The development of clearly defined, evidence-based future care pathways in rare disease faces multiple challenges related to prioritisation, minimum levels of care and fragmentation of services, with digital health presenting both opportunities and drawbacks

The care pathway is defined as “a complex intervention for the mutual decision-making and organisation of care processes for a well-defined group of patients during a well-defined period”, and its role is to enhance quality of care by improving patient outcomes, promoting patient safety, increasing patient satisfaction, and optimising the use of resources [1,2]. Implementing a care pathway has been shown to encourage clearer documentation and regular review of treatment [3], better guideline adherence [4], greater teamwork and organisation of care processes [5], and more efficient and standardised care delivery [6,7]. In rare diseases, accessing appropriate coordinated services is essential to ensuring timely diagnosis and proper treatment and care. However, the complex and multidisciplinary nature of many rare disease care pathways can result in similarly complex obstacles and barriers for all stakeholders, compounded by a lack of coordination [8,9]. The introduction of innovative therapies is adding to this complexity [10] and must also be addressed in the development of future care pathways.

The European Haemophilia Consortium’s (EHC) Think Tank Workstream on Future Care Pathways seeks to identify and address key challenges in shaping future care pathways that meet the needs of people with rare diseases while remaining practicable and affordable to healthcare providers in countries with different budgets and resources.

Participants at the first virtual workshop of the Future Care Pathways Workstream, on 14 February 2023, represented a range of stakeholders, including healthcare providers, patient groups, researchers, and industry. They reported multiple challenges, including fragmentation of healthcare systems, inadequate access to treatment, poor health data control (access to and use of data), lack of a holistic approach, gender inequalities, economic and financial issues. They also noted differences between countries (e.g. low income vs. high income countries) concerning approval of and access to new medicines.

The shared perspectives were synthesised into workable themes/challenges. Workshop participants agreed to focus on challenges related to:

Prioritisation (cost and evidence)

Agreeing on a baseline

Digital health

Fragmentation of healthcare

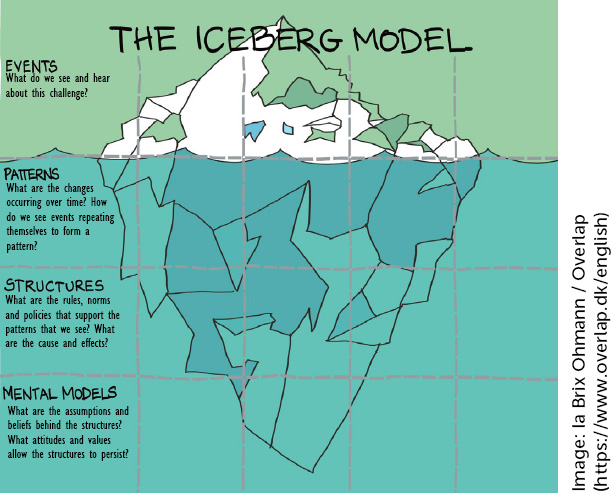

The Iceberg Model was used to identify the factors (events, patterns, structures, and mental models) which should be prioritised for future discussions about potential interventions (Figure 1) [11,12]. The purpose of using this model was to stimulate discussion around not only what we see happening but the potential reasons for it.

Figure 1.

Iceberg Model template used to identify events, patterns, structures and mental models in challenges for access equity.

PRIORITISATION IN TERMS OF COST AND EVIDENCE

1.

Prioritisation relates to the economic and financial challenges of justifying the optimisation of a care pathway for a rare disease within the context of other healthcare priorities. It encompasses the differing priorities of each stakeholder and what evidence is needed to justify them now and in the future. For example, a haemophilia specialist with a patient with hepatitis C will want to prioritise their access to relevant infectious disease care, but the specialist caring for patients with hepatitis C will not expect to prioritise the patient with haemophilia. Such variation in priorities can be found across different areas of expertise in the healthcare system, even when guidelines and other official provisions indicate the importance of rapid access for specific patient groups [13].

In determining priorities, healthcare systems currently focus heavily on cost. Despite the fact that the lived experience of patients can provide important insights [14,15], including greater understanding of the burden of standard of care, this is frequently overlooked. Cost-effectiveness calculations often focus on direct hospital costs with little emphasis on the many indirect costs to patients and their families in the community [16]. Innovation is rarely incorporated into pathways as it is considered unaffordable, and cost-effectiveness models are particularly difficult to apply to rare diseases because there are often too few treatments with which to compare a novel therapy [17]. With the arrival of one-off gene therapies, which will most likely bear high price tags, there are many unanswered questions about the evidence needed to support their cost-effectiveness and value compared with current lifelong treatments [18,19]. It is anticipated that the economic aspect will be a barrier to accessing these therapies.

Although it is recognised that patients should be involved in the development of rare disease care pathways [8,20], their involvement and that of advocacy groups is not consistent. A comprehensive and nuanced view, representing the views and needs of the wider patient population, may therefore be limited or missing when it comes to designing health systems and prioritising patient needs [21].

Additionally, development and improvement of patient support may be impacted by a lack of assessment of care pathways, including by patients themselves. This is particularly evident in the transition from paediatric to adult care, a pathway identified as being particularly challenging in terms of ensuring smooth access to and continuity of care.

Haemophilia and other rare bleeding disorders are among the rare diseases where comprehensive care based on a multidisciplinary approach is acknowledged as being the gold standard for treatment [22]. However, resource allocation for multidisciplinary care may be impacted by fragmentation in funding models [23], combined with which there may be issues in ensuring key professionals are available within the multidisciplinary team [24]. In rare disease care pathways, lack of specialists and volume of patients also make it difficult to prioritise elements of ‘layered care’ (i.e. the simultaneous provision of different types of care). There is limited understanding of the impact of this more holistic approach to care, and of the need for pathway flexibility – given that homogeneous pathways do not ‘fit’ rare diseases. In many cases, patients find themselves having to coordinate access to different health care professionals (HCPs) [25], which can be even more complex for older patients with comorbidities. Paying for multiple consultations and follow-up is also an issue. Even where rare disease care pathways are established in principle, the reality may differ from agreed practices and only a limited number of patients may benefit [13]. Where health services are decentralised – for example, in countries where healthcare is organised at regional or provincial level – this adds a further layer of difficulty to implementing care pathways and contributes to poorer patient access and increased burden [26].

AGREEING ON A BASELINE

2.

Baseline care is a minimum, safe standard that should be provided for patients wherever they live. Existing standards of care for rare diseases, e.g. the European Principles of Haemophilia Care developed jointly by patients and HCPs [27], can inform the establishment of a baseline for care pathways. The challenge, as outlined above, lies in addressing variability at every level, from patient disease to healthcare resources, in order to tailor pathways to local needs. One size will not fit all.

As a first step to agreeing a baseline, it is helpful to break the patient journey down into four key stages:

At each stage, a baseline pathway should be agreed, based on safety and best practice, and with specific desired health outcomes for each intervention [28]. The patterns, structures and mental models that impact each stage are considered here with reference to bleeding disorders as an example of a rare disease area.

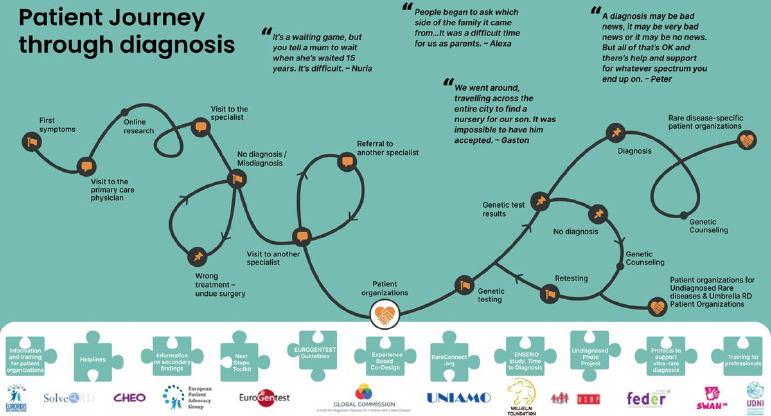

It is well established that people with rare diseases face increased difficulties in getting a diagnosis, making this a complex and potentially frustrating stage in the patient journey (Figure 2). These are typically linked to the rarity of the disease, lack of awareness among general practitioners and non-specialist HCPs, and a lack of medical expertise and resources to carry out the diagnosis [29]. Gender inequality and discrimination in healthcare may play a role in delaying diagnosis, as has been shown in rare bleeding disorders [30,31]. Geographical disparities are also a consideration – for example, where a patient lives at a distance from an expert treatment centre – impacting out-of-pocket expenses for those accessing diagnosis, and automatically discriminating against people on lower incomes or living in more remote areas.

Figure 2.

Infographic showing the patient journey to diagnosis in rare diseases, developed as part of the EURORDIS Solve-RD project [32]

Haemophilia is a relatively fortunate rare disease in the sense that many treatment options exist and that they are available for people living in higher-income countries. These diverse treatment options can make it difficult to agree on a baseline for the third stage of the patient journey, especially with the introduction of expensive, innovative therapies such as gene therapies, though it should be noted that these are not currently offered to children. Continued research is needed to fill gaps in evidence to support the cost-effectiveness of novel treatments. This is not without precedent: again using the example of haemophilia care, some healthcare providers initially assumed they could not afford to provide prophylaxis, but comparative studies with on-demand treatment demonstrating its costeffectiveness helped to change mindsets [33].

There is increasing recognition that patient lived experience and preference should influence treatment choice, wherever choices are available. Shared decisionmaking should therefore be a key element in setting the baseline standard for treatment. This may also support improved treatment compliance – and, in doing so, potentially support treatment cost-effectiveness and reduce waste of resources – but patient education and good therapeutic relationships with HCPs are also key to achieving this [34]. The multidisciplinary team should also be incorporated into the shared decisionmaking process, with the various medical specialties represented being included in ongoing monitoring and re-assessment of the treatment protocol. Many of the challenges of setting a baseline during the monitoring and follow-up stage of the pathway are similar to those in the earlier phases. Again, different healthcare systems and resources, different bodies of evidence and gaps in evidence need to be addressed in setting a baseline.

DIGITAL HEALTH

3.

Digitalisation is one of the leading trends in the healthcare sector [35], with digital health and artificial intelligence (AI) being presented as potential solutions to increasing cost-effectiveness. This is at a time where health care budgets are squeezed and governments are struggling with retention of the healthcare workforce due to burnout and discontentment with working conditions. Legal frameworks for the rollout of digital health and AI solutions in healthcare are currently being assessed at the European level via the European Health Data Space [36] and the AI Act [37]. The outcomes of these two legislative developments will heavily impact the way in which digital tools will be used in a healthcare setting, from diagnosis to monitoring and patient assessment. However questions remain, including how these tools will be designed, whether patient preferences and perspectives will be incorporated, and data privacy concerns. In addition, from a technical and infrastructural perspective, significant limitations remain with regard to data collection, transfer and security, alongside issues around confidentiality and data ownership [38]. Here, digital health will be assessed from three key perspectives: the patient, healthcare providers and payers.

For the patient, digital health offers opportunities such as monitoring health via apps, potentially including patient-reported outcomes [39]. However, there may be issues associated with digital literacy, adherence to engaging with digital tools, and the perceived personal value to the patient [40]. Integration of collected data into other digital health systems may be challenging, and if the data is not standardised and validated it may prove of little use for research or economic assessment purposes. There are also questions around data privacy and the secondary use of patient health data. In addition, not all patients are interested in sharing their data or using technological solutions to monitor their treatment, and some may not engage with healthcare systems. Reluctance or excitement about technology from the actors in healthcare systems mirrors the diverse attitudes found in wider society.

Digital systems for healthcare providers are often developed in silos, meaning they cannot be accessed across hospitals or, in some cases, even across departments within a hospital [41]. Digital health systems and apps should be built to allow effective integration and sharing of data, but to date this has generally not been the case. Having digital technology is only the start, and considerable time and energy are needed to make it work effectively. HCPs may not feel motivated to engage with the technology and collect and pass on data. This data is also valuable and healthcare providers may be reluctant to share it unless their efforts are recognised financially.

For payers, health economics is fundamental to any decisions about digital health [42]. Rising levels of chronic disease and high healthcare costs mean that payers are interested in digital tools to provide data at all stages of the disease journey that indicate what is needed to reduce the economic burden [43].

With the exception of data security, which is a challenge for patients, healthcare providers and payers, there is little overlap in the value propositions being used to drive progress. There is a lack of agreement about how digital health can facilitate future care pathways and significant questions related to cost, e.g. how much healthcare providers and payers are willing to pay, and how sharing of data can be reimbursed. Should data-driven models be used to achieve better outcomes or greater economic gain? Population health models are needed to move to new systems that bring value back to the users.

FRAGMENTATION OF HEALTHCARE

4.

People with rare diseases may access care pathways through multiple entry points in primary and secondary care, with significant risk of fragmentation of care [8,44]. Lack of awareness of a given rare disease due to low prevalence may contribute to this fragmentation. Patients rarely experience holistic care that takes account of all their healthcare needs – not only related to their bleeding disorder but also to their comorbidities and life stages (e.g. fertility, pregnancy, age-related comorbidities). For example, the care pathway for a pregnant woman with a bleeding disorder should involve at least three hospital specialties (haematology, gynaecology and obstetrics), as well as primary care [45], but failure to adequately share information about the implications of the bleeding disorder may result in a lack of joined-up care.

Lack of resources is an obvious contributor to pathway fragmentation and issues may arise both in establishing pathways and in losing aspects of care if funding is withdrawn. Whether or not resources are available, recommendations may be misinterpreted. Thus, a pathway may recommend physiotherapy as part of haemophilia care but not stipulate frequency and duration, so one provider interprets this as four or five sessions per month, while another may interpret it as occasional or only in response to bleeds.

Poor communication at multiple levels (e.g. between clinical stakeholders and between clinicians and patients) can result in fragmentation of care. Moreover, lack of health literacy and agency may prevent patients from establishing whether they are missing out on elements of care pathways, and professional attitudes may not encourage patient self-advocacy or respect ‘differences’ [46,47]. Patients from minority groups may struggle to communicate their preferences and needs, and family interpreters may be used when language barriers prevent patients communicating their preferences to clinicians directly. These elements can contribute to fragmentation as care decisions may be affected by family fears, prejudices and beliefs [48].

Although care pathways should be designed to optimise patient care, a lack of flexibility and an inability to adapt to individual patient needs may result in patients receiving less adequate treatment and care. Similarly, if inappropriate assumptions are made, proposed pathways may fail to take account of availability of services/ therapies (e.g. in low- and middle-income countries), resulting in fragmentation where aspects of care cannot be provided.

Care pathways may be focused on clinical aspects of care but exclude opportunities for the psychological support patients may need, related to life changes (e.g. infertility, miscarriage and stillbirth, issues in relationships, the impact of living with a chronic condition on mental health, social life and/or life choices), as well as their disorder [8]. Fragmentation may also arise when care pathways make provision for health issues already present when patients access care, but do not respond to issues arising when the patient is already on the pathway.

CONCLUSIONS

There are well documented advantages to clearly defined, evidence-based care pathways. However, development of future pathways for people with rare diseases will need to address multiple challenges related to prioritisation, minimum levels of care and fragmentation of services, while considering the opportunities and drawbacks of digital health. Future care pathways will need to take account of wide variation not only in patients’ disease pathology, evolving needs and comorbidities, but also the significant national and regional differences in availability of skills, services and resources. Cost cannot be ignored but greater emphasis needs to be placed on patient experience, and research is needed to fill gaps in evidence to support the cost effectiveness and value of innovative interventions.

THE EHC THINK TANK

The European Haemophilia Consortium (EHC) Think Tank was launched in June 2021 Building on existing advocacy activities, the initiative brings together a broad group of stakeholders to engage with key thematic areas or workstreams identified as priority areas for ‘systems change’ within European healthcare systems [49]. The EHC Think Tanks seeks to mobilise the agency and purpose of all stakeholders in the healthcare system to collectively design and champion potential solutions to existing problems.

Workstream members are invited based on their expertise and potential for constructive engagement, including patient and industry perspectives alongside a balance of healthcare professional, academic, regulatory, governmental and geographical representation. All workstream activities are held under the Chatham House rule to enable inclusive and open discussion: participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speakers, nor that of any other participant, may be revealed [50]. Each is projectmanaged from within its individual membership. Members set their own agendas, timelines, and targeted outputs, with operational, logistical, methodological and facilitation support from EHC staff and Think Tank practitioners. While concrete outcomes and results will vary across workstreams, they are likely to include (but not be limited to) manuscripts, consensus-based guidelines, monographs, white papers, and so on.

Since the Think Tank’s inaugural workstream meetings in 2021, the following key topic areas have been the subject of ongoing discussion:

2023 sees the introduction of two new workstreams: