Acquired haemophilia A (AHA) is a rare autoimmune disorder caused by neutralising autoantibodies against endogenous factor VIII (FVIII), resulting in spontaneous and often severe bleeding episodes. AHA predominantly affects the elderly, with a median age of 75 years [1]. While the aetiology is often idiopathic, it can also be triggered by factors such as malignancy, autoimmune diseases, infection, or medication. Approximately one to five per cent of cases occur in females during pregnancy or the postpartum period [1,2].

The management of AHA necessitates a dual approach. Immediate control of acute bleeding is achieved through haemostatic therapy using either bypassing agents (BPAs), such as recombinant activated FVII (rFVIIa), activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC), or porcine FVIII [2]. Simultaneously, long-term eradication of the inhibitor is pursued through immunosuppressive therapy [2]. The chance of achieving complete remission or experiencing relapse depends on various factors, with FVIII activity level below 1 IU/dL playing a significant role [3].

Although BPAs are highly effective in treating bleeding episodes, they are rarely used for long-term prophylaxis (i.e., to prevent bleeding) due to their short half-life, the burden on patients requiring frequent intravenous infusions, and the high associated costs [4,5]. Additionally, the intensive use of BPAs is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events. As a result, nearly 60% of patients experience recurrent bleeding before achieving partial remission (FVIII activity level >50 IU/dL) [6]. For patients with AHA, mortality rates are especially high due to infections related to immunosuppressive therapy [1,7]. Consequently, finding a balance between minimising bleeding risk through rapid inhibitor eradication and mitigating treatment-related side effects is challenging, especially in the elderly and frail population [7].

With this in mind, recent investigations have explored whether emicizumab could be used as prophylaxis in AHA patients to prevent recurrent bleeding and potentially delay or reduce the intensity of immunosuppression. Several case reports and recent studies, such as the GTH-AHA-EMI study and AGEHA study, have shown promising results with emicizumab effectively reducing bleeding episodes [4,8,9].

Despite these encouraging results, concerns remain about the thromboembolic risk associated with emicizumab, as well as uncertainties regarding the long-term effects of untreated autoantibodies that would typically require immunosuppressive therapy. The aforementioned studies reported thrombotic events in only 4% to 8% of cases [4,8,9]. However, they excluded higher-risk patients, such as those actively being treated for thromboembolic complications – which is a common scenario in the elderly population [4,9]. Furthermore, an increased thromboembolic risk was identified in patients with congenital haemophilia A and elevated cardiovascular risk [10]. Another limitation of emicizumab is its inability to treat acute bleeds, which still require BPAs. In addition, combining aPCC with emicizumab should be avoided due to the risk of thrombotic microangiopathy [11].

Given these concerns, it is crucial to tailor treatment to each individual patient with AHA. These cases are often complex, requiring a personalised approach to determine the most appropriate treatment strategy. In this case series, we aim to highlight the complexity of AHA management through three cases, each presenting unique challenges and considerations.

METHODS

All three patients were treated at the Hemophilia Treatment Center Nijmegen-Eindhoven-Maastricht between 2020 and 2023. All included patients provided informed consent for publication of their clinical information. Laboratory results presented were obtained during regular diagnostics, including FVIII activity levels (one-stage) and inhibitor titres (Nijmegen Bethesda Assay). Assays were conducted following standard diagnostic procedures.

RESULTS

Case 1

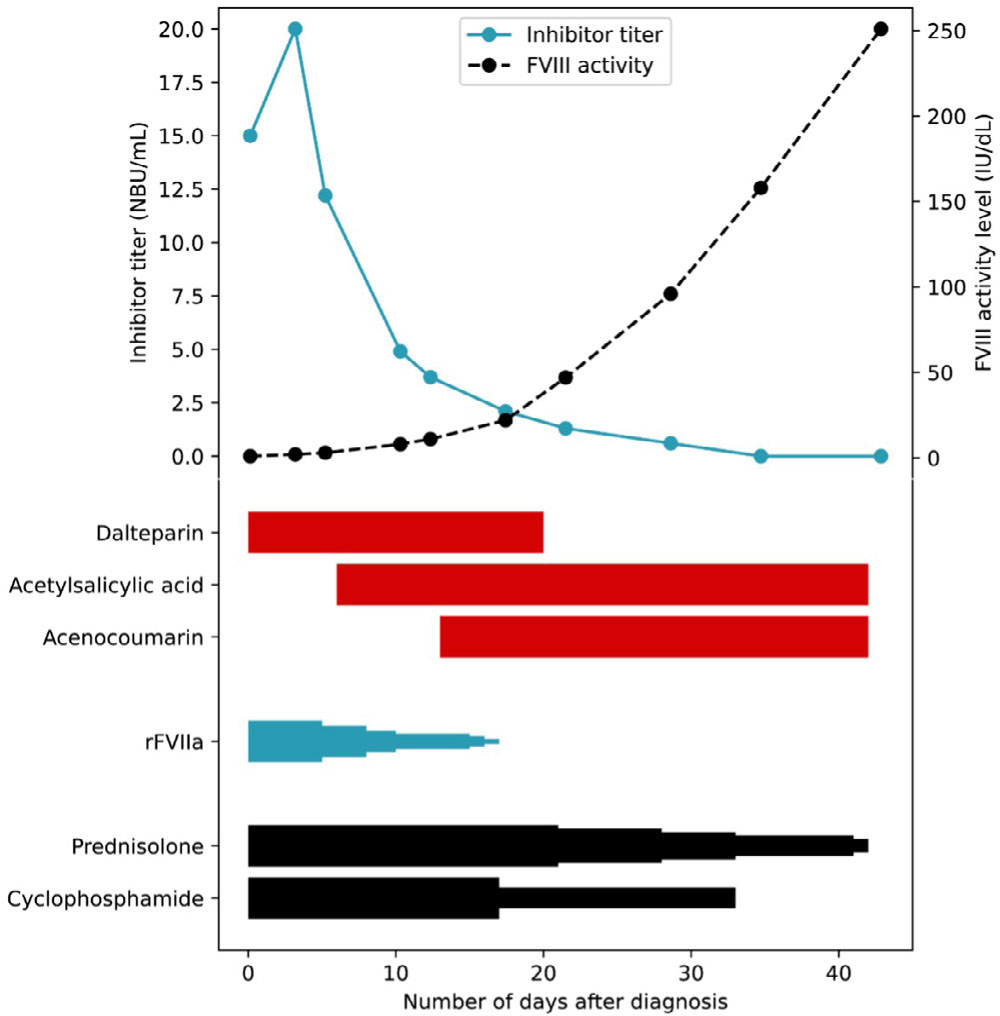

A 58-year-old woman presented with extensive haematomas on her arms and legs, as well as minor haematomas on her face and in her oral cavity, without any preceding trauma. Her medical history included systemic lupus erythematosus and extensive cardiovascular issues, such as a mechanical tricuspid valve. She had undergone an endovascular aortic repair procedure for an abdominal aortic aneurysm two months prior to presentation. She was receiving treatment for these conditions, including prednisolone, acenocoumarin, and acetylsalicylic acid. A high titre FVIII inhibitor of 15 NBU/mL was found, with a subsequent FVIII activity level of <1 IU/dL (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The course of the inhibitor titre and factor VIII activity level in Case 1, alongside the tapering schedule of haemostatic and immunosuppressive therapy.

Each narrowing in the graph represents a dose reduction step. Acenocoumarin was started according to the loading regimen, and subsequently dosages were adjusted based on the International Normalised Ratio (INR).

FVIII: factor VIII

rFVIIa: recombinant activated factor VII

The patient was diagnosed with AHA, most likely triggered by the underlying systemic lupus erythematosus and recent endovascular surgery. To eradicate the inhibitor, her initial prednisolone dose was increased to 1 mg/kg/day, and cyclophosphamide (50 mg twice/day) was initiated. rFVIIa was started at 90 μg/kg eight times/day. Acenocoumarin and acetylsalicylic acid were temporarily discontinued, and dalteparin was initiated at 12,500 IU/day (Figure 1).

Case 2

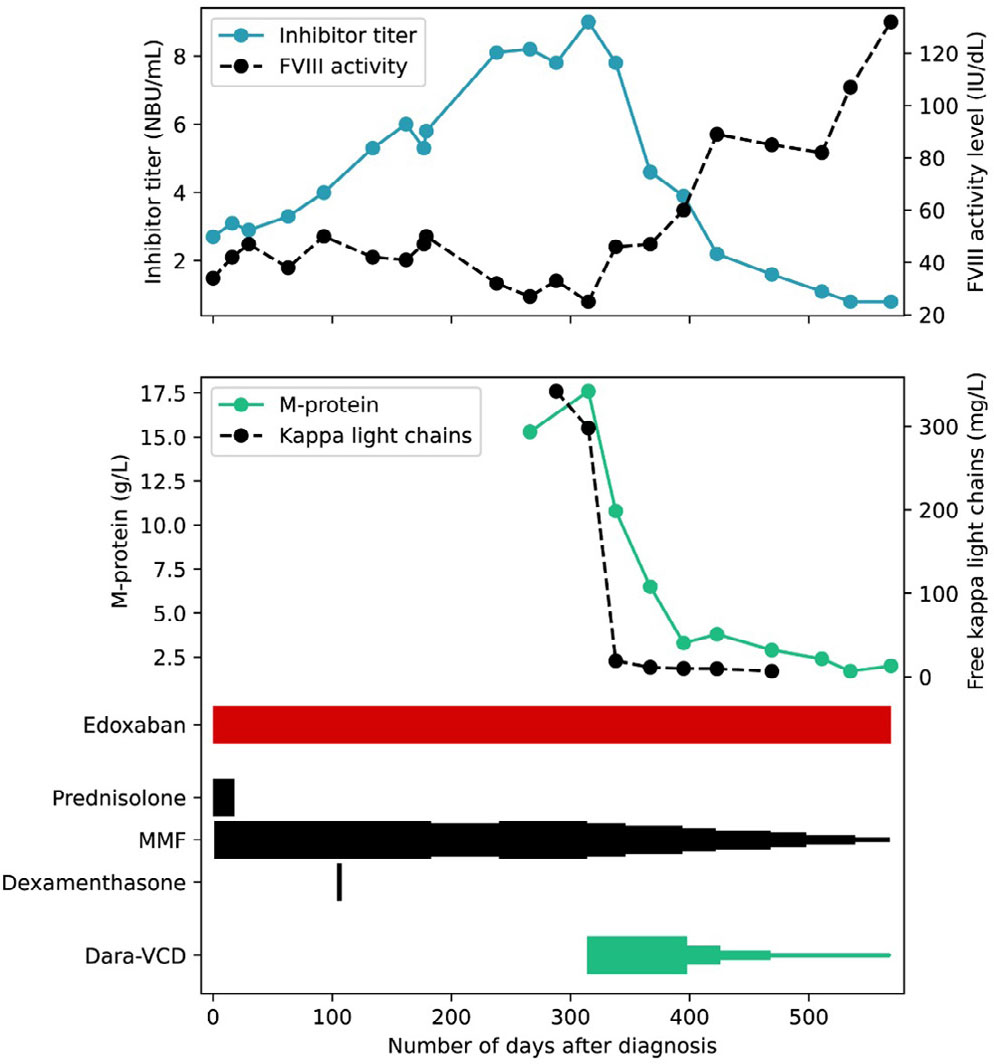

A 73-year-old woman, diagnosed with atrial fibrillation and subsequently treated with edoxaban, had been undergoing outpatient follow-up for eight years due to AHA without a clear underlying cause. Multiple attempts to induce remission with immunosuppressive therapy were unsuccessful. During follow up, the FVIII activity level decreased to 34 IU/dL, while her inhibitor titre increased to 2.7 NBU/mL (Figure 2). Consequently, immunosuppressive therapy was restarted. Due to previous side effects from prednisolone, a low dose of 0.5 mg/kg was prescribed. Additionally, treatment with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; 1000 mg two times/day) was initiated (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The course of the inhibitor titre, factor VIII activity level, M-protein, and free kappa light chains in Case 2, alongside the tapering schedule of immunosuppressive and chemotherapy.

Each narrowing in the graph represents a dose reduction step.

FVIII: factor VIII

MMF: mycophenolate mofetil

Dara-VCD, daratumumab-bortezomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone

The inhibitor titre continued to rise and dexamethasone pulse therapy was started. Diagnostics were repeated to explore a potential underlying cause. Laboratory tests revealed an elevated IgG M-protein (15.3 g/L). Subsequent analyses showed a level of free kappa light chains of 342 mg/L, and the bone marrow exhibited 20% monoclonal plasma cells. On computer tomography, a thoracic lytic lesion was identified, leading to the diagnosis of multiple myeloma.

Considering her age and the concomitant diagnosis of AHA, treatment with daratumumab-bortezomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone was initiated. Concurrently, treatment with MMF 1000 mg twice daily was continued as specific AHA treatment (Figure 2). At the initiation of therapy, the FVIII activity level was 25 IU/dL, and the inhibitor titre was 9.0 NBU/mL. Within 23 days, an increase in FVIII activity level was observed to 46 IU/dL alongside a decrease in inhibitor titre to 7.8 NBU/mL.

Case 3

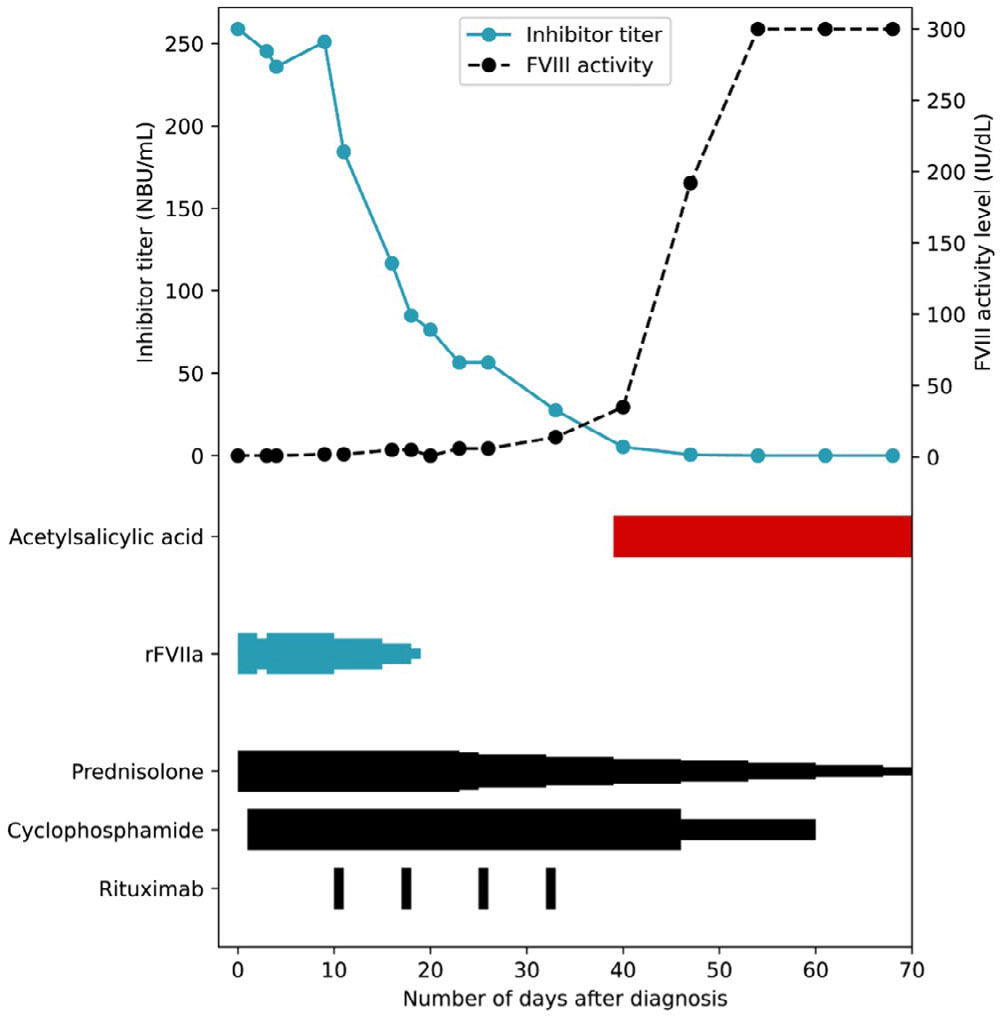

A 70-year-old man was admitted to the hospital due to the spontaneous development of haematomas and muscle bleeds. His medical history included decompensated heart failure resulting from a myocardial infarction, for which he underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Additionally, he had remitting seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting edema (RS3PE), a rheumatic disease. His medication included, among others, acetylsalicylic acid. At the time of presentation, his FVIII activity level was <1 IU/dL, with a subsequent inhibitor titre of 258.8 NBU/mL (Figure 3). Consequently, the patient was diagnosed with AHA. No underlying condition was identified other than his rheumatic disease.

Figure 3.

The course of the inhibitor titre and factor VIII activity level in Case 3, alongside the tapering schedule of haemostatic and immunosuppressive therapy.

Each narrowing in the graph represents a dose reduction step.

FVIII: factor VIII

rFVIIa: recombinant activated factor VII

Treatment with prednisolone 1 mg/kg and cyclophosphamide 50 mg twice daily was initiated. Due to suspicion of active bleeding, rFVIIa was initiated at 90 μg/kg eight times/day, and acetylsalicylic acid was temporarily discontinued. Given the lack of response to immunosuppression, rituximab was initiated on day 12, resulting in a decrease of the inhibitor titre and increase in FVIII activity level. This allowed for a reduction in dosing of rFVIIa (Figure 3). The patient achieved complete remission on day 47, and simultaneously, the FVIII activity rose to supranormal levels (FVIII >300 IU/dL).

DISCUSSION

Recently, the use of emicizumab in patients with AHA has gained attention, with several case reports and clinical trials emerging [4,8,9]. Many of these reports describe a clinical dilemma between initiating high-dose immunosuppression immediately in combination with BPAs or opting for emicizumab to delay immunosuppression. Here, we highlight three cases of AHA in elderly patients, each with distinct clinical profiles requiring tailored therapeutic strategies. For instance, the first patient had a strict indication for anticoagulation due to her mechanical tricuspid valve and simultaneously required treatment with BPAs for a significant bleeding tendency. In this complex situation, our priority was the rapid eradication of the inhibitor. In contrast, the second case presented with no bleeding tendency, leading us to reason that emicizumab would have been a reasonable initial approach. In the third case, the very high inhibitor titre required immediate start of high dose immunosuppression and subsequent treatment of the bleeding with BPAs, with no place to consider emicizumab.

In our opinion, a key strategy for managing patients with AHA is to assess thrombotic risk and balance it against the need to control bleeding. This approach should consider the urgency of inhibitor eradication in cases of acute bleeding that require BPAs. Alternatively, for frail patients without active bleeding, postponing or reducing immunosuppressive therapy may be a viable option. However, these options need not be mutually exclusive. Therefore, we propose to conduct a randomised clinical trial involving both emicizumab and immunosuppressive therapies to determine the most suitable treatment for patients with AHA and different clinical characteristics.