Women with bleeding disorders have historically been underdiagnosed and therefore undertreated, thereby experiencing serious bleeding episodes [1,2,3,4,5]. Women who carry the gene for haemophilia A or B can have coagulation factor levels in the lower range. As well as suffering bleeding symptoms present in men with haemophilia, additional burdens include HMB and/or post-partum bleeding [6,7]. Research indicates that HMB is the most common bleeding symptom in women with a bleeding disorder [1,2,4,8]. Women with undiagnosed bleeding disorders have higher rates of complications in pregnancy and childbirth, including miscarriage, antepartum bleeding, epidural, spinal or perineal haematoma, postpartum haemorrhage and maternal mortality [1]. In developed countries, although awareness regarding the importance of correct diagnosis and adequate treatment of women with bleeding disorders has improved, many women remain undiagnosed or are diagnosed late in life or after one or two pregnancies [1,2,5,6,7,8]. Without access to adequate treatment, hysterectomy can be the only solution to avoid uterine bleeding [1,2]. In developing countries where there is limited access to screening capabilities and treatment, most women with a suspected bleeding disorder remain undiagnosed and without adequate treatment, resulting in a major public health problem [1,3,8].

The assessment and interest of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is gaining way as an important measurement of health care outcome. Studies show that QoL may be impaired for teenagers and women with HMB [2,4,5]. Psychosocial impacts may be exacerbated in some cultures. One Iranian study, for example, shows that being a carrier of a hereditary disorder in Iran has a profound effect on women’s psychosocial life due to the society’s negative perception, with impacts including difficulty in getting married [8].

There is a need for greater awareness of the prevalence of bleeding disorders in women and girls amongst health care professionals [6,7]. Referral to professional care at coagulation units or haemophilia treatment centres is important for correct diagnosis and follow-up [5]. With correct diagnosis and treatment, women with bleeding disorders can live their lives without the pressure of having heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), and the concern of postpartum bleeding, thus increasing their QoL [2,5,9,10]. There is a need for a holistic approach regarding care for women with bleeding disorders, not least due to its hereditary nature. Optimal care should include not only adequate medical therapy, but also psychological and social support [7,8,11]. Women who carry the gene for haemophilia A or B have, for example, described feelings of anxiety and guilt for having passed the disease to their son(s) [8,11]. The value of emotional support and genetic counselling is shown to benefit women who carry genetic bleeding disorders such as haemophilia A or B [11].

As nurses working within a coagulation unit, we have the unique opportunity to advise and educate the teenage girls and women who attend. This possibility, our clinical experience and our interest in improving care for women with bleeding disorders that we treat, led us to design a questionnaire for use in our clinic, to explore aspects of being a woman with a bleeding disorder. Our aim was to gain insight as to what extent the women attending our clinic experience HMB, whether they take treatment and/or use other interventions to prevent HMB and how adherent they are to any treatment, and the extent to which they feel or have felt anxiety regarding pregnancy, childbirth and/or family planning.

METHOD

We conducted a questionnaire to gain insight into the life impacts and suspected challenges facing women with bleeding disorders at our coagulation unit. The questionnaire was designed by two nurse specialists working in the Coagulation Unit at Karolinska University Hospital, based on our experience of caring for women with bleeding disorders of varying severities, and was intended to be used purely within this clinical setting. We took into consideration that it should be suitable for women of all ages. In addition to current experiences, we included a “lookback” on teenage years as we often heard from women in our clinic that they had experienced HMB in teenage years. The questionnaire included 18 questions regarding menstruation (n=2), treatment (n=4), impacts on quality of life (n=6), if they have seen a gynaecologist (n=1), have had blood transfusions and/or iron substitute (n=2), other bleeding symptoms (n=2), thoughts about future pregnancy/family planning (n=1) and an open question on anything else regarding their diagnose that they wished to express (n=1).

The first women who answered the questionnaire confirmed, when asked, that there was no lack of clarity in the questions in the questionnaire. Inclusion criteria were that the women were registered with our clinic, aged 16 years or above with a diagnosed bleeding disorder, and able to read and understand Swedish. The women were given the questionnaire during an appointment at our clinic; the questionnaire was self-administered in clinic.

Use of the questionnaire began in 2019 and is ongoing. In this paper, we present results from the first 67 women who were invited to answer the questionnaire. The women included agreed on being part of the results presented. Informed consent was obtained, by way of a signed agreement included with the questionnaire.

RESULTS

All of the first 67 women who were asked to answer our questionnaire agreed to do so. Mean age was 32.5 years (range 16–64 years). Mild von Willebrand disease was the most common diagnosis (n=29; 43.3%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Diagnoses of questionnaire respondents (n=67)

| DIAGNOSIS | N |

|---|---|

| von Willebrand disease | |

| Mild | 29 |

| Moderate | 15 |

| Severe | 3 |

| Haemophilia carrier (haemophilia A or B) | 10 |

| Platelet dysfunction | 4 |

| Glanzmann thrombasthenia | 2 |

| FXI deficiency | 2 |

| FXIII deficiency | 2 |

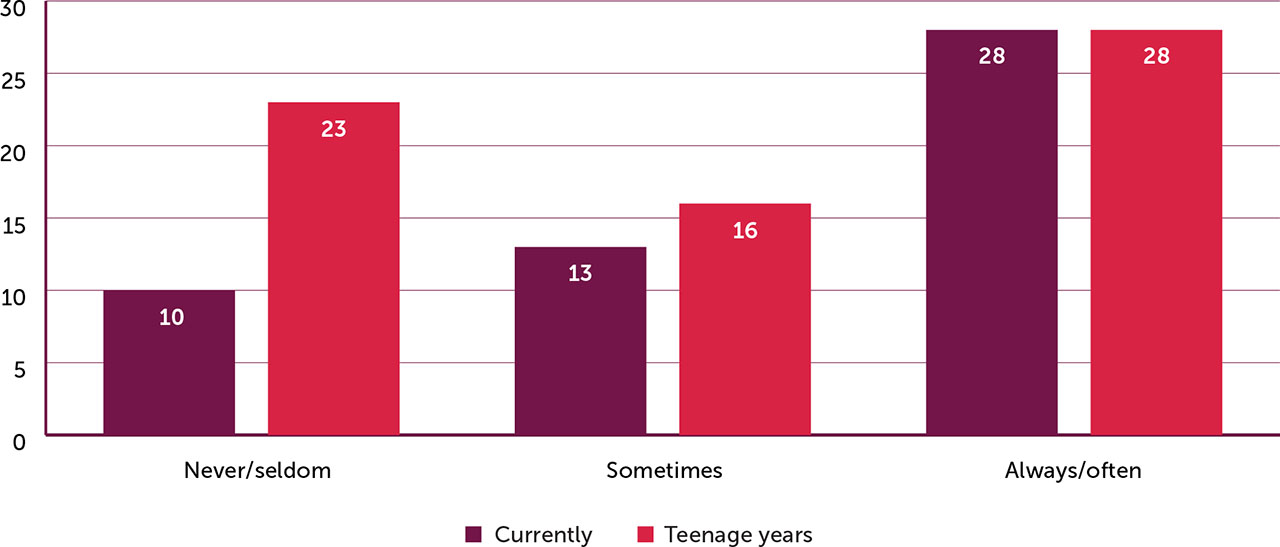

Twenty-five (37.3%) often experience HMB; 18 (26.8%) sometimes experience HMB. The majority (n=51; 76.1%) experienced HMB during their teenage years. Twenty-three (34%) said they seldom took any form of treatment in their teenage years during menstruation (Figure 1). Though most women said they currently take some form of treatment during menstruation, 10 (14.9%) said they seldom do.

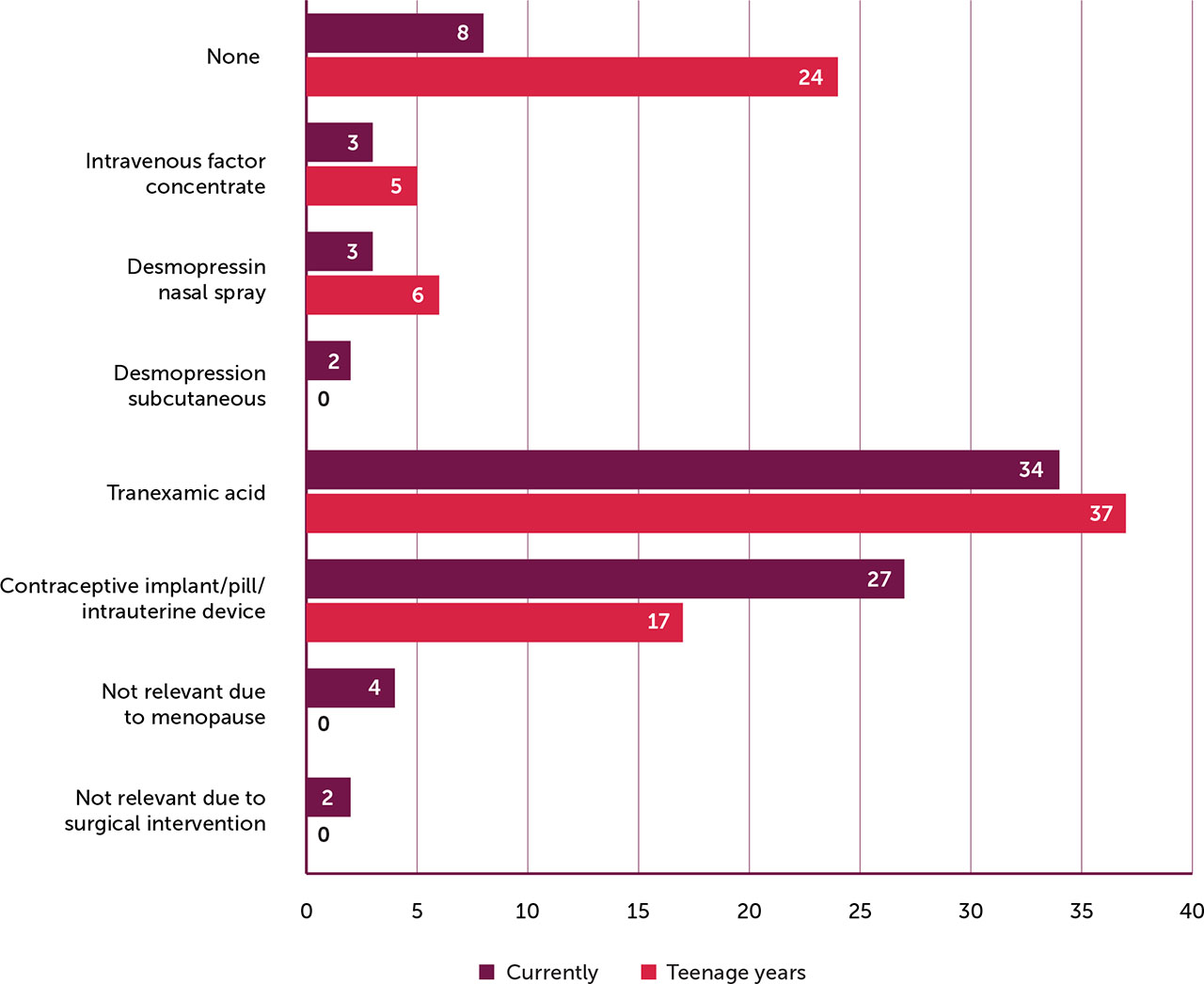

Thirty-four (50.7 %) of the women take tranexamic acid during menstruation and 27 (40.2 %) take a contraceptive pill or have a contraceptive implant or intrauterine device (Figure 2). Eight (11.9%) currently take no treatment during menstruation and 24 (35.8%) took no treatment during their teenage years. Six women (8.9%) do not take treatment due to menopause or surgical intervention (hysterectomy).

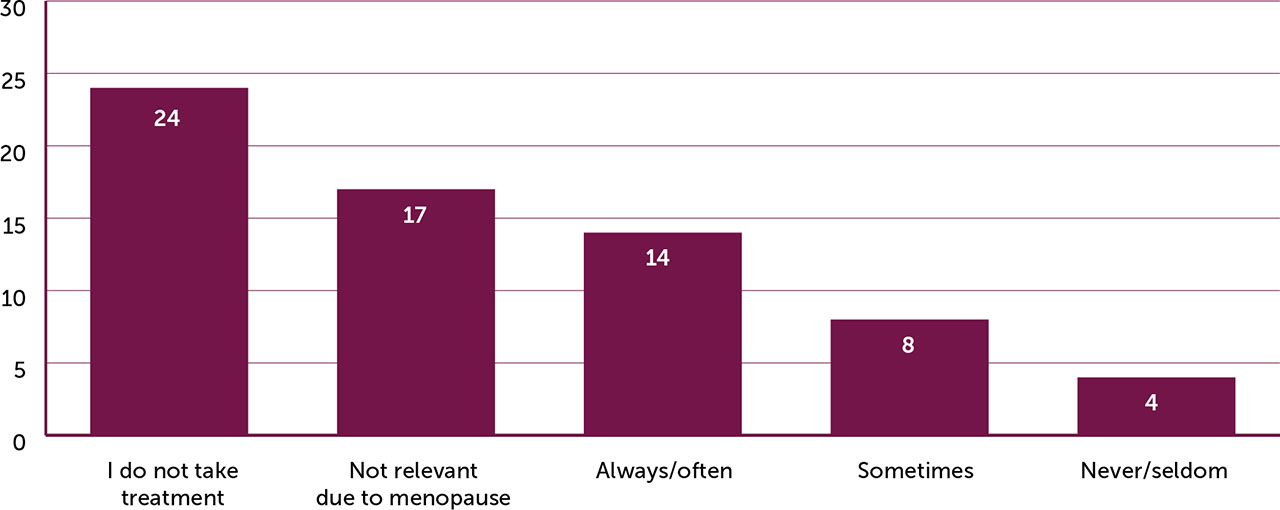

Although more than a third of the women (n=24; 35.8%) said they never/seldon experience HMB when taking treatment, 14 (20.8%) said always or often experience HMB despite taking treatment, and 17 (25.3%) of the women sometimes do (Figure 3).

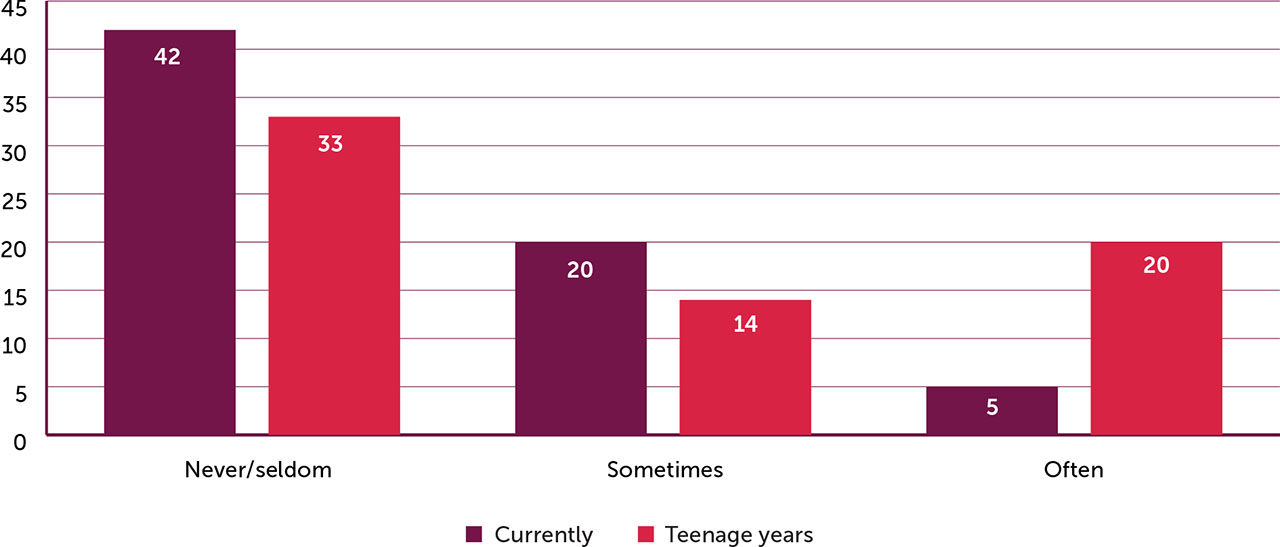

Around two thirds of the women (n=42; 62.7%) said they currently do not experience loss of school/work due to HMB (Figure 4). However, 20 (29.8 %) said they sometimes do and 5 (7.4 %) said they often do.

When asked if their menstruation has a negative impact regarding social relations/activities, for example spending time with friends and family, 22 women (32.8%) answered sometimes and eleven (16.4%) answered often. Thirty-one (46.2%) perceive their menstruation has a negative impact on sexual relationships. Forty-one (61.1%) minimise their level of physical activity during menstruation.

Forty-four (65.6%) of the women have, at some stage, required blood transfusion/s. Thirty-nine (58.2%) said they are anxious or have been anxious regarding future family planning and/or childbirth due to their bleeding disorder.

In addition to menstrual bleeding, over half of the women (n=39; 58.2 %) said they sometimes experience other bleeding symptoms, and 7 (10.4%) said they often do, the most common being bruising and epistaxis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Other bleeding symptoms (n=67)

Question:

| N | |

|---|---|

| Frequency of other bleeding symptoms | |

| Never/Seldom | 21 |

| Sometimes | 39 |

| Often | 7 |

| Localisation of bleeding | |

| Bruising | 38 |

| Epistaxis | 29 |

| Muscular | 2 |

| Joints | 1 |

| Other | 0 |

Thirteen (21.3%) of the women felt that their bleeding disorder had a negative impact on their QoL to a large extent, and 22 (37.3%) that it had a negative impact to a certain extent. Forty-one (61.1%) have had contact with a gynaecologist due to HMB.

Comments from the open question regarding living with a bleeding disorder included the following:

“As a young person I was negatively affected by my bleeding disorder.”

“My menstrual period is long and affects my sex life in an extremely negative way.”

“After having been diagnosed I don’t have any problems or anxiety.”

“All my questions were answered today.”

“I bled a lot at a caesarean and vaginal delivery.”

“I seldom missed school but that is because I attended even though I had HMB. I sometimes didn’t manage a whole lesson without bleeding through.”

“I plan my whole life according to my menstrual period. Why me? Why has nobody ever earlier taken me seriously?”

“Feels scary thinking about future family planning/delivery. I worry about my future children inheriting my bleeding disorder.”

“I went through hysterectomy and I worry about future surgery.”

DISCUSSION

Although the results reported in this paper include a limited number of women with bleeding disorders attending our coagulation unit, they give valuable information and insight into this specific patient group. Most of the women take some form of treatment during menstruation, the most common being tranexamic acid. HMB is experienced by 46% of the women, but 67.3% of them often or sometimes take some form of treatment during menstruation, suggesting that their treatment and/or adherence to their treatment may not be optimised. Some may benefit from adding subcutaneous desmopressin or intravenous factor concentrates to their treatment regimen during menstruation to achieve a better outcome.

During their teenage years, 34.3% of the women who answered the questionnaire did not take any treatment, and 76% remembered experiencing HMB. Our question regarding treatment in teenage years did not clearly clarify that contraceptive implant/pill/intrauterine device is a form of treatment for women with HMB. Furthermore, an unknown number of women in our study may have been diagnosed after their teenage years. Studies show that difficulty in obtaining a diagnosis remains an important obstacle, rooted in lack of awareness and competence amongst non-specialist healthcare professionals [1,7,12]. Even where the diagnosis and treatment of girls with bleeding disorders is improving, women and girls are typically diagnosed with bleeding disorders at a later age than men and boys [5,13].

There are several hormonal measures available for the treatment of HMB, including the levonorgestrel intrauterine system, combined oral contraceptives, progestin or gonadotropin-releasing hormone therapy, with good results in reducing HMB [2,14]. In our study over 40% of the women use some form of hormonal treatment such as contraceptive implant/pill or intrauterine device. This highlights the value of offering adolescents and women with a bleeding disorder the advantage of referral to a dedicated gynaecologist within the multidisciplinary team. In our study, 61.1% of the women have had contact with a gynaecologist due to HMB, hinting at the value of collaboration with the gynaecology team. All specialist bleeding disorder settings should establish and facilitate strong collaboration with their local obstetrics and gynaecology team, including adolescent gynaecology, to improve continuity of care for women and girls with bleeding disorders [1,12].

Over half of the women in our study felt anxiety regarding future family planning and childbirth, clearly suggesting that we need to incorporate routines that address this issue. Offering support, guidance and education, such as genetic counselling, can help individual women gain a greater sense of control over their situation, and reduce the emotional distress associated with being a carrier of a genetic diagnosis [11]. Genetic counselling could be beneficially facilitated by the experienced haemophilia nurse, with the support of the haemophilia team. Nurse-led genetic counselling in inherited diseases has been reported as a positive experience by concerned persons [11]. Studies support that carriers benefit from counselling before considering starting a family [10,11,15,16,17].

Although most of the women reported that they do not experience loss of work or school due to HMB, 25 (37.3%) women reported sometimes or often doing so. Thirty-one (46.2%) said they perceive their menstruation has a negative impact on their sexual relationships,41 (61.1%) reported minimising physical activity during menstruation, and 58.6% feel that their bleeding disorder has a negative impact on their QoL. These findings correlate with earlier and more recent studies, which highlight and describe the importance of improving care and treatment options for women and girls with bleeding disorders, encouraging early diagnosis and adequate treatment and follow-up [2,4,7,14,16,18]. Results from a recent, cross-sectional, nationwide, multicentre study in Sweden showed high levels of HMB and iron deficiency, as well as a substantial loss to follow-up in women with von Willebrand disease, confirming the need for improved long-term care strategies [14]. The same study indicated that more women with type 1 and 2 von Willebrand disease might require von Willebrand factor concentrate to reduce HMB.

Optimised treatment for women and adolescents with bleeding disorders is vital for reducing HMB, and thus improving QoL [1,5,12,13,14,16,17]. They should be managed in specialist bleeding disorder settings, enabling improved personalised care, and supporting better QoL and clinical outcomes [12,15,16,19]. There is also a need to include girls and women in national bleeding disorder registries, thus enabling more co-ordinated data gathering, providing insights into the diagnosis and treatment of girls and women with bleeding disorders [4,5,18].

Given their access to care, we may assume that most women with a bleeding disorder at our coagulation unit are well treated and well educated regarding their diagnosis and treatment. However, results from our questionnaire suggest that there is room for improvement regarding support, education, treatment strategies and follow-up to better treat HMB. All women with bleeding disorders ought to be offered regular follow-up [2,5,11,14].

Our questionnaire provides us with the opportunity, in the clinical setting, to use it as a tool to encourage teenagers and women to take adequate treatment to avoid HMB and to support optimised treatment. The questionnaire is used as part of quality improvement in routine care and is presented to all women with a bleeding disorder at our unit. The insights gained have, for example, led to some teenage girls and women with mild von Willebrand disease or platelet dysfunction to start taking desmopressin subcutaneously at the beginning of their menstrual period, with good results, and some with von Willebrand factor levels in the lower range to administer von Willebrand concentrates intravenously during their menstrual period.

Further studies would be of value to more specifically investigate the treatment regimen of a larger number of women with bleeding disorders, correlated to their diagnosis and level of severity. It may be that women with severe bleeding disorders cope better during menstruation due to more intense follow-up, education and treatment compared to women with milder bleeding disorders.

Limitations and strengths

Our study has some limitations. We did not define HMB; rather, the women responding to the questionnaire made their own conclusions about their menstrual blood loss, potentially under- or over-representing their bleeding symptoms. A number of women (26.2%) said that they do not menstruate due to menopause or other reasons, which were not specified in our questionnaire. To get a clearer picture regarding the group of women who do not menstruate, we would need a more specific question to find out the exact reason, for example to differentiate use of contraceptive implant/pill/intrauterine system or coil, menopause or surgical intervention. We did not have a specific question in our questionnaire to capture age at diagnosis, which may explain the large number of women who recall experiencing HMB in their teenage years. Similarly, late diagnosis (after teenage years or after having experienced childbirth) may have contributed to over 70% of women in our studay having required blood transfusion(s) at some stage.

A further weakness is that our questionnaire is not validated. However, a strength is that it is based on nurses’ expert knowledge and interest in women with bleeding disorders, targeted at improving care in the local, clinical setting. It is designed to help women in this patient group to open up and talk about specific concerns and worries. It could be useful to have a standardised questionnaire for use in all clinical settings caring for girls and women with bleeding disorders, with questions adaptable to the local setting.

CONCLUSION

Many women who responded to our questionnaire experience HMB, a number have had blood transfusion(s), and more than half feel or have felt anxiety regarding future family planning and childbirth. Some do not take treatment to avoid heavy menstrual bleeding. This clearly suggests that we need to incorporate routines that offer support, guidance and education, and which involve gynaecology, obstetrics and genetic counselling.

As health care professionals, we should strive to optimise education, follow-up and treatment for women and girls with bleeding disorders. We need to be aware of the potential physical, emotional and psychological burdens a chronic disease such as a hereditary bleeding disorder can have. The use of our questionnaire in clinic provided a platform to discover these situations enabling the possibility to intervene based on individual needs.