EHC Think Tank members used the concept of a ‘guiding star’ and associated ‘near stars’ to identify steps to address challenges in the health care system around access equity and future care pathways for rare diseases

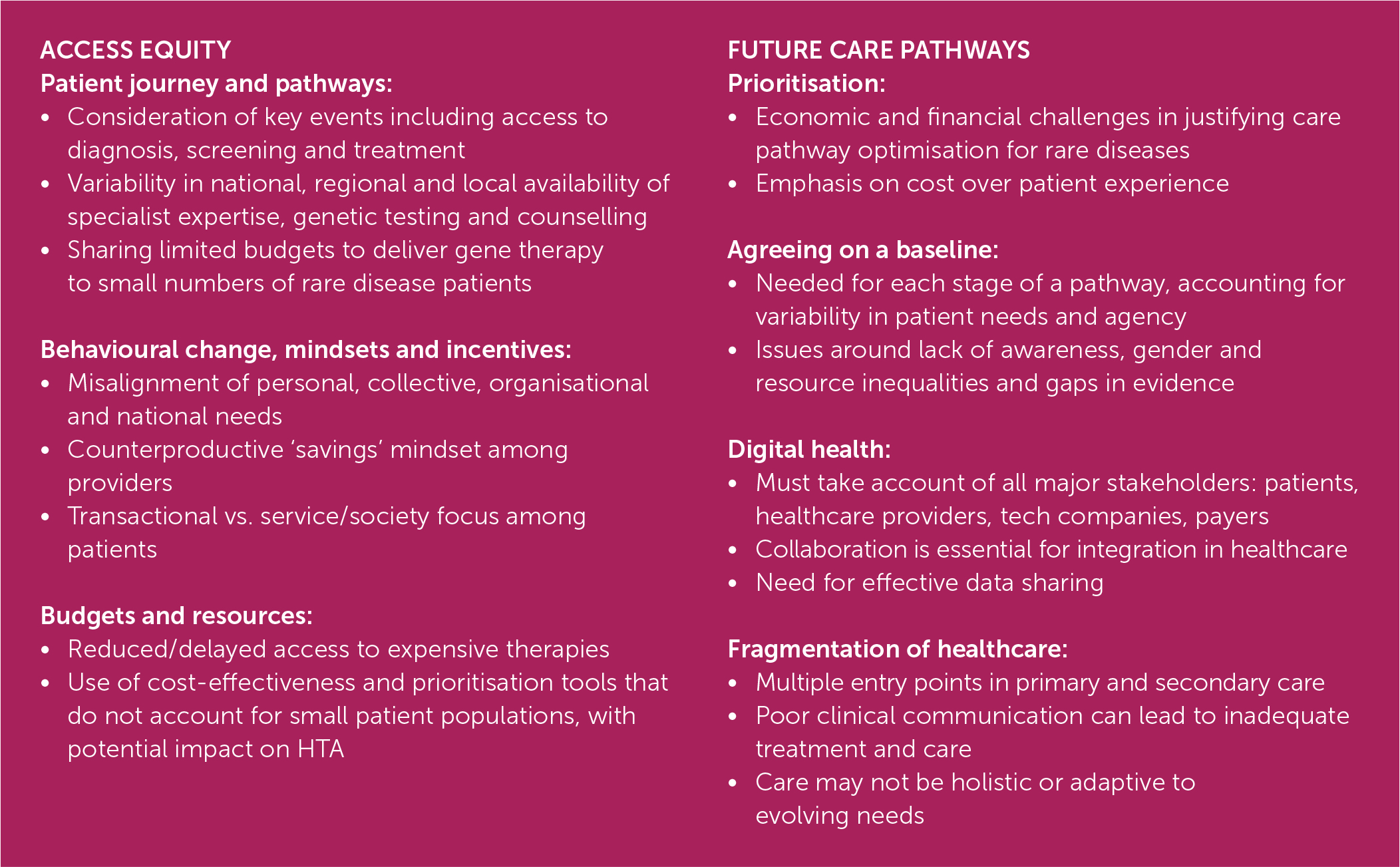

At the first workshops of the EHC Think Tank Workstreams on Access Equity and Future Care Pathways, respectively, stakeholders representing healthcare providers, patient groups, regulators, policymakers, research and industry, participated in virtual meetings to identify challenges to progress in these important areas related to patient care (Figure 1), and to propose potential solutions [1,2]. Following the format of other Think Tank Workstreams, the second workshops for each of the workstreams involved participants working towards consensus on:

Identifying a ‘guiding star’ to determine the direction/course for ongoing focus

Defining achievable ‘near star’ milestones

Exploring the enablers and constraints to achieving these milestones.

Figure 1.

Summary of challenges to progress to equitable access to care (Access Equity) and enabling improved care pathways (Future Care Pathways) [1,2]

GUIDING STARS

The symbol of a ‘guiding star’ was used to align each workstream around a long-term, ambitious, but realistically achievable solution derived from the challenges identified in the first workshops.

Access Equity

The guiding star for Access Equity is aimed at addressing challenges around the patient journey and pathways, behavioural change, mindsets and incentives, budget and resources, creating transparency, upcoming supply issues for therapies, uncertainty regarding regulations, and information and education, including health literacy [1]. As such, the group proposed that it should aspire to a healthcare system that gives the patient the ability to benefit from care and treatment fairly and impartially (Figure 2).

Future Care Pathways

The Future Care Pathways Workstream formulated a guiding star to address challenges regarding financial challenges, the need to agree on a baseline for specific pathways and keep them updated and relevant, digital health, and fragmentation of healthcare [2]. The guiding star proposed, was the right intervention at the right time by the right healthcare professional in the right formats with a variety of methods of delivery to suit the person, (Figure 3).

NEAR STARS

The symbol of ‘near stars’ was used to chart several shorter-term, more readily achievable milestones along the path towards the long-term guiding star goal for each workstream (Figures 2 and 3). All near-star goals are subject to adjustment based on work progressing, and the system reacting in response. As a dynamic process, this may lead to new learnings that reorient towards other or new near-star goals ultimately progressing towards the guiding star. Both workstreams identified goals related to behavioural change.

Near-star goals for the Workstream on Access Equity were:

Changing the narrative on budget and resources

Changing the behaviours of stakeholders in the healthcare system.

Those identified by the Workstream on Future Care Pathways were:

Creating combined digital and human pathways

Using patient behaviour to inform nudges and incentives

Creating data-driven pathways.

CHANGING THE NARRATIVE ON BUDGET AND RESOURCES

1.

Participants in the Workstream on Access Equity felt that changing the narrative from a ‘cost’ to an ‘investment’ perspective could enable a healthier society in the future. This requires a redefinition of the perception of ‘value’, whereby the system moves beyond healthcare decisions based largely on monetary considerations towards an approach that considers value in terms that include broader societal benefits and long-term gains [3,4]. Greater transparency is needed in decision-making, particularly in Health Technology Assessment, pricing and negotiations, and the regulation of access to treatment, healthcare and social services [5]. Even with the framework established by the new European Regulation on Health Technology, which is due to come into effect in 2025 [6], it is yet to be seen how challenges around input from patient groups and the use of real-world evidence will bring in broader perspectives, and HTA processes will continue to differ between countries as a result of differences in healthcare systems and payers. Improving partnerships between healthcare system stakeholders, including patients, would help to foster trust, growth, and collaboration [7], including partnerships between seemingly more disparate entities, such as researchers and commercial enterprises. Amplifying, sharing and mainstreaming best practice public-civic-private partnerships could be a helpful first step.

The healthcare narrative needs to move from a focus on funding for ‘fixing the patient’ to proactive investment in early intervention and prevention of comorbidities, with the potential to improve overall health and reduce long-term healthcare costs [8,9]. A more holistic perspective takes account of the ability to return to work and care for family – not just the price of treatment [10,11]. The merits of investing in ‘living better for a longer time’ rather than ‘waiting for serious illness’ need to be better understood. This links to broader discussions about equity and fostering a transition from an ‘us vs. them’ approach to a focus on specific relevant health outcomes and values aligned with patient needs [12]. Measuring outcomes will be essential for achieving effective healthcare budget allocation, including capturing non-monetary benefits to assess genuine return on healthcare investment. However, if we wish to move towards a more societal perspective, defining, following and measuring these outcomes becomes more difficult.

At a governmental level, allocating a fixed share of gross domestic product (GDP) to healthcare may constrain change by limiting investment. Given that healthcare in Europe is generally funded by taxpayers who want to understand how their money is spent, a shift in the narrative should emphasise the importance of equitable distribution across age groups and patient populations [13]. Addressing short-term thinking, which often constrains long-term healthcare investment [14], is a priority, necessitating a shift towards longterm planning and budget allocation. Insights from behavioural science and change management can help reshape perceptions, align incentives, and promote behaviours that benefit individuals and society [15].

Considerable constraints remain, not least the complex interplay of diverse national healthcare systems across Europe and the lack of a universally agreed way to identify and measure value and its implications for long-term planning and investment. Innovative pilots and data projects play a crucial role in driving change in healthcare [16]. The COVID-19 pandemic has also underscored the importance of health and equitable access to healthcare services [17]. Overall, these shifts in narrative can pave the way towards a more equitable and effective healthcare system that acknowledges patients as people, living healthy lives, supported by insights from secure and optionally open-source long-term data.

CHANGE OF BEHAVIOUR

2.

The need for behavioural change underpinned achievable shorter-term goals for both the Access Equity and Future Care Pathways Workstreams.

To move towards a healthcare system that enables the patient to benefit from care and treatment fairly and impartially, participants in the second Access Equity workshop recommended investigating healthcare stakeholders' mindsets and intrinsic incentives in the healthcare system [18,19] that may facilitate a change in stakeholder behaviour.

Transformation towards more equitable access to healthcare could potentially be powered by evidencebased narratives, as demonstrated by initiatives such as the European Reference Networks (ERNs) for rare diseases [20,21]. These virtual, pan-European healthcare provider networks aim to facilitate discussion on complex or rare diseases and conditions that require highly specialised treatment and concentrate knowledge and resources [19]. At a national level, the concept of Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) is gaining momentum and facilitating changes that support the types of stakeholder collaboration required in healthcare [22]. The strong and committed multi-stakeholder collaboration and broader communication found in initiatives of this kind should be supported and facilitated as enablers for behavioural change.

Multi-level stakeholder collaboration will be paramount to reinforce the urgency of the need for action to ensure a healthy healthcare system. In addition, visionary leadership, training, and capacity building will empower healthcare professionals (HCPs) to provide inclusive care. Leveraging research in change management and behavioural science can equip healthcare systems with strategies to influence behaviour positively [16].

Regarding stakeholder behaviour, the main constraints on progress towards Access Equity are a lack of accountability and a tendency to assume issues are other stakeholders’ responsibility [23]. Resistance to change is a natural human characteristic, and attitudes are entrenched in healthcare systems, with the potential for power struggles among stakeholders and clashes of personality [24]. The scale of change needed may present a constraint, and even identifying a starting point may be difficult. Conducting a behaviour change pilot could be useful, especially in starting and testing a change intervention. However, this would not guarantee that lasting, positive changes would be scalable across organisations and projects – examples of pilots being translated to (inter)national programs are scarce. Lack of persistence may also constrain progress; a commitment and belief in long-term change will be needed, alongside accepting that progress may occur in small steps and victories may be limited – at least early on.

Incentives were also considered important for the successful development of Future Care Pathways, notably at critical points of the patient pathway to achieve optimal outcomes, such as the time of diagnosis. Understanding a patient’s behaviour before and while on a pathway will help determine the need for and format of nudges and incentives, e.g., psychological or financial.

Participants in the Workstream on Future Care Pathways identified a series of enablers for implementing the behaviours, nudges to patients and incentives for innovation that are needed at different stages and times while taking account of changes to patients’ lives. A multidisciplinary network, including the community, organisations and volunteers, could facilitate seamless, joined-up provision of care by signposting and supporting patients along care pathways. Nudges could be included at key points in pathways to remind patients of necessary actions [25,26].

An early prevention mindset should be encouraged across healthcare systems so that, for example, prophylaxis is incorporated as a routine part of care pathways for bleeding disorders [27]. In addition, incentives are needed to nurture a culture of innovation in pathway development, with collaborative research and motivational payment models for care providers.

Changing behaviour is a multi-layered endeavour and this creates considerable challenges. Lack of time, effort and energy are likely to deter some stakeholders from contributing to the coordinated improvements needed to ensure care pathways where the right intervention at the right time by the right healthcare professional in the right formats with methods of delivery suited to the person is standard [28]. Resource constraints may impact the availability of financial incentives, thereby hindering networks of facilitators from fully performing their roles in guiding patients along their pathways. As with Access Equity, unclear accountability is also a constraint. Who is responsible for initiating change, and who will be affected by decisions? A lack of understanding of the objectives and reasons for behavioural change may leave stakeholders unsure of who is accountable and unwilling to take responsibility.

COMBINED DIGITAL AND HUMAN PATHWAYS

3.

Future Care Pathways need to be seamless and personalised, with integrated digital and AI-based technologies when applicable and relevant for patients, clinicians and healthcare systems, without losing the necessary human connection. This can enable real-time monitoring of pathway effectiveness. Key objectives and minimum standards must be agreed upon to achieve improved patient outcomes at affordable costs. Reference pathways should be defined that can be adapted to individual patient needs, and a coordinated and collaborative approach should be implemented between providers of clinical and social care, with input from providers of dental, housing, economic and educational support as needed [29,30]. Integrated and personalised health budgets for providers would facilitate this.

Human aspects, particularly trust between stakeholders and the system, are important enablers of change. Once this is established, other elements, such as shared decision-making between patients and HCPs, will follow. An organisational set-up should be defined which enables personalised pathways grounded in patient agency and evidence at all levels. Sharing common goals may make the organisation and implementation of pathways easier and potentially more cost-effective. Of the technical and digital aspects needed for the development of Future Care Pathways, the infrastructure of supercomputing and cloud solutions already exists, and is ready to be capitalised [17].

Despite this seemingly rosy outlook for combining digital and human aspects of Future Care Pathways, there are constraints. Financial and legal aspects need to be worked out before change is possible, and significant investment will be needed to develop and implement new processes and tools. Technical and digital challenges include inadequate implementation of technological infrastructure and limited systems integration [31,32] and the need for appropriate, unbiased data collection [33,34]. On the ‘human’ side, there is a risk that healthcare providers will feel pressured into implementing new care pathways before they are ready, making them hesitate to introduce new concepts, tools, and processes [32,33]. While recognising the value of collaboration, people and institutions may also be wary of working together and trusting each other [32]. There may be an element of power dynamics that delays or impedes progress in pathway development and implementation. Successful implementation will require human-centred design and the inclusion of patients at all stages for the technology to be ‘sticky’ and deliver sustainable mutual value [35].

OPTIMISING USE OF DATA

4.

Routine data collection from patients should be used to understand and improve each pathway for individual patients and for the collective patient group [36]. Key patient outcomes need to be defined, including patient-reported experience measures/patient-reported outcome measures (PREMs/PROMs), and the end goal for each pathway stage regarding long-term health. National initiatives using patient experience data to map and improve care pathways, including developing consensus-based care pathways, have been reported in areas including breast cancer and elective surgery [37,38], and could provide useful models for rare disease. Fragmented and inconsistent data collection and outcome measures across policy domains (e.g., healthcare, education, labour market, social security) create barriers to information sharing and outcome measurement that may delay progress in developing Access Equity and Future Care Pathways. However, initiatives are underway to harmonise data flow within and between European countries.

Launched by the European Commission in May 2022, the European Health Data Space (EHDS) has the potential to provide valuable information to inform evidence-based decision-making [39]. EHDS supports data sharing for better healthcare delivery, better research, innovation, and policymaking across Europe while maintaining full compliance with EU data protection standards. Approved organisations can access electronic data (e.g., patient summaries, e-prescriptions, images and image reports, laboratory results and discharge reports) in a common European format.

Established and planned use of electronic medical records and online registries enable easier patient data collection, and online platforms will facilitate the completion of PREM and PROM data [40]. There needs to be a clear purpose for collecting data, and HCPs and patients should be involved in decisions about what and how data are collected, how data are processed, and who has access to the data [41]. How data are handled and presented should make sense to both patients and HCPs, and patients wish to see that collected data are being actively used in treatment decisions. Established patient networks and advocates can help ensure patients’ visions and needs are acted upon.

The co-creation of data research studies between patients, academia, and life science companies can go a long way to addressing the needs of multiple stakeholders. Patient groups require support and knowledge to drive evidence-based data collection that can address their communities' unmet needs. The data collected from patients needs to serve more than one partner.

Several constraints are likely to impede the optimisation of data collection. Data collection and data entry are time-consuming for HCPs, and patients may resist completing questionnaires if they do not understand their value. Anyone involved in data collection must be aware of potential security issues and data protection requirements, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [42]. There is also a risk that inadequate data quality, data access, data interoperability, and representativeness of data may foster health inequalities [13,43].

SUMMARY AND NEXT STEPS

The EHC Think Tank’s Workstream on Access Equity aspires to a healthcare system that enables the patient to benefit from care and treatment fairly and impartially. Through an alternative co-creation process, workstream members identified focus areas, relating to behaviour, mindsets and narratives, which need to change to realise patient access equity.

The Workstream on Future Care Pathways argues that it is prudent to ensure the right intervention at the right time by the right healthcare professional in the right formats with a variety of methods of delivery to suit the person. Achieving this requires a focus on patient behaviour to inform nudges and incentives, embracing and utilising digital tools, and making decisions based on data-driven evidence.

The next step for each workstreams will be to explore the key enablers and constraints to progress towards these goals in more depth, and to develop a series of actions through which it is feasible for workstream members to facilitate positive change in the broader healthcare system.