Haemophilia A and B (HA/HB) are rare congenital, X-linked recessive bleeding disorders caused by deficiency of clotting factor VIII (FVIII) or IX (FIX), respectively. Disease severity is defined by reduced levels of FVIII or FIX [1,2]. Haemophilia is characterised by increased risk of spontaneous or traumatic bleeding in joints, muscles, or soft tissues [1]. People with HA/HB with inhibitors (HAwI/HBwI) have high risk of serious bleeding and joint/muscle damage, as well as higher treatment related costs and limited treatment options [3,4].

Current guidelines recommend life-long prophylaxis with clotting factor replacement therapy or non factor therapy to prevent bleeding episodes [5]. The evolution of prophylactic treatments, such as extended half-life factor replacement therapies (e.g., recombinant FVIII [rFVIII] and recombinant FIX [rFIX] administered intravenously) [6] and emicizumab (indicated for people with HA/HAwI) [7], a bispecific monoclonal antibody that mimics the activity of endogenous FVIII administered subcutaneously [8,9], has significantly improved life expectancy and quality of life (QoL) for people with haemophilia (PwH) [1]. Despite these advances, unmet needs in haemophilia remain. Intravenous injections may be associated with significant treatment burden due to pain, time required for preparation of injection, and possible venous access issues, particularly when frequent injections are required [10].

In France, all anti-haemophilic treatment costs are fully covered by national health insurance [11]. However, conventional treatment involves factor replacement therapies that are dispensed via hospital pharmacies (as opposed to community pharmacies), resulting in accessibility constraints for PwH and their caregivers, particularly for those on long term prophylaxis [12,13]. This leads to a significant burden, mainly associated with travel time and prolonged waiting times at hospital pharmacies. These issues may be exacerbated when the patient is underage, or when there are socioeconomic limitations regarding travel costs[8,12,13]. Although emicizumab is available at community pharmacies, reliance on hospital pharmacies continues to be a burden for PwH receiving factor replacement therapies in France [8].

To further understand remaining and emerging unmet needs and treatment burden in PwH, real-world data on the experience of living with haemophilia would be valuable. We therefore sought to investigate patient perspectives on the unmet needs associated with management of haemophilia, focusing on treatment burden, via ethnographic interviews with PwH in France.

METHODS

Recruitment and selection of PwH

PwH or their caregivers who showed interest in participating in the study were recruited through referrals from healthcare providers (HCPs), with the support of a specialised medical patient research agency in accordance with French and European Law [14]. The recruitment process was conducted without the involvement of patient associations in order to reduce the risk of bias, by ensuring that the recruitment of PwH was based on clinical criteria and medical suitability, and by limiting potential influence on the personal perspectives of PwH.

Characteristics considered during recruitment, conducted using a haemophilia research screening questionnaire, were aimed at capturing a diverse range of PwH: age (adults and children <18 years), sex (male and female), socioeconomic/educational background, residential area (urban, suburban, and rural), and treatment type. People with HAwI and HBwI/HB were eligible to participate in the study. People with HA were not the focus of this study given the wider range of available treatments for them. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient (or legal guardian) before any study related activities took place, and all patient data were anonymised prior to analysis.

Ethnographic interviews

Ethnography is a qualitative research method used to study a population of interest, examining their social and cultural environments through observation and interviews [15]. In healthcare, ethnography can provide researchers with a deeper understanding of patients and HCPs, as well as interactions between the two and the complex dynamics that influence healthcare delivery [16].

Ethnographic interviews were conducted face to face at the homes of PwH in February/March 2023. The interviews were semi-structured, each lasting approximately three hours, and included open-ended questions on living with haemophilia in France; e.g., identity and social perception, routines around managing the condition, history of treatments, changing needs, and hopes for the future (Table 1).

Interview analysis

All interviews were recorded and transcribed using Grain (Grain Intelligence Inc., 2018)[17]. Following each interview, analysis was conducted to identify words, sentence clusters, and statements that revealed common hopes and needs for PwH. For example, PwH consistently expressed a desire to lead a normal 48 life similar to people without haemophilia, leading the interviewer to identify normalcy as a core theme. Words, expressions, and sentences describing this need such as ‘be like others’, ‘live like others’, ‘be normal’, ‘not being judged’, ‘not standing out’, and ‘no stigma’ were collected. The library of words describing normalcy was refined and NVIVO 14 (version 14, QSR International, 2023) [18] was used to track their frequency across the PwH. This process was used to identify core themes.

Table 1.

Example questions from the ethnographic interviews

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Patient demographics

Emerging unmet needs in PwH were explored using ethnographic interviews in France to investigate patient perspectives, with a focus on treatment burden.

A total of 13 PwH were interviewed (HAwI: n=6; HB: n=7; male, n=12; female, n=1; median age, 44 years [IQR, 49–34]), of whom 11 were adults and two were children (8–10 years old; interviewed with their caregivers) (Table 2). The small sample size was influenced by challenges associated with finding PwH who were willing to be interviewed in person.

People with HB and HAwI were included in the study because their input was deemed of particular interest. There are no subcutaneous treatment options for HB, while people with HAwI already have experience with a subcutaneous treatment (emicizumab) and could provide potentially transferrable insights for people with HB/HBwI.

People with HBwI could not be recruited, likely due to the rarity of the disease.

Of the six people with HAwI, four were treated with emicizumab. The remaining two were treated with factor replacement therapies including conventional (standard half-life) FVIII and extended half-life clotting factors: one was undergoing immune tolerance induction and one developed inhibitors shortly before the interview. All seven people with HB were treated with extended half-life clotting factors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of interviewed patients with haemophilia in France (N=13)

| HAEMOPHILIA TYPE | SEX | TREATMENT AT TIME OF INTERVIEW | FREQUENCY |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| HAwI | Male | Emicizumab | Q2W |

| Male | Emicizumab | QW | |

| Male | Emicizumab | Q2W | |

| Male | Emicizumab | QW | |

| Male | EHL rFVIII (efmoroctocog alfa)* | TIW | |

| Male | FVIII (simoctocog alfa)* | QD | |

|

|

|||

| HB | Male | EHL rFIX (eftrenonacog alfa) | TIW |

| Male | EHL rFIX (eftrenonacog alfa) | QW | |

| Male | EHL rFIX (eftrenonacog alfa) | QW | |

| Male | EHL rFIX (eftrenonacog alfa) | QW | |

| Male | EHL rFIX (eftrenonacog alfa) | QW | |

| Male | EHL rFIX (eftrenonacog alfa) | QW | |

| Female | EHL rIX-FP (albutrepenonacog alfa) | Q2W | |

* Among the two people with HAwI who were treated with factor replacement therapies in this study, one had HA without inhibitors before this study began and was advised by a haematologist to switch to emicizumab. This person remained on EHL rFVIII (efmoroctocog alfa) due to a lack of understanding of the transition process between treatments and the impact it would have on daily life. Inhibitors to FVIII developed in this person during the interview period. The other person with HAwI in this study was treated with FVIII (simoctocog alfa) and underwent immune tolerance induction to eradicate FVIII inhibitors.

Emerging themes from ethnographic interviews

Three core themes around treatment emerged from discussions with PwH during the interviews:

Efficiency (i.e., perceived protection from bleeding episodes)

Autonomy (i.e., independence regarding treatment administration and lifestyle)

Normalcy (social awareness and acceptance of haemophilia treatment).

These were identified as core themes because they were mentioned throughout all interviews, either as desires for future treatments or as benefits gained through new treatments such as emicizumab, and spanned different age groups and haemophilia types.

Other identified themes include community (i.e., the need to connect with other PwH) and education (i.e., the need to learn more about the condition). However, these needs were only expressed by some PwH in this study. Education emerged as particularly significant for younger PwH and those more interested in understanding their condition, in contrast to those who simply sought effective treatment with less time or interest for extensive information.

Themes that were excluded from this study include seeking community or shared identity shaped by stigma and trauma. These themes are already well documented and primarily relevant to older PwH rather than younger ones.

The results are presented and discussed under the three core themes.

Efficiency

Based on data collected during the ethnographic interviews, efficiency was defined as the perception that the treatment provides an optimal protection over an extended period of time. People with HB judged treatment efficiency by perceived clotting factor levels. Their perception of declining clotting factor levels over time created anxiety and limited their capabilities (Table 3, Efficiency: A).

People with HAwI who switched from intravenous factor treatment to emicizumab viewed efficiency as a ‘plateau’, meaning that they perceived their bleed protection as both constant and durable. PwH gradually established trust in the treatment over time (Table 3, Efficiency: B). Although subcutaneous emicizumab imitates the haemostatic action of intravenous FVIII, it has a more constant level of haemostatic activity that differs from the peaks and troughs observed with FVIII [9]. Moreover, unlike FVIII, emicizumab can be administered at infrequent intervals and has a lower risk of immunogenicity vs factor replacement [7,9].

Table 3.

Patient perspectives on the management of haemophilia in France

The table shows select patient quotes that were highlighted following data analysis.

An ethnographic multinational study, in which data were collected through 8–12 hours of PwH observation, written exercises, semi structured interviews, and facilitated group dialogues, revealed that 52% of PwH had challenges with translating clinical understanding of treatment efficacy into daily life activities. Their mental models of protection reinforced either overly cautious or risky behaviour [19]. In the same study [20], following a switch from conventional to extended half life treatment, some caregivers were overly cautious and would not allow their children to enjoy the potential benefits of longer protection, as they considered protection to be insufficient on non treatment days. This level of treatment uncertainty shows a need to develop communication tools and materials to improve education of PwH on protection received from their new treatment regimen, especially if it involves a different mechanism of action.

Autonomy

Participants expressed individual priorities with regards to autonomy and what it means to them. One key aspect of autonomy for some PwH was the ability to understand and administer treatment in a convenient and practical way, independently from others. Haemophilia management strategies are evolving from a culture of only measuring treatment success based on annual bleeding rate to a more holistic view inclusive of QoL and focusing on autonomy. In the current study, PwH appreciated the increased autonomy of being on prophylactic treatment, as it provided them with more confidence in conducting day to day activities (e.g., travelling) (Table 3, Autonomy: A).

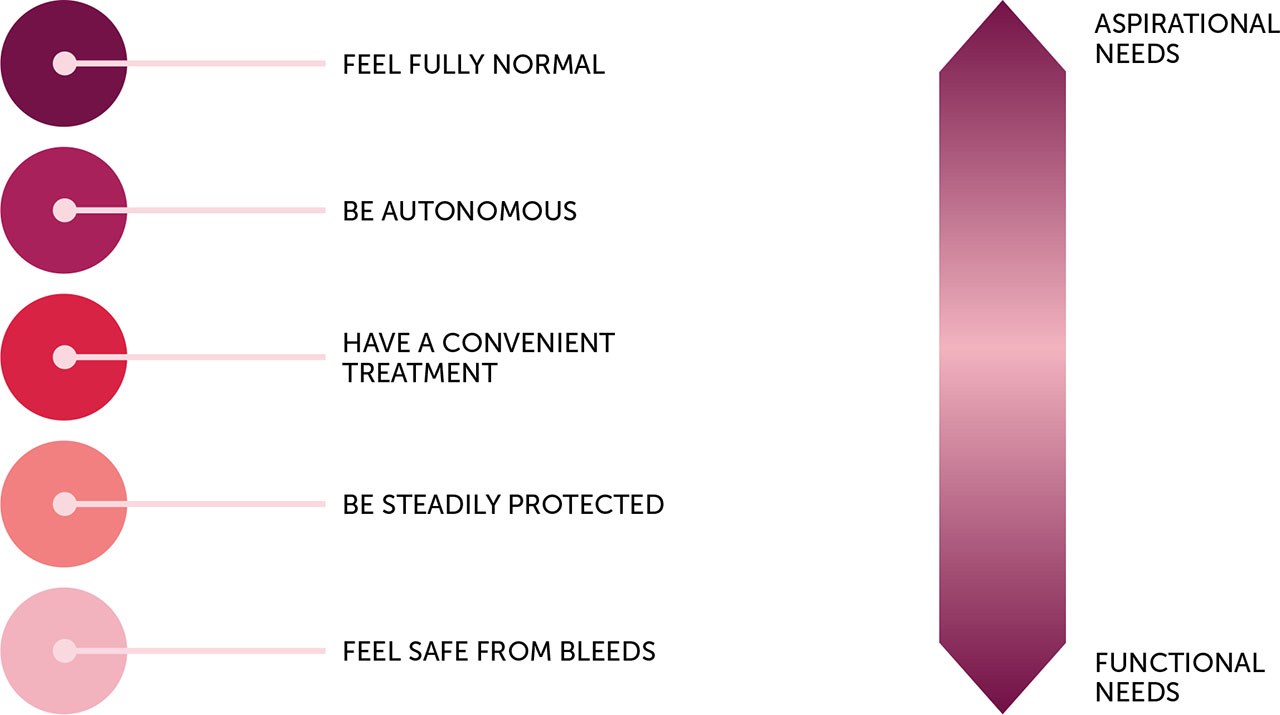

Figure 1.

Patient perspectives on functional and aspirational haemophilia treatment needs in France

Results from ethnographic interviews on patient perspectives of haemophilia treatment goals in France (N=13), ranked according to the type of need (functional vs aspirational).

Another important aspect of autonomy was having readily accessible treatment, as that allows PwH to be less dependent on healthcare system structures (Table 3, Autonomy: B-C). Evidence of increased access to emicizumab for PwH upon distribution in community pharmacies (in addition to hospital pharmacies) was reported in a recent study in France [8]. The same study also showed that PwH were satisfied with the reduced travel time as well as relationships formed with local pharmacists.

Some PwH in the current study highlighted treatment storage and portability as important aspects of autonomy. For example, treatments kept at room temperature allow increased storage and travel flexibility. A 2018 qualitative study conducted across seven countries (Argentina, Brazil, France, Italy, Japan, Mexico, and the UK) reported that >40% of people with HA receiving prophylactic rFVIII were dissatisfied with their treatment due to storage challenges [21]. The study further demonstrated that the satisfaction of PwH with the treatment increased if it did not require refrigeration as this imposed fewer restrictions on daily activities [21].

Although PwH who consider independence from the healthcare system as an important aspect of autonomy may not regard haemophilia centres as a key component of their treatment journey, these are highly valued by others, including caregivers of children with haemophilia who may greatly benefit from the knowledge and care provided by specialists and other staff members in these centres (Table 3, Autonomy: D). Caregivers of children with haemophilia face many practical and emotional/psychological challenges, including coordination of treatment schedules, ensuring adequate treatment supply, and dealing with complications associated with administering intravenous treatment (e.g., repeated venipuncture and fear of needles), as highlighted in several studies of caregivers[22,23,24,25]. Nurses play a particularly important role in supporting PwH and their caregivers as they are usually the first point of contact [26]. Many nurses have extended their roles to include direct care (e.g., preparing and administering treatment for PwH), education (acting as a reliable source of information about existing and new treatments), forming a bridge between PwH and haematologists, and becoming a trusted contact for children [26,27].

Normalcy

When discussing normalcy, PwH in the current study defined it as the ability to administer treatment in a way that does not evoke judgement by others and does not stigmatise them. Normalcy was highly valued by PwH, including those who were broadly satisfied with their current treatment. The concept of ‘everyday peace of mind’, meaning protection on a physical and emotional level, was ranked as most important, corresponding with the aspirational need to ‘feel fully normal’. Figure 1 represents a summary of key aspects highlighted by the PwH in this study based on their functional and aspirational treatment needs. Fundamentally, PwH strongly desire to live a normal life, free of their haemophilia, as captured in the concept of a ‘haemophilia free mind’, which encompasses freedom from bleeding, arthropathy, pain, and treatment burden [28]. In this study, PwH on emicizumab or factor treatments struggled with the mental and social burden of treatment. They felt uncomfortable to treat themselves in public because of social stigma, and usually had a dedicated private place for treatment administration. Social stigma remains a significant barrier to normalcy, even with the emergence of new therapies (Table 3, Normalcy: A-B).

A recent ethnographic study found that 48% of families of PwH described life with haemophilia as normal [29]. Many HCPs shared the same sentiment, despite the apparent treatment related burden and limitations that persisted in the daily lives of PwH, as observed in the same study population [20,29]. Caution needs to be exercised when defining normalcy in PwH, which has been loosely characterized as a life relatively unburdened by the disease [29]. The definition of normalcy may also vary across generations. Older generations are shaped by the memory of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis infections [30], but their significance for younger generations is decreasing [29]. In addition, the perspective of older PwH is influenced by the recent past of a poor QoL (e.g., inferior treatment options and profoundly restricted lifestyles) and has reinforced the notion of a current normal life with haemophilia [20,29]. Recent studies, including ethnographic interviews, have observed a stronger desire for normalcy in the younger generation (children and teenagers), due to feeling marginalised during daily activities[20,29,31]. PwH and their caregivers have cited psychosocial issues as one of the factors that negatively impacted patient QoL[20,22,32].

In light of the variety of contributors to perception of normalcy by PwH, personalised and optimised treatment approaches that consider the physical and psychological burdens and needs of PwH and their caregivers should be the ultimate goal in haemophilia care [28,33,34,35].

Limitations of ethnographic interviews

Despite the advantages of ethnographic interviews, there are some limitations associated with this methodology. In general, ethnography requires a laborious and detailed data collection process, making it time- and resource-intensive, which often limits the sample size [36]. In addition, the lack of a clear and precise scientific question inhibits the determination of an actual sample size in ethnographic interviews. The sample size in the current interviews was influenced by challenges associated with recruitment of PwH and may preclude generalisability of findings [36].

The need for a researcher to engage participants in person creates additional challenges in ethnographic interviews. These include potential researcher bias occurring due to the ethnographer’s possible influence on the behaviours and responses of PwH [36]. The researcher’s ability to gather accurate information also depends on them being accepted within the surveyed community/culture [36].

CONCLUSION

French PwH in our study evaluated their treatment primarily based on perceived efficiency, autonomy, and normalcy, with normalcy being highly valued by the study participants. Perception of treatment efficiency was based on their understanding of the mechanism of action of a treatment. The meaning of autonomy varied between PwH, with some prioritising independence from the healthcare system, and others viewing treatment accessibility and storage as most impactful on their day-to-day activities. The need to feel normal, without having to endure the social stigma that can be associated with treatment administration, was highlighted as key by PwH. Collectively, these findings reinforce the goal of targeted and personalised treatment approaches in haemophilia care, with emphasis on addressing both functional and aspirational treatment needs of PwH.