events [5].

IMPORTANCE OF BEHAVIOURAL CHANGE TO PROMOTE PHYSICALLY ACTIVE LIFESTYLES

Despite available guideline recommendations supporting physically active lifestyles in PwH, the traditional belief that PwH should be discouraged from participating in PA lingers in some settings [3,34,35]. Patient and caregiver education on the importance of maintaining a physically active lifestyle is essential; however, providers should also consider facets of behavioural change to support initiation and long-term maintenance of movement behaviour and adapt these theories to PwH, evolving their techniques over time [3,34,36].

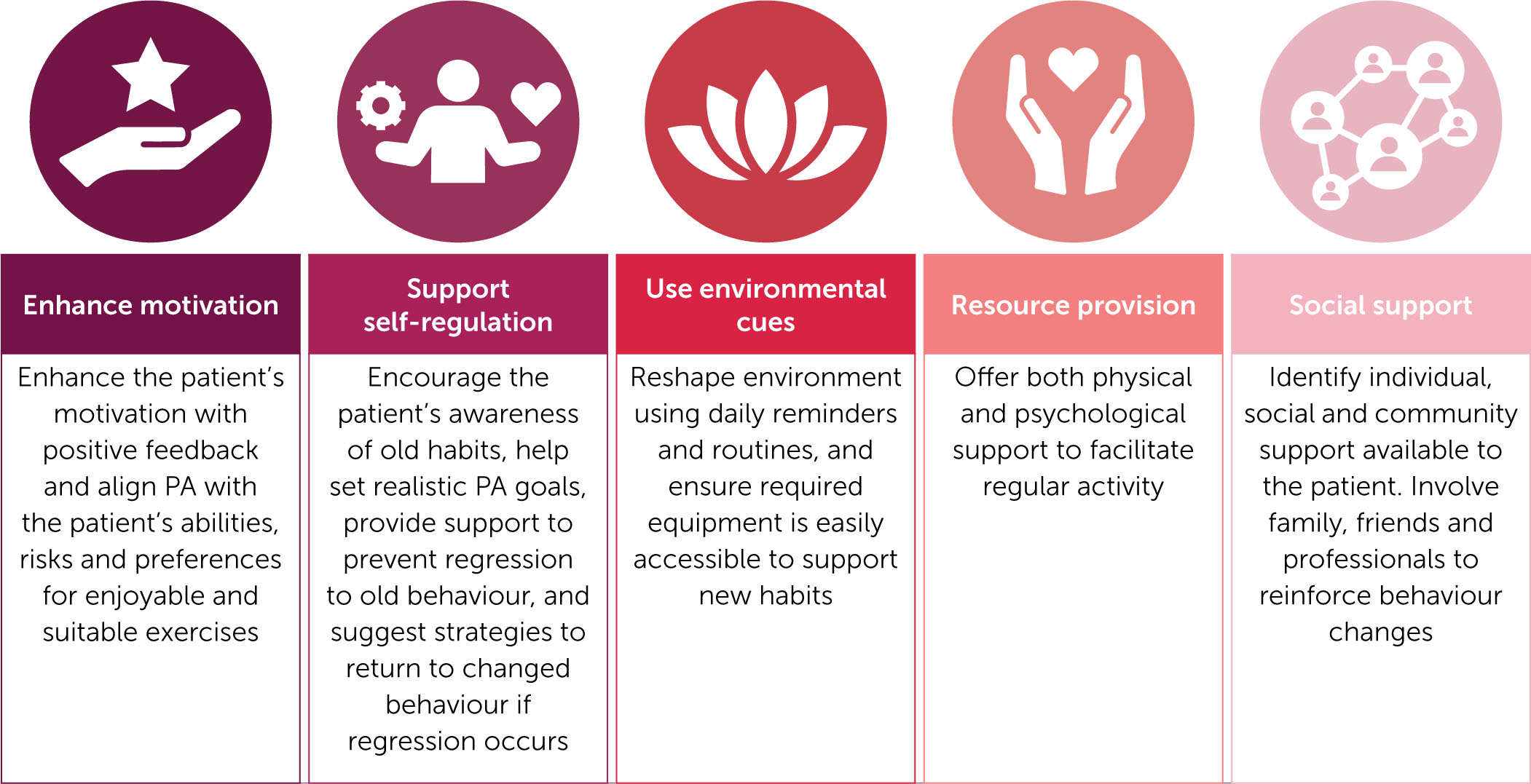

The HTC comprehensive care team plays an essential role in promoting and maintaining a physically active lifestyle for PwH. Blokzijl et al (2021) have adapted previously established factors regarding behavioural change for application by the HTC team in clinical care for PwH [34], as presented in Figure 2. The achievement of PA goals can be assessed during consultations between the HTC comprehensive care team and the patient, and can also be monitored by patients and their caregivers independently using a variety of available methods and tools.

Figure 2.

Behavioural change techniques to encourage maintenance of physical activity in PwH

Content adapted from Blokzijl J, et al. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2021;5(8):e12639 [34].

Abbreviations: PA, physical activity, PwH, persons with haemophilia.

THE ROLE OF WEARABLE TECHNOLOGIES IN HAEMOPHILIA AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Wearable digital technologies have revolutionised PA monitoring by individuals and healthcare professionals (HCPs). These technologies offer a convenient, affordable, and widely accessible means to capture diverse health information in real time. Despite caveats including a lack of validation and regulatory oversight, data reliability issues, security and privacy issues, and data misinterpretation [37], the information obtained from wearable technologies has the potential to inform shared decision-making [38,39,40]. Further, these technologies can help support behavioural modification and increase patient engagement in PA through push notifications, community support, accountability from other users, and gamification [37].

Several studies have shown that wearable technologies have a role in monitoring PA and improving physical health in PwH [1,38,41,42,43]. Prospective observational studies using commercial wearable activity trackers among European patients with moderate-to-severe haemophilia A without inhibitors have shown low rates and intensity of PA, and high rates of sedentary behaviour associated with increased bleeding frequency [1,42]. In a prospective observational study conducted in Spanish adults with severe haemophilia on prophylaxis, approximately 60% of patients met a 10,000-step daily goal at baseline and one-year follow-up, and statistically significant improvements from baseline were observed in daily moderate-intensity activity time and the A36 Hemophilia-QoL Questionnaire physical health domain [43]. Wearable activity trackers have also been paired with haemophilia treatment-monitoring applications to concurrently track injections, factor supply, and bleeds [41]. Overall, findings to date suggest a role for wearable activity trackers in helping patients to self-monitor and improve their PA.

MINIMUM AND IDEAL FACTOR LEVELS FOR PARTICIPATION IN PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

CASE EXAMPLE POINT 3

To personalise the patient’s prophylaxis regimen, he undergoes a pharmacokinetic study of his EHL FVIII concentrate. His results show a peak factor level of 80% post-infusion of 40 IU/kg and a half-life of 16 hours. Based on these findings, he adjusts his infusion schedule, administering factor immediately before soccer matches to maximise protection and tailoring doses to sustain adequate coverage for weightlifting sessions. On average, he requires five infusions per week to maintain his desired level of PA.

Maintaining factor levels above 1% can significantly reduce the risk of spontaneous bleeding and arthropathy [44], with an estimated 18% reduction in risk of bleeding for each 1% increase in factor level [45]. However, target factor levels must be tailored to meet an individual’s unique needs, including PA levels [7,44]. In children and adolescent PwH who engage in moderate-to-high risk PA on a weekly basis, bleeding risk could be reduced by up to 2% for every 1% increase in factor level [46]. There can be considerable inter- and intra-individual heterogeneity in minimum factor levels required during PA depending on the frequency and intensity of participation on any given day [13,44], and a standard prophylaxis regimen may not offer adequate protection for all PwH at all times [23].

There is emerging real-world evidence on factor levels and bleeding risk in PwH during participation in various types and intensity of PA (Table 3). In a study of PwHA (moderate or severe), factor VIII (FVIII) levels at the start of PA were ≤15% in nearly half of PA sessions, and ≤3% in about one in eight sessions; however, factor levels were greater when higher-risk PA were performed, suggesting that PwH adjust their prophylaxis based on the type and intensity of PA [25]. In another study of individuals with mostly haemophilia A (90%; 48% severe), the only significant predictor of a bleeding event during PA was factor level at the time of injury, independent of age, joint health, risk or intensity of PA, haemophilia severity, and ABR [22]. Bukkems et al (2023) also found that factor level was the main risk factor for bleeding during PA in PwHA of any severity, with factor levels of 3.1% and 28.0% reducing ABR by 50% and 90%, respectively [21]. This study found that ABR before study inclusion, preexisting arthropathy, and haemophilia severity were independent predictors of bleeds during PA, whereas frequency and intensity of PA were not associated with bleeding hazard. A pharmacokinetic (PK)-based computer simulation estimated minimum FVIII levels for bleeding prevention across six different types and risk of PA in PwHA (severe) [47]. A minimum FVIII level of 8–12% was associated with a 37% reduction in bleeding risk compared to a target of 1–3%. In a study of paediatric PwHA (moderate or severe), minimum FVIII trough levels to prevent PA-induced bleeds were 3.8% for low-risk PA and 7.7% for medium-risk PA [48]. Multivariate regression showed that both FVIII levels during PA and activity risk level were independently associated with bleeding. In a prospective, 6-month observational study in PwHA (moderate or severe), PA-related bleeding events increased with intensity of PA, but there was no significant association between PA-related bleeds and time since the last FVIII infusion [49]. Although factor levels vary widely across these real-world studies, higher factor levels were consistently associated with stronger protection against PA-related bleeds.

Table 3.

Factor levels and risk of bleeding events during PA in PwH: Evidence from real-world studies

| AUTHOR | STUDY DESCRIPTION | PHYSICAL ACTIVITY | FACTOR LEVELS/TIMING OF INFUSION | INCIDENCE OF PA-INDUCED BLEEDING |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomschi et al. (2024) [25] | Prospective, 12-month, observational study in PwHA (moderate to severe) aged ≥16 years N=23 | 1,011 PA sessions categorised by NBDF risk levels: | Measured at start of PA: | 3 events: |

| Versloot et al. (2023) [21] | Single-centre, prospective, 12-month study in PwH (mild to severe) aged 6–49 years without inhibitors N=125 | 15,999 PA sessions 59% of PwH engaged in high-risk sports (according to NBDF risk levels) and 20% high-intensity (>6 METs) | 6% at time of injury with SIB vs. 12.3% without SIB (p<0.03) | 26 events: |

| Bukkems et al. (2023) [21] | Single-centre, prospective, 12-month observational study in PwHA (mild to severe) aged 7–50 years N=112 | 14,162 PA sessions | 5.9% (range 0–20) during SIB vs. 11.0% (range 0–95) without SIB | 20 events (not described in detail) |

| Konkle et al. (2021) [49] | Participation in PA sessions according to NBDF risk levels: | Time between infusion and start of PA: | 75 events (not described in detail) Mean SIB events per PwH: | |

| Ai et al. (2022) [48] | 373 PA sessions categorised by NBDF risk levels: | 373 PA sessions Median trough levels: | 34 events in 19 patients: |

A real-world study suggests that low-dose, PK-guided EHL-FVIII prophylaxis to individualise factor levels allowed for improved bleeding prevention while meeting PA goals in PwHA (moderate or severe) [50]. After six months, there were significant reductions in ABR and annualised joint bleeding rates, while muscle mass, joint health, and QoL scores improved. Nearly half of patients (n=6/13) had zero joint bleeds despite more than three-quarters (n=10/13) having target joints at baseline. Total FVIII consumption was significantly reduced by 24%, mainly due to a reduction in on-demand treatment for breakthrough bleeds.

Efanesoctocog alfa, a novel EHL FVIII replacement therapy that maintains factor FVIII levels >10% with once-weekly dosing, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing ABR and may improve physical and joint health. In the Phase III XTEND-1 trial, 133 patients with severe haemophilia A aged ≥12 years were assigned to receive once-weekly efanesoctocog alfa prophylaxis for 52 weeks (group A) and 26 patients received on-demand treatment with efanesoctocog alfa for 26 weeks followed by once-weekly prophylaxis for 26 weeks (group B) [51]. In an analysis of group A participants, there were significant improvements from baseline to Week 52 in PROs assessing physical health, mobility, and ability to perform usual activities, and reductions in joint pain. During exit interviews that were completed by a subset of 29 participants (n=17 in group A; n=12 in group B), 75–89% subjectively endorsed improvements across multiple areas of QoL [52]. Although this study did not prospectively assess objective PA outcomes, these observations suggest that efanesoctocog alfa may enhance participants’ confidence in engaging in PA, providing indirect evidence for the physical function benefits of maintaining FVIII levels >10%.

How this evidence translates to clinical practice remains incompletely understood and there is lack of clear consensus on minimal factor levels to target for PwH to safely engage in PA [24]. To address this gap, Martin et al (2020) [23] conducted an expert elicitation study on minimally acceptable and ideal factor levels to avoid bleeds during participation in different types of PA according to NBDF categories of risk [13]. Unsurprisingly, minimum and ideal factor levels increased with higher-risk types of PA [23]. For PwH without preexisting joint morbidity, minimum factor levels ranged from 4% for low-risk activities to 38% for high-risk activities and ideal levels ranged from 9% to 52%, respectively. Target factor levels were slightly higher for PwH with joint morbidity, with minimum levels ranging from 7% for low-risk activities to 47% for high-risk activities and ideal levels ranging from 12% to 64%, respectively. Although this provides some guidance to clinicians, there are inherent difficulties in recommending discrete factor levels for specific types of PA given heterogeneity in individual skill, level and intensity of competition, musculoskeletal health, and bleeding phenotype [53]. There remains a need for more prospective evidence on minimal and ideal factor levels as they relate to an individual’s PK profile, type and intensity of the PA, infusion timing, and other patient-attributable risk factors for bleeding [23,24]. Overall, it seems reasonable to encourage PwH on CFC prophylaxis to time peak factor levels with participation in PA.

A caveat to the evidence regarding peak and trough factor levels for participation in various types of PA is applicability to individuals with non-severe haemophilia. The overall approach could likely be extended to this population, with an emphasis on individualised care and shared decision-making. However, individuals with severe haemophilia are typically on some form of prophylaxis and have learned to self-infuse CFCs, whereas those with non-severe disease may not be on prophylaxis and often manage bleeding with on-demand treatment, which may or may not include CFCs. For these individuals, additional resources and education may be required to help facilitate more physically active lifestyles, including teaching proper infusion of CFCs and/or initiating prophylaxis. Further, depending on an individual’s factor levels, they may not be able to access some therapies based on the approved indication and reimbursement requirements in their country/region (or specific provider policies for private coverage), further complicating guidance for appropriate levels for participation in PA.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND NOVEL HAEMOPHILIA THERAPIES

CASE EXAMPLE POINT 4

Three years after the patient’s EHL FVIII concentrate infusion schedule adjustments, he transitions to emicizumab prophylaxis, reducing his infusion burden while maintaining excellent bleed protection. With this regimen, he continues soccer and weightlifting and, through shared decision-making with his HTC team, incorporates outdoor rock climbing into his routine. His HTC team emphasises ongoing joint health monitoring and provides guidance on participation in higher-risk activities. To ensure his musculoskeletal needs are adequately addressed, he meets regularly with his HTC team, including physiotherapists and haematologists, to assess joint function, optimise his treatment plan, and incorporate strategies for injury prevention and long-term joint health.

Table 4.

Studies evaluating the impact of non-factor and gene therapies on PA-related outcomes in PwH

| AUTHOR | STUDY DESCRIPTION | PA-RELATED OUTCOMES |

|---|---|---|

| Emicizumab | ||

| Shima et al. (2019) [64] | Multicentre, open-label, Phase III HOHOEMI study in Japanese paediatric PwHA (severe) aged <12 years on emicizumab N=13 | |

| Hermans et al. (2022) [59] | Multicentre, single-arm, open-label, Phase III HAVEN 6 trial in PwHA (mild or moderate) aged 2–71 years followed for median of 55.6 weeks N=73 | |

| Astermark et al. (2025) [57] | Interventional, multicentre, single-arm, open-label HemiNorth 2 trial in PwHA (severe) aged 12–60 years followed for a mean of 51.1 weeks N=28 | |

| Warren et al. (2020) [66] | ||

| Nogami et al. (2024) [61] | ||

| Concizumab | ||

| Villarreal et al. (2022) [88] |

|

|

| Jiménez-Yuste et al. 2024 [89] | Exploratory analysis of the multicentre, randomised, open-label, Phase III explorer7 (PwHA/B with inhibitors [any severity] aged ≥12 years) and explorer8 (PwHA/B without inhibitors [severe] aged ≥12 years) trials N=68 (27 from explorer7, 41 from explorer8) |

|

| Fidanacogene elaparvovec | ||

| von Mackenson et al. (2023) [95] | Descriptive long-term follow-up analysis of the open-label, non-randomised, dose-escalation study of fidanacogene elaparvovec in PwHB (moderate-to-severe) N=14 | |

[ii] Abbreviations: CATCH, Comprehensive Assessment Tool for Challenges in Hemophilia; FVIII, Factor VIII; Haem-A-QoL, Haemophilia-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire for Adults; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; METs, metabolic equivalents; NR, not reported; PA, physical activity; PwHA/B, persons with haemophilia A or B.

The introduction of factor-mimetic therapies (e.g., emicizumab), rebalancing therapies (concizumab, marstacimab, and fitusiran), and gene therapies (e.g., valoctocogene roxaparvovec and etranacogene dezaparvovec) over the last decade has dramatically changed the haemophilia treatment landscape in regions where they have been approved [54]. Emicizumab was first approved by regulatory agencies in 2018 and has since been broadly used in routine clinical practice in many regions [55,56], allowing for accrual of data from both clinical trials and real-world practice [57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], including its impact on PA [57,58,59,61,64,66]. Although the efficacy, safety profile, and effects on health-related QoL (HRQoL) in PwH have been reported for novel rebalancing agents and gene therapies in Phase III clinical trials [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85], they have either recently entered routine clinical practice or are not yet being used, limiting the opportunity to assess real-world outcomes associated with these agents. Their impact on PA remains incompletely characterised, with limited or no data on objective PA outcomes available for some of these novel agents.

Emicizumab is a monoclonal bispecific antibody directed against factor IXa and factor X, which mimics the co-factor function of activated FVIII and thereby improves thrombin generation capacity and haemostasis [86]. As a prophylaxis strategy in PwH, it differs from FVIII prophylaxis by its linear PK with peak plasma concentrations achieved in 1–2 weeks and a half-life of approximately 30 days, as opposed to the peaks and troughs with CFCs. Evidence exploring the impact of emicizumab prophylaxis on PA-related bleed rates in PwH is accumulating, with data supporting safe participation in PA among PwH (Table 4). Overall, PwHA (severe) in Phase III studies had clinically meaningful improvements in physical health and overall HRQoL after initiating emicizumab that were maintained over time [65], and participation rates in moderate- to high-risk PA were stable or increased [59,64]. The HemiNorth 2 interventional study (EudraCT 2020-003256-32) also provides evidence supporting the efficacy and safety of emicizumab in physically active PwHA (severe) [57]. Twenty-eight participants aged 12–60 years who completed at least 24 weeks on FVIII prophylaxis in the noninterventional HemiNorth study were switched to emicizumab at the standard label dose for 48 weeks. At Week 49 after switching to emicizumab, HRQoL, PA participation, and joint health outcomes remained stable, while the proportion of patients experiencing zero bleeds increased. Intra-participant comparisons of PA using an activity tracker showed that mean daily step counts, time spent in PA (light, moderate, and vigorous), and sum of METs were maintained between baseline (Weeks 17–24 of the HemiNorth noninterventional study period) and Weeks 41–48 after switching to emicizumab (HemiNorth 2 study period).

These observations are corroborated by real-world evidence showing that 55% of PwH increased their participation in PA and 25% engaged in new types of sports after initiating emicizumab (Table 4)[66]. This suggests that emicizumab could expand health equity in PwH by allowing them to achieve similar PA participation rates as the general population. When PA-related muscle bleeds occur in PwHA on emicizumab prophylaxis, they generally have a slower onset and present more like bleeds in patients with mild haemophilia that resolve within 24 hours with 1–2 doses of CFC [87]. Nonetheless, muscle bleeds can be severe, may have delayed presentation, and may require prolonged management with CFCs; therefore, clinicians and patients should be aware of the need for prompt recognition and treatment.

The real-world, multicentre, observational TSUBASA study prospectively investigated the incidence of PA-related bleeds during treatment with emicizumab [61]. In the final analysis, 129 PwHA (moderate or severe) initiating emicizumab prophylaxis were followed for 97 weeks, and 73 participants logged 968 PA sessions (mostly low-risk activities such as walking or calisthenics) [58]. There were two PA-related bleeding events (0.2% of PA sessions), one associated with basketball and one with fishing. These observations suggest that fixed-dose emicizumab prophylaxis offers adequate protection against bleeding events in PwH during PA, similar to that offered by CFC prophylaxis [21,22,25,58,61].

The impacts of novel rebalancing therapies and gene therapies on PA intensity, type, and frequency among PwH are less clear, as they were introduced more recently than emicizumab and there is no PA-related evidence from real-world studies in routine clinical practice. The Phase III explorer7 and explorer8 trials assessed the efficacy and safety of once-daily concizumab prophylaxis compared with no prophylaxis in PwHA/B with (explorer7) and without (explorer8) inhibitors [74,88], and PA outcomes were assessed in two exploratory analyses (Table 4)[88,89]. Changes in percentage of awake time spent in moderate and moderate-to-vigorous PA from baseline to the end of the main part of the trial favoured concizumab compared with no prophylaxis in PwHA/B with inhibitors, but there were no differences between groups in PwHA/B without inhibitors. By Week 24 of both trials, estimated treatment differences in PROs assessing HRQoL, total health, physical health, and/or sport and leisure favoured concizumab compared with no prophylaxis [69,81].

Phase III trials assessing fitusiran (ATLAS-PPX, ATLAS-INH, ATLAS-A/B, and ATLAS-OLE), marstacimab (BASIS), valoctocogene roxaparvovec (GENEr8-1 and GENEr8-3), and etranacogene dezaparvovec (HOPE-B) in PwH have shown positive effects of these treatments on PROs assessing HRQoL, physical function, and total and physical health [68,70,72,75,76,77,78,79,83,84,85,90,91,92,93]. These findings could indicate an increase in patients’ confidence and ability to participate in different activities; however, no data for objective PA outcomes in these studies were identified. The only haemophilia gene therapy for which PA data were identified is fidanacogene elaparvovec, which obtained regulatory approval in several regions but is no longer being commercialised [94]. In a descriptive analysis of a Phase I/II trial in 14 PwHB treated with fidanacogene elaparvovec and enrolled in a long-term follow-up study, 86–100% of patients reported doing the same or higher-intensity PA at Weeks 52–156 than at baseline (Table 4)[95]. No patients reported a reduction in the amount of time spent engaging in PA or in the intensity of PA at Week 156 relative to baseline. No other analyses specifically assessing PA in PwH treated with novel therapies were identified.

The results of ongoing studies investigating non-factor therapies and PA are eagerly anticipated, examples of which include the Beyond ABR Phase IV study (NCT05181618) and STEP observational study (NCT05022459) of emicizumab. Additional studies assessing objective PA outcomes among PwH receiving recently introduced therapies as well as next-generation factor mimetics (e.g., Mim8 and NXT007) are also awaited.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Regular age- and risk-appropriate PA is an effective and inexpensive way to mitigate chronic health conditions in PwH [3,8,12,18], and it may improve musculoskeletal health and reduce bleeding rates [7,26]. With the advent of new therapeutic modalities including factor half-life extension, factor mimetics, rebalancing agents, and gene and cellular therapies, many PwH are increasingly engaging in PA across a range of intensity and risk levels [8]. Evidence to date suggests that PwH can safety participate in PA of various types and intensity as long as they have sufficiently protective prophylaxis regimens [22,23], although additional factors such as patient age, functional ability, pain and fatigue levels, and extent of existing joint damage/disease should be considered and still warrant further investigation [5,16,17,18,20]. Nonetheless, there is a need to expand beyond bleed rates alone to measure the adequacy of prophylaxis, as haemostatic potential is only one component of facilitating PA in PwH. Shared decision-making between PwH, caregivers, and HTC comprehensive care teams should continue to be emphasised to integrate haemostatic potential within a broader framework that includes individual patient goals, preferences, and bleeding phenotype.

Despite the benefits of prophylaxis discussed herein, predominantly in the context of facilitating engagement in PA, there are limitations and evidence gaps associated with their use. The long-term effects of prophylaxis remain incompletely characterised, making it difficult to predict lifetime risks and outcomes for PwH [96]. This emphasises the need for ongoing assessment and personalised care for PwH on prophylaxis [97]. In addition, prophylaxis accounts for the majority of total health care costs among PwH regardless of the treatment regimen (FVIII replacement concentrates, bypassing agents, or non-factor therapies), and costs increase with the intensity of treatment and haemophilia severity [98].

Prophylaxis has become the standard of care for PwH in Canada and globally [5,54,56], and emicizumab is the most widely adopted non-factor therapy for PwH in developed countries to date [15,54,56]. Nonetheless, there are notable global disparities in access to comprehensive haemophilia care [99,100,101]. For PwH in lowand middle-income countries, access to prophylaxis, pain management strategies, disease education, and support systems (e.g., haematologists, physiotherapists, social workers, and psychologists) is often limited due to a lack of availability and prohibitive costs, leaving on-demand treatment as the only option for many patients [100]. Although initiatives such as the WFH Humanitarian Aid Program have helped to reduce this gap by providing support and donating treatments to thousands of patients in low- and middle-income countries [56,102,103], disparities in access remain. Separately, individuals in high-income countries may not always have consistent access to comprehensive haemophilia care [104,105], and specialised physiotherapy services for persons with bleeding disorders are often limited in availability or highly variable in practice [104,106]. Collectively, adopting a multifaceted approach that supports international collaboration, integration of digital health and telehealth technologies, specialised healthcare services, and advocacy groups could address inequities in care among PwH [100].

There is also a need for more objective and holistic assessments of PA in clinical research and real-world practice settings. Although PROs currently used to assess HRQoL in PwH include physical health or functioning domains, they do not capture true PA levels. More specific assessments of PA to help guide treatment decision-making could include: patient-reported type, intensity, and frequency of PA, as well as barriers to and facilitators of PA; use of wearable activity monitors; comprehensive joint health assessments; psychosocial impact of haemophilia treatment and PA (e.g., self-efficacy, mental health, and social engagement); pain and fatigue tracking; and functional mobility tests. Further, the improvements in haemophilia management that have allowed PwH to participate in PA to the same extent as individuals without haemophilia warrants a shift away from haemophilia-specific measures of physical health towards those used in healthy individuals, albeit with consideration of the compounding impact of increased age on functional capacity and frailty among PwH compared with the general age-matched population. Although various PA-related outcomes are being used in clinical trials, the lack of consistency presents a challenge for indirect comparisons between studies and across novel treatments. Standardisation of PA-related outcome collection across trials and development of a core outcome set for PA are important goals, particularly given the lack of available PA data for many novel therapies. Overall, as the therapeutic landscape and evidence base continue to evolve, so too must PA recommendations in PwH, shifting toward personalised guidance that reflects both individual haemostatic protection and functional goals. HTCs will continue to play a critical role in this evolution, supporting PwH in safely achieving their PA aspirations.