It is estimated that 254 million people are living with hepatitis B and 1.2 million were newly infected in 2022 [1,2]. In sub-Saharan Africa, robust epidemiology data are lacking. There are striking differences in seroprevalence by country and by region [3]. Approximately 70–95% of adults demonstrate evidence of past exposure to hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection [3,4]. Seroprevalence based on hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity is estimated to range between 6%–20% [5]. In 2015 the estimated prevalence of HBV in South Africa, based on 18 studies was 6,7% [4]. HBV infection is commonly seen in black South Africans. The prevalence ranges from 2.7%–16% in males and females residing in rural and urban areas [6].

During chronic HBV infection the interaction between the virus and host is dynamic and the phases of chronic HBV vary between overt and occult infection [7]. Overt infection is characterised by detectable HBsAg in serum, whereas occult infection is defined as the absence of detectable HBsAg in serum in the presence of replication competent HBV DNA in hepatocytes. Occult HBV infection (OBI) is classified into two groups based on the presence or absence of hepatitis B core (anti-HBc) and hepatitis B surface (anti-HBs) antibodies. Seropositive OBI is anti-HBc and anti-HBs positive. Seronegative OBI lacks both antibodies [8]. Performing liver biopsy routinely in clinical practice is not possible; therefore, the diagnosis of OBI is based on the detection of low levels of HBV DNA in serum [8,9]. The exact pathogenesis of OBI is not fully defined. However, mutations producing modified HBsAg types and suppressing HBV replication through epigenetics are postulated [7,8,9]. It has been demonstrated that the viral genome of HBV can persist indefinitely in previously infected HBsAg-negative individuals [10]. The clinical significance of OBI is related to the risk of HBV transmission and potential reactivation in patients who become immunocompromised [7,8].

The prevalence of OBI varies significantly across the globe, with higher rates being reported in Asia [11]. The rates need to be interpreted with caution as they are dependent on cohort characteristics, HBV endemicity, and methods used for diagnosis [12]. In blood donors, occult HBV infection prevalence mirrors HBV endemicity and in high-risk groups occult HBV infection prevalence is substantial, irrespective of endemicity [13]. Detection of OBI can be missed in blood donors despite the screening and nucleic acid testing [14]. As a consequence, HBV transmission through blood donors remains a potential risk [14,15].

Haemophilia is an X-linked recessive hereditary bleeding disorder characterised by reduced levels or complete deficiency of specific coagulation factors. Modern management of people with haemophilia (PWH) includes regular replacement therapy with standard and extended half-life coagulation factor concentrates. In the South African context, plasma-derived clotting factor concentrates are still the most frequent products used. The lyophilised concentrates are produced from large plasma pools. Potential threats to PWH are transfusion-transmissible viruses including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV). Several patients who received infusions of plasma-derived factor VIII or factor IX concentrates, acquired HCV and HIV in the 1980s [16]. These infections were mostly from blood products imported from the United States of America (USA), where donors were remunerated. The United Kingdom (UK) Infected Blood Inquiry report was recently released to parliament [17]. The introduction of deferral of high risk donors, individual donor nucleic acid testing and viral inactivation procedures have virtually eliminated the risk of viral transmission by plasma derived products [18]. Safety measures in the form of anti-HBV vaccination, together with virally inactivated products were introduced in 1995 and 1991, respectively.

In South Africa, the molecular characterisation of OBI has been reported in blood donors, HIV co-infected and haemodialysis patients [19,20,21]. A few global reports have addressed the prevalence and significance of OBI in PWH [22.23.24.25]. In these reports, prevalence ranges from 0%–52.1% showing huge disparity. As a country with relatively higher endemicity of HBV, the description of the prevalence of OBI in haemophilia patients in South Africa will better inform the diagnostic methodologies currently utilised for yearly surveillance of patients receiving plasma-derived products.

Effective vaccination against HBV remains the mainstay of hepatitis B prevention. In May 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted the first “Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016–2030”. The strategy highlights the critical role of Universal Health Coverage and the targets of the strategy are aligned with those of the Sustainable Development Goals. The strategy has a vision of eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health problem and this is encapsulated in the global targets of reducing new viral hepatitis infections by 90% and reducing deaths due to viral hepatitis by 65% by 2030. Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa are in the process of developing plans to achieve this goal. Access to affordable diagnostic assays that identify individuals infected with HBV remains one of the challenges [26].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient recruitment and sample collection

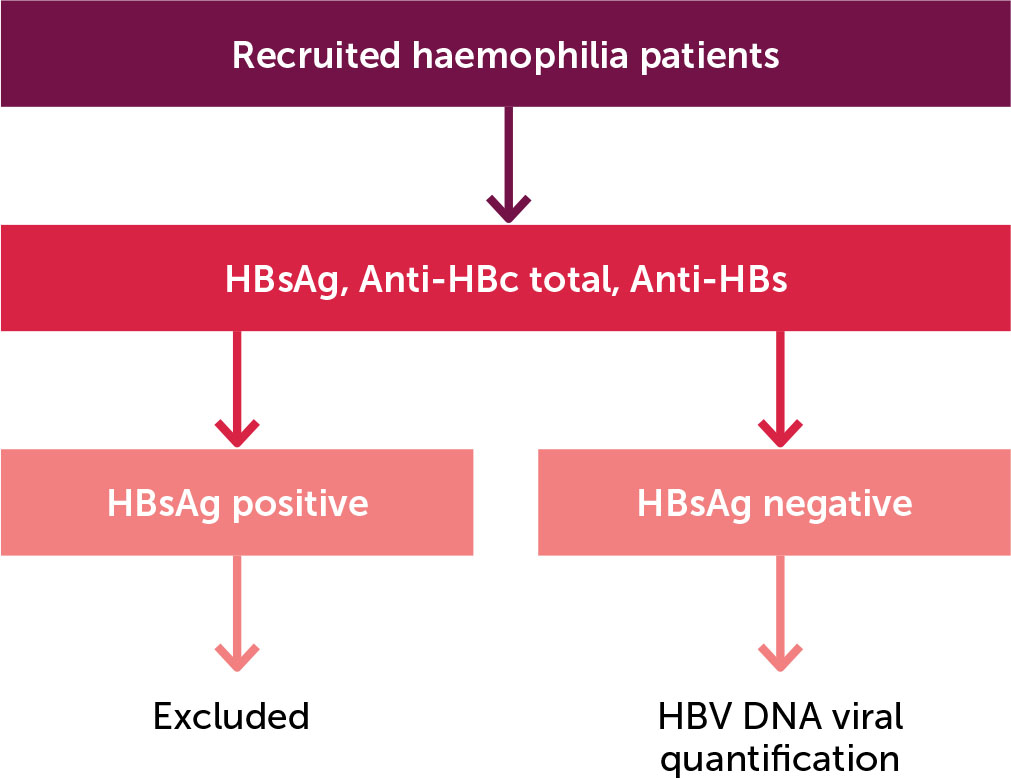

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted across three haemophilia treatment centres in South Africa’s Gauteng Province between April 2022 and October 2023.The study population consisted of haemophilia A and B patients attending the haemophilia treatment centres at Steve Biko Academic Hospital (SBAH), Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH) and Dr George Mukhari Academic Hospital (DGMAH). Figure 1 shows a diagram outlining participant recruitment, inclusion and exclusion. Patients younger than 13 years of age and those who demonstrated HBsAg positivity on serology testing were excluded. The personnel involved in this study are responsible for the management of adult patients with haemophilia. In our healthcare facilities, the official age cut-off for paediatric patients is 12 years, which defines the study population. The specific products used for factor replacement were not included in the study’s selection criteria.

Figure 1.

Diagram outlining participant recruitment

HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen

Anti-HBc: Anti-hepatitis B core antibodies

Anti-HBs: Anti-hepatitis B surface antibodies

This study was designed and performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional research ethics boards of the respective institutions, amongst them, the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pretoria, (protocol no. 12/2022).

Laboratory methods

Serology

Serological testing of HBV markers was performed at the diagnostic laboratories of the collaborating centres. Plasma samples from all patients were tested for the presence of HBsAg, total anti-HBc and anti-HBs using IVD assays on the Abbott Architect platform (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, United States). In addition to HBV serology tests, HIV serology, HCV IgG serology and FVIII and FIX inhibitors were also performed as part of patient management. The cut-off value of anti-HBs was set at 10 mIU/mL, and titres lower than ten were considered as not immune. Patient plasma samples were kept at 2–8 degrees Celsius and the serology testing was undertaken within 48 hours of blood collection.

Real-time HBV DNA polymerase chain reaction quantification

Blood samples were collected into plasma preparation tubes. Plasma was separated and frozen at −20 degrees until analysis. HBV DNA viral quantification was performed on all HBsAg-negative plasma samples using the Abbott Alinity m analyser. (Abbott Laboratories, Illinois, United States) The assay targets and detects HBV genotypes A and H. The analytical range of the assay is 4.29 IU/mL to 1000 000000 IU/mL with a lower limit of quantification of 10 IU/mL.

RESULTS

In total, 66 male PWH were included in the study. Brief haematological and demographic information of the patients is presented in Table 1. The patients’ ages ranged between 13 and 73, with a median age of 29. Haemophilia A and haemophilia B were diagnosed in 59 (89.4%) and 7 (10.6%) of the recruited patients, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

Serology results are shown in Table 2. Fifty-six of 66 (84.9%) patients had a history of complete vaccination schedule against HBV. Ten vaccinated patients were non-responders with anti-HBs titres of less than 10 IU/ml. In total, there were five patients who were found to be positive for anti-HBc indicating natural exposure to HBV infection. All these patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Serology results of study participants

A total of 5 (7.6%) were HIV seropositive. All were vaccinated against HBV, with two patients being vaccine non-responders. They were all HBsAg negative with no anti-HBc antibodies.

A total of 49 (74.2%) of our patients were born before 2005, with more than half of them born before 1995. None displayed serological or molecular evidence of OBI.

The lower detection limit for Alinity m HBV is 10 IU/Ml in plasma for HBV genotype A, which is the predominant HBV genotype in South Africa [11]. The PCR results showed that none of the patients had the target DNA detected. This finding rendered the point prevalence of OBI to be 0% in this cohort.

DISCUSSION

We found a 0%-point prevalence of OBI in our cohort of PWH in the Gauteng province of South Africa. It is comparable to others that have reported OBI in haemophilia patients that range from 0% −51.2% [22,23,24,25]. The group from Japan that reported a high rate of 52.1% HBV DNA positivity is an outlier [23]. The observed differences are multifactorial, including studied population HBV endemicity, sampling and testing methodologies.

The intermediate pure plasma derived factor VIII (Haemosolvate) and the prothrombin complex concentrate (Haemosolvex) were introduced into South Africa in 1990 and 1991, respectively. The plasma used in the production of both products is mainly sourced from the South African National Blood Service (SANBS). South Africa introduced universal HBV vaccination for newborns into the expanded immunisation program in 1995. Individual donation nucleic acid testing was only introduced in 2005 as a screening tool [27]. Based on this information, patients who received factor concentrates before these interventions would have been at a theoretically higher risk of acquiring OBI. This implies that the viral inactivation procedure that the National Bioproducts Institute (NBI) utilises in manufacturing these products from pooled fresh plasma is effective. The company uses solvent detergent reagents polysorbate and tri-n –butyl phosphate[28].

Our findings demonstrate a low prevalence of occult hepatitis B infection among PWH, reflecting the effectiveness of current blood safety protocols, vaccination programs, and viral screening measures. This supports continued confidence in local transfusion and clotting factor concentrate manufacturers. Confidence in viral safety may help promote broader adoption of prophylactic clotting factor replacement, which remains suboptimal in some settings. All participants in our cohort are exclusively receiving clotting factor replacement therapy. Unfortunately, prophylaxis is not yet fully established as the standard of care in our setting, and some of the patients are managed with episodic treatment. The incorporation of molecular testing into annual screening would not be cost-effective given the current risk profile. Previous blood transfusions, high-risk sexual behaviours, and illicit injectable drug use were not assessed in our cohort. Vaccination has been demonstrated to be effective regardless of the mode of hepatitis B transmission. The risk of blood borne infections within our cohort is comparable to that of the general population

The different platforms that are used for HBV DNA testing demonstrate different sensitivities. The latter may contribute to the observed differences among the haemophilia OBI studies. The experts at the OBI workshop in Taormina in October 2018 recommended using highly sensitive nested PCR or real-time PCR assays that can detect fewer than ten copies of HBV DNA for the diagnosis of OBI [9]. Our analysis was performed on the Abbott Alinity m HBV assay, which has a documented limit of quantification of 10 IU/ml. Our method is sufficient for the detection and quantification of HBV DNA in plasma. No information is provided on the platform utilised by the Japanese group that reported a prevalence of 52.1%. Varaklioti et al. used a more sensitive method than our laboratory [24].

Limitations

The presence of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) that is fully replication-competent is essential for the diagnosing OBI. Occult HBV DNA may be intermittently detected in plasma [7,29]. Therefore, serial sampling is ideal. It was not possible to undergo this exercise in our study. None of the publications that looked at haemophilia cohorts report serial sampling, which constitutes a limiting factor for the study.

The study cohort included all current adult haemophilia patients managed in the main haemophilia treatment centres in Gauteng, South Africa who met the inclusion criteria. This provided a valuable snapshot for the burden of disease in this part of the world. A larger multi-centre study would provide sufficient power for generalisability.

CONCLUSION

None of the 66 patients with haemophilia, from three haemophilia clinics in Gauteng, demonstrated molecular evidence of occult hepatitis B in blood. Our finding of 0% detection of OBI in PWH needs to be interpreted in context. There still remains a potential risk of failure to detect OBI in all blood donors of up to 0.4 as found by Weusten et al. [14].