Congenital haemophilia A (HA) is characterised by a lack of factor (F)VIII; those with the severe form have endogenous FVIII levels of <1% [1]. Joint bleeding from HA can lead to arthropathy, which results in pain and functional disability [2,3,4,5]. This, in turn, can impede an individual’s ability to participate in physical and social activities, or engage with school or work [2,6,8], which may influence the quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial health of those affected [1,2,7,9,10].

The standard of care for HA is FVIII prophylaxis, which is associated with reductions in joint bleeding rates and subsequent arthropathy compared with on-demand FVIII replacement [1]. It is also linked to increased participation in educational, professional, and recreational activities, resulting in improved QoL [1]. Despite the benefits of FVIII prophylaxis, the standard and extended half-life options require intravenous administration 1–4 times per week [1,11,12], representing a substantial treatment burden and a related negative impact on QoL [7].

Emicizumab is a humanised, bispecific monoclonal antibody that bridges activated FIX and FX to improve haemostasis [13,14]. It has demonstrated effective bleeding control in numerous clinical trials [15,16,17,18,19,20,21], and is approved for treatment of people with HA (PwHA) of all ages with or without FVIII inhibitors [22]. Emicizumab offers a flexible dosing frequency and is administered subcutaneously [1], which may reduce treatment burden compared with intravenous administration. It is also reported to improve work/school attendance [23] and physical activity, [24] compared with FVIII prophylaxis.

Re-evaluating treatment options can provide benefit to both clinical outcomes and QoL, in addition to enhancing physical and social functioning for PwHA [25]. Treatment re-evaluation can be facilitated by shared decision-making (SDM), which fosters a collaborative dialogue between PwHA and healthcare providers (HCPs). This supports individuals in deciding on treatments that align with their preferences, aspirations, and healthcare needs, by ensuring the person is well informed about the benefits and potential drawbacks of available treatment options [26].

Limited data are available on the day-to-day experiences of PwHA switching to emicizumab treatment, and there is a need for increased understanding of the patient’s perspective to facilitate SDM. This study aimed to describe experiences of switching from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab among participants in the HemiNorth 2 study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants, and the data were analysed using inductive qualitative content analysis [27], which is suited for exploring poorly understood phenomena [28]. The standards for reporting qualitative research (SRQR) were followed throughout the research process [29].

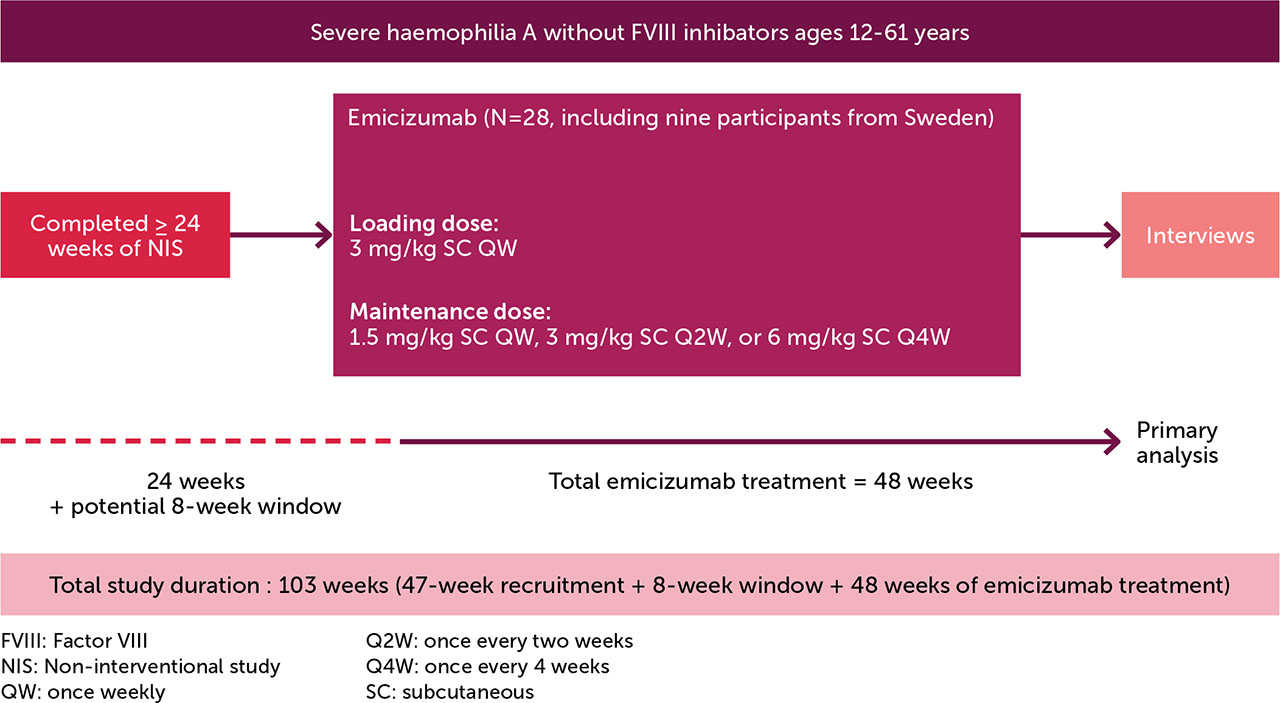

Eligible participants were recruited from the Swedish cohort in the HemiNorth 2 study (MO42245; EudraCT# 2020-003256-32), who had received emicizumab for 48 weeks. The HemiNorth 2 population were rolled over from the HemiNorth non-interventional study ([NIS] MO42590) [30] after receiving FVIII prophylaxis for ≥24 weeks (Figure 1). The NIS included people aged ≥12–60 years, with severe HA, no FVIII inhibitors, ≥1 treated joint/muscle bleed in the 52 weeks prior to enrolment, and a medical need for a treatment change for reasons including, but not limited to, poor venous access, high treatment burden, and/or poor adherence. Most participants in the NIS reported either a moderate or high level of physical activity throughout the study period and experienced a relatively high annualised bleeding rate [30].

Data collection

The interviews were conducted by the first author after the 48-week period of emicizumab treatment; they were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A semi-structured interview guide was used; the main questions were “Tell me about your experiences of switching to a non-factor treatment” and “Tell me about your daily life with haemophilia”.

Data analysis

Data were analysed through inductive qualitative content analysis [27]. Meaningful responses that captured the essence of the participants’ experiences of switching to emicizumab treatment were highlighted and condensed into brief phrases, which were labelled with codes. Throughout the analytical process, findings were discussed amongst the authors to ensure agreement. Trustworthiness was ensured by measures of credibility, dependability, and transferability, as described by Graneheim and Lundman [27].

Ethics

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2022-02191-02). All participants gave their oral and written informed consent to participation and publication of the results. No authors had an HCP relationship with any of the participants. One participant was <18 years old, and his caregiver was present during the interview.

RESULTS

All nine Swedish participants in HemiNorth 2 agreed to participate (Table 1). The mean (standard deviation) age was 33.1 (12.1) years. The open-ended interviews were conducted between March and November 2023 via a teleconferencing system (n=7) or telephone (n=2); the participants chose their preferred format [31]. The interviews had a mean duration of 34 (range: 22–45) minutes.

Table 1.

Demographic and medical data of participants*

The analysis generated three categories and eight sub-categories describing the participants’ experiences of switching from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab (Table 2).

Table 2.

Categories and sub-categories of participant responses

Adapting to a new reality

This category comprised three sub-categories: ‘Learning the new treatment’, ‘The treatment takes less time and space in life’ and ‘New difficulties and different pain’. This category encompassed the changes in daily life involved with adapting to the new treatment; switching treatments demanded the acquisition of new knowledge and skills but also took up less space and time in the participants’ lives.

Learning the new treatment

Switching treatments induced anticipation and anxiety in the participants. They described feeling worried during the first few administrations of emicizumab; this feeling diminished after the initial months of treatment.

Both before and during the switch, participants required guidance on how the medication works, considerations for home treatment, managing bleeds, and recognising potential side effects. Verbal information from HCPs was described as important. The HCPs’ information was trusted, and eased anxiety about the switch; however, it took time to build confidence in, and get accustomed to, the new medication.

“A bit nerve-wracking. There’s always a risk when switching medication. I wondered, will my body respond to this, or will I experience any side effects? When you read through the package inserts and all, you start thinking, ‘Okay! How will I identify these potential side effects if they occur? You start getting a bit worked up and wondering...”

(P8, 31–40 years)

Some participants sought additional information regarding experiences with emicizumab from a patient perspective, via YouTube and other internet platforms; they felt that sometimes the HCP lacked or was unable to convey this perspective.

The treatment takes less time and space in life

Administration was reportedly less time consuming after switching to emicizumab compared with previous treatment. Several participants mentioned they previously found it difficult to locate veins for injections, which was no longer an issue with the subcutaneous route of administration, removing the need for multiple administration attempts. Additionally, emicizumab treatment was more convenient because it was given less frequently and could be administered in the evening, on a fixed day.

“No, I would definitely say it’s less. Partly because it’s a smaller part of the daily routine to take medication. It’s partly much less of a process to take it, you can take it quickly and easily in the evening before going to bed, just once a week.”

(P6, 21–30 years)

Some participants had previously been bothered by bruises and scars from venous injections on the backs of their hands and the crooks of their arms. After switching, the scars began to fade, and the disease felt less visible to others.

Although some reported that the treatment took less time and space in their daily lives; others stated they did not notice much difference, finding neither FVIII prophylaxis nor emicizumab treatment burdensome.

New difficulties and different pain

All participants described switching to subcutaneous administration as an adjustment, with many highlighting unfamiliarity with varying the injection site. All participants felt that taking the medication was painful; the needle caused discomfort when piercing the skin, and they were caught off guard by this. They also highlighted the technical difficulty in keeping the needle stable when administering emicizumab.

A feeling of normality

This category included three sub-categories: ‘Changed situation in professional life’, ‘New prerequisites for physical activity’ and ‘Hope for the future’. In this category, enhanced feeling of normality, general health, and hope among the participants was emphasised.

Changed situation in professional life

Some participants described a transformation in their professional lives after switching, particularly individuals engaged in physically demanding occupations. The necessity to explain their condition to colleagues and the resulting impact on work diminished considerably, which was compounded by fewer work absences. A newfound sense of normalcy at work was described, and the novel experience of blending in with peers was highlighted.

“I can recover a little faster, work more efficiently now than I did before... it’s like, for example, I’ve nailed frames and such and nailed a staple into my thumb. I just removed it. It wasn’t stuck in too deeply, but it was in there. If I had been on the other medication, I would’ve had to go home. Now, I just put on a bandage or wrapped it up a bit, and after a day or so, it was fine again. I could still work.”

(P2, 41–50 years)

Those with less physically demanding occupations described no impact on their professional lives after the switch, although they noted that haemophilia had little influence on their professional lives when being treated with FVIII prophylaxis.

New perspectives on physical activity

Participants reported that the change in treatment enhanced their physical activity and reduced the need to schedule training and physical activities around treatment days. A newfound sense of spontaneity and freedom to engage in activities at will was prevalent; however, this did not always translate into increased physical activity. Instead, there was a shared emphasis on preserving a sense of normalcy, for which the ability to engage in physical activities was a significant contributor.

Some participants expressed newfound confidence in physical activity and training, with less associated joint pain. It took a few months after switching before the pain lessened, and it was mainly reported by participants with previous joint damage.

Hope for the future

The non-factor treatment greatly improved the participants’ hope for future advancements in haemophilia treatment, which some had reportedly lost before. With the new treatment, they dared to look forward and envision continued development and treatment of the disease.

As the disease took less time and space in daily life, feelings of improved health emerged, with no visible needle marks on arms and hands, reduced sick leave, fewer bleeds, and a positive outlook on the future. A few participants described their family members and other people around them perceiving them as more energetic and happier after switching. Relatives and friends shared in the participants’ joy over the positive change.

“You feel like, well, how can I put it? It’s like being born again, you could say.”

(P2, 41–50 years)

Previously, some participants engaged in challenging physical activities, such as long hikes or climbing mountains, against advice from family members and HCPs, to “defy” the disease and prove it did not hinder or define them as individuals. After the treatment change, they participated in these activities simply because they wanted to.

Shattered expectations

This category included two sub-categories: ‘The disease persists’ and ‘The difference may not be significant’, which underlined that not all expectations of the new treatment were fulfilled. The participants realised that their physical injuries were still present, and that the disease still impacted their lives.

The disease persists

Hopes for the benefit of emicizumab were high before the switch. Some time after switching, participants came to realise that their existing physical injuries would persist. The movement restrictions remained, and the disease was still part of their lives. The pain had diminished but was still present for those with pre-existing joint damage; the realisation that joint pain would not completely disappear was disappointing. Some expressed concern about microbleeds and the long-term damage these might cause. In some cases, participants perceived the bleeds on emicizumab differently compared with those on FVIII prophylaxis; they were seen as superficial, small bleeds that were harder to stop.

The difference may not be significant

A number of participants discussed career aspirations they had been unable to reach due to haemophilia. With the new treatment, those dreams were revived. However, participants were disappointed to learn that emicizumab did not mitigate all the fundamental limitations in their professional lives.

Participants described fewer bleeds, although some bleeding persisted. Concerns around additional FVIII treatment, and when this was required, were common, with an expressed need for more knowledge on this. Some participants did not notice any difference in bleeding after the switch; they were satisfied with the bleed protection conferred by both FVIII concentrate and emicizumab.

DISCUSSION

These results revealed that switching from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab increased the feeling of normality, with the disease taking less time and space in the participants’ daily lives. Previous quantitative studies reporting on the experiences of PwHA who switched from FVIII prophylaxis to emicizumab, as measured by patient-reported outcome measures, reported reduced burden of treatment with emicizumab [32,33], which aligns with the results of this study. Qualitative data on participants’ experiences in switching to emicizumab further substantiate these findings, with respondents attributing reduced burden to lower administration frequency for emicizumab, as well as the shorter subcutaneous administration time [34]. However, it is important to note that the cited data were collected in people with FVIII inhibitors, who often face different treatment burden challenges compared with people without FVIII inhibitors [35].

The impact of HA on employment has been extensively reported [2,6,7,8], and is reiterated in the current study. Despite the short study period, most participants reported improvements in their professional lives following the switch, quoting fewer work absences as a contributor to this. Improvements in professional life following emicizumab initiation have been similarly observed in other studies [18,23,24]. Most of the participants here articulated a newfound ‘normality’ in their professional lives. A previous study investigating the employment of young adults with HA found 25% of 230 respondents reported that nobody at their workplace knew about their HA, and 37% reported that only a few knew [6]. This underscores the desire for many PwHA to fit in with their peers, which is echoed in this analysis.

Participants felt that the treatment change allowed them the freedom to perform physical activity at any time they wished. They also felt less fear of pain after physical activity. Despite this, their physical activity levels did not increase after the switch. This suggests that the physical activity of PwHA is partly influenced by factors other than bleed protection and pain; these could include independent motivation, peer influence, or access to support systems encouraging physical activity [36].

Some participants expressed disappointment that emicizumab treatment did not live up to their expectations, particularly in those with pre-existing injuries. Previous research indicates that alternative prophylactic treatments, including emicizumab, may not alleviate all aspects of haemophilia, especially when joint damage has already occurred [37,38], and additional research into experiences with switching to emicizumab corroborates this [34]. It is essential for HCPs to have open discussions with individuals considering emicizumab when engaging in SDM, ensuring they have a clear, realistic understanding of what to expect regarding joint pain and pre-existing injuries before making the transition to alternative prophylaxis.

The results indicated that knowledge on how the medication functions in the body and how to manage bleeding episodes was lacking in some cases. Some interviewees reported not knowing when it was appropriate to administer FVIII concentrate for a bleed, which has also been expressed in previous experiences with emicizumab [34]. This gap in communication suggests the need for improved education and more comprehensive discussions between PwHA and HCPs to ensure clarity around the new treatment. All participants described difficulty adjusting to the initial pain and technical difficulty associated with subcutaneous administration of emicizumab. This has also been reported in another study at a single Haemophilia Treatment Centre, in which 13% of participants listed subcutaneous injections as a knowledge gap when switching [39]. People initiating emicizumab may have only a few appointments with their HCP to learn to administer the treatment, compared with weekly meetings over multiple months when learning to administer intravenous treatment. While this may reduce healthcare resource utilisation, it could also limit opportunities for patient education and support. Our results suggest that people initiating emicizumab treatment may benefit from tailored discussion and more follow-up visits, offering them greater opportunity to learn how to manage their new treatment. This approach can help ensure that they feel supported and empowered to make informed decisions on their care. Some participants felt they lacked insights from a patient perspective. To address this, HCPs could refer individuals who are considering switching to emicizumab to patient advocacy groups. These groups can offer educational resources specifically designed to meet the needs and understanding of PwHA, potentially enhancing the SDM process [40]. In a previous report investigating patient perspectives on novel treatments, respondents also listed magazines and social media as sources of information; the latter was reportedly useful for exchanging experiences with peers. However, participants also reported difficulty in knowing what to search for, and how to find information that was relevant to their specific situation [41].

Limitations

Participants were recruited from the Swedish cohort of the HemiNorth 2 study, meaning that they may not be representative of the whole HA population, although they did represent the entire Swedish population of the study. All participants were ≤45 years of age, meaning that older participants with a potentially greater disease burden were not represented. Additionally, the results reflect the initial 48 weeks of emicizumab treatment; further research is needed to capture the long-term experiences of PwHA being treated with emicizumab. The results of this study should be viewed as one interpretation that contributes to a broader understanding of the treatment-switching experiences of PwHA.

CONCLUSION

Our study findings convey reduced disease burden in PwHA switching to emicizumab, as well as a newfound sense of normality and hope for the future treatment of haemophilia. These experiences also highlight gaps in knowledge about emicizumab among PwHA, and unrealistic expectations in those with joint damage and pre-existing injuries; addressing these issues is a necessary step in ensuring optimal SDM practice and managing expectations when switching treatments.