Haemophilia A is a congenital bleeding disorder caused by factor VIII (FVIII) deficiency [1]. Disease severity depends on the level of FVIII in blood and ranges from mild (>5% to <40%), to moderate (1% to 5%), and severe (<1%) [2]. Severe haemophilia A is associated with serious spontaneous bleeding in muscles, soft tissues, and joints [3].

Haemarthrosis, or bleeding into joints, is one of the clinical hallmarks of haemophilia A and occurs most commonly in knees, elbows, and ankles [4]. Early manifestations of acute haemarthrosis are mild discomfort and slight limitation of joint motion, followed by pain, joint swelling and cutaneous warmth [5].

Haemophilic arthropathy is a serious complication of haemophilia-induced joint bleeding [6]. It is characterised by synovitis of the joint, which in turn increases the tendency of frequently recurring haemarthroses in the same joint. This is followed by narrowing of the joint space due to loss of the cartilage, development of bone cysts, chronic pain, and limitation of motion, leading to permanent disability [5].

The standard of care for haemophilia A is the intravenous administration of FVIII concentrate to treat or prevent bleeding [7]. However, treatments are now being developed to overcome the disadvantages associated with FVIII concentrates, particularly frequent intravenous administration and development of inhibitors (anti-FVIII antibodies) [8]. Emicizumab is a novel non-factor replacement therapeutic agent with proven efficacy for preventing or reducing the frequency of bleeding episodes in adults and children with haemophilia A with or without inhibitors [9]. It is a bispecific monoclonal antibody designed to mimic the activity of activated FVIII [8].

In clinical studies, subcutaneous emicizumab prophylaxis has shown clinically significant prevention or reduction of bleeding episodes in children aged <12 years with haemophilia A with or without inhibitors [10,11]. It has also shown considerable improvement in health-related quality of life (QoL) [12]. We report a case of a child with severe haemophilia A without inhibitors, complicated by haemarthrosis, and successfully treated with emicizumab.

CASE PRESENTATION

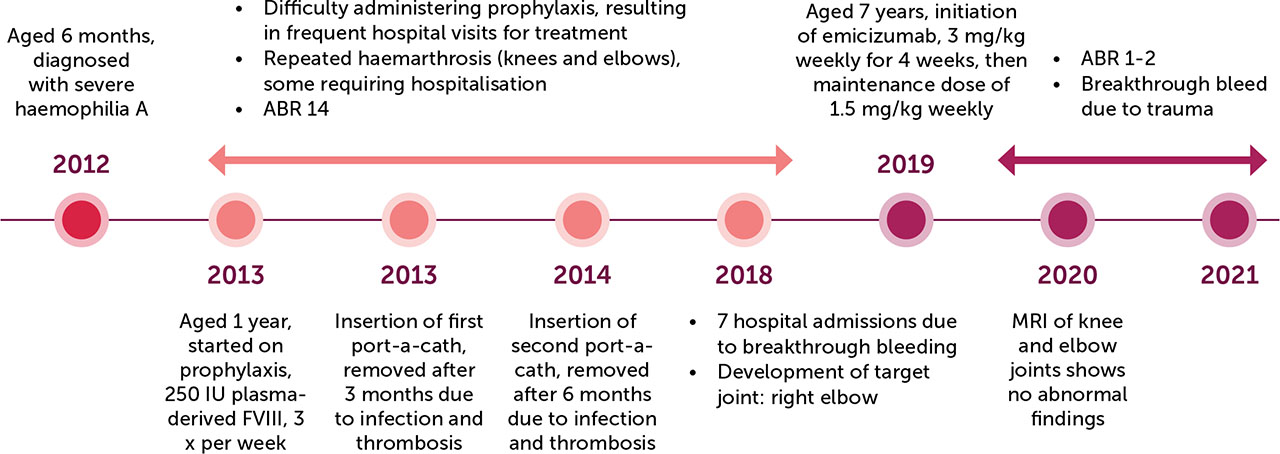

Q is an Omani boy, now 10 years old, with a history of severe haemophilia A and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. He was diagnosed at the age of 6 months when he presented with spontaneous bruising with a FVIII level of < 1%. Since then, he has been on regular follow-up in the Department of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology at the Royal Hospital, Muscat. He has a strong family history of haemophilia, with one maternal uncle and six maternal cousins affected. His parents are first cousins; his three other sisters have no significant medical issues.

Since being diagnosed, Q had frequent emergency department (ED) visits with haematomas and was managed with on-demand plasma-derived FVIII. At the age of one year, he was started on prophylactic treatment with 250 IU (40 IU/kg) plasma-derived FVIII three times per week after inserting a port-a-cath. As per our local protocol, the prophylactic dose of FVIII is 25–40 IU/kg and the on-demand therapy dose is 50 IU/kg. Recombinant FVIII was not available due to supply issues.

Q’s subsequent clinical course was complicated by multiple breakthrough bleeding episodes, including haemarthrosis (knee and elbow), some of which required hospital admission. The frequency of breakthrough bleeding episodes continued to increase. In addition to repeated visits to the emergency department, he had seven hospital admissions in 2018 (he was 6 years old). Although some episodes were caused by minor trauma, most were spontaneous. He also developed a right elbow target joint. Based on physical examination, joint health has been grossly normal. Normal contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of bilateral knee joints was undertaken with no abnormality identified.

Doses of prophylactic FVIII were adjusted as per our local protocol. His FVIII inhibitor screening has always been negative. Serologies for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus were also negative.

The worsening of the child’s clinical course was attributed to multiple factors. He is overweight (body mass index (BMI) 19.8 kg/m2; 88th percentile) with difficult intravenous access. Furthermore, he had two port-a-cath insertions in different locations (first port-a-cath inserted for 3 months and the second for 6 months) but both had to be removed due to infection and thrombosis. Moreover, he could not be started on home treatment due to his mother’s hesitation. This resulted in difficulties in prophylactic treatment administration. He also had difficult socioeconomic circumstances. His mother left her job after his condition worsened. The child was transferred to a school near the treating centre to accommodate frequent hospital visits, as he had to attend regularly to receive prophylactic and on-demand treatment. His mother was offered psychological support.

Taking the aforementioned challenges into consideration, treating physicians decided to start Q on emicizumab. It took some time for the hospital administration to agree on this therapy since he did not have inhibitors, which was the only indication approved by them to start the drug. Emicizumab was started on 13 March 2019 (when he was 7 years old) with an initial weekly dose of 3 mg/kg injected subcutaneously for 4 weeks, followed by a maintenance dose of 1.5 mg/Kg weekly as per protocol.

The introduction of emicizumab has resulted in substantial clinical improvement. Q had no breakthrough bleeding for almost two years after starting emicizumab, except for one episode of trauma-induced haemarthrosis. His annual bleeding rate (ABR) improved from 14 to around 1–2, and he did not experience any significant joint pain or swelling. He has returned to regular school and has shown improvement in academic grades. His mother returned to work, which has also resulted in socio-economic improvement. Latest investigations revealed normal blood counts and blood chemistry (renal function, liver function), and bone profile. Complete blood count (including white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets) is done at our centre for patients with haemophilia treated with emicizumab to monitor for the risk of thrombotic microangiopathy, to detect early thrombocytopenia or anaemia. For our patient, complete blood count has always been within normal ranges.

After one year of starting emicizumab, our patient complained of multiple joint pain with no swelling. MRI of knee and elbow joints was done and showed no abnormal findings. He has continued to receive a weekly dose of 1.5 mg/kg emicizumab administered subcutaneously at home and is followed up in clinic every 3 months.

A timeline of the case is shown in Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

Haemarthrosis is a major complication of haemophilia A [13]. Appropriate management of joint disease in people with haemophilia A includes early prevention and treatment of acute joint bleeds before the onset of degenerative arthropathy [3,14]. Starting prophylaxis with factor concentrates at an early age helps to prevent and reduce the risk of joint bleeding and arthropathy [15,16,17]. The child in our case study started receiving prophylactic doses of FVIII at an early age after being diagnosed with haemophilia A. This timely management may explain the normal findings of the latest MRI of his joints. Poor management of recurrent haemarthrosis can result in abnormal bone growth and limb length, chronic synovitis, degenerative arthritis [14,18], chronic pain [13], reduced range of movement of joints [19], and impaired QoL [13].

Emicizumab was initiated for the child after being poorly compliant to FVIII prophylactic treatment. Emicizumab is the first non-factor therapy approved for prophylaxis in haemophilia A [20]. Its subcutaneous route of administration represents a convenient choice for self-administration away from central venous access devices and hospital admission; thus supporting improved compliance to treatment. Ultimately, this can help promote an active lifestyle and improve health-related QoL [21]. In addition, several clinical trials have demonstrated that emicizumab is effective and safe for the prevention of bleeding in children and adults with haemophilia A irrespective of FVIII inhibitors. Emicizumab prophylaxis showed substantial reduction in ABRs of treated bleeds, and most participants receiving emicizumab (54% to 90%) did not report any treated bleeds [10,22,23,24]. Similarly, long-term emicizumab prophylaxis was associated with low ABRs and reduced bleeding into joints with no new events [25].

In the HAVEN 2 clinical trial, which included children <12 years with haemophilia A with inhibitors, 100% of all evaluable target joints resolved during the study period [10]. The World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) guidelines recommend using emicizumab prophylaxis to prevent haemarthrosis, and both spontaneous and breakthrough bleeding in persons with severe haemophilia A without inhibitors [26]. Our child did not experience joint bleeding, pain, or swelling after the initiation of emicizumab. This improvement in his clinical status may be reflected as an improvement in the patient’s QoL and support maintenance of joint health into adulthood [10]. However, standard QoL assessment was not available.

Intravenous administration of FVIII concentrate, frequent hospital visits, and haemarthrosis were factors that impaired the child’s QoL. However, his clinical and socio-economic status were improved after the initiation of emicizumab administered subcutaneously, once weekly, and at home. In particular, substantial physical health and clinical improvement were characterised by no breakthrough bleeding for almost the first two years, improvement in ABR improved, and no significant joint pain or swelling. In terms of daily activities, he has returned to regular school and has shown improvement in academic grades. The HAVEN 2 clinical trial assessed the impact of emicizumab prophylaxis on health-related QoL in children with haemophilia A and their caregivers. Results showed that emicizumab was associated with substantial and sustained improvements in health-related QoL in both children with haemophilia A and their caregivers [12]. Children’s health-related QoL improved in terms of physical health, reduced absence from school, and fewer hospitalisations; caregivers observed similar improvements in their children’s health-related QoL [12]. The HAVEN2 trial also demonstrated that emicizumab reduced caregiver burden and increased their satisfaction with treatment. This was further emphasised by improvements reported in the ‘Family Life’ domain of QoL [12]. In a similar context, our patient’s mother returned back to work, which was accompanied by socio-economic improvement.

CONCLUSION

Emicizumab was introduced as a novel non-factor therapy for haemophilia A, representing an effective and convenient alternative to conventional FVIII concentrate. The subcutaneous route of administration, without the need for hospital admission, made emicizumab a suitable option for self- or home-administration, thus, treatment compliance was improved in the case reported here. Consequently, disease-related complications, particularly haemarthrosis, were resolved and the QoL of the child and his caregiver was improved after the initiation of emicizumab.