Haemophilia is a congenital coagulopathy with recessive inheritance associated to the X-chromosome. Factor VIII deficiency (haemophilia A) affects approximately 1 in 6,000 men while factor IX deficiency (haemophilia B) affects 1 in 30,000 men. The severity depends on the blood level of the corresponding factor. Appropriate treatment can help to decrease bleeding episodes as well as the acute and long complications of haemophilia, improving survival and the patients’ quality of life [1,2].

RED LAPI was established in 2010 by a group of experienced haemophilia physicians with the aim of assessing haemophilia care in Latin America countries with respect to diagnosis, treatment and quality of life, in order to identify mechanisms to improve care.

The benefits of primary and secondary prophylaxis in preventing arthropathy and bleeding episodes are now well established [3] and widely accepted by international and national organisations [4,5]. However, according to the World Hemophilia Federation, around 75% of peopple with haemophilia worldwide remain undiagnosed, and most of the remaining 25% either do not receive treatment or do not receive the appropriate treatment. There is a further issue around the diagnosis and management of haemophilia patients with inhibitors. Inhibitors are now considered to be the most serious complication affecting haemophilia patients, at least in developed countries where arthropathy has been partially overcome [6]. Inhibitor incidence in studies ranges between 10% and 40% [7]. The presence of an inhibitor complicates treatment with clotting factors, leading to a deterioration in quality of life and a greater risk for development of progressive arthropathy in target joints, increasing the cost of treatment and decreasing patient survival and quality of life [8].

Inhibitors mainly develop in childhood during the first exposures to clotting factor. A quarter of inhibitors are temporary [9]. In 30% of cases inhibitors have a low titer (<5BU), in these patients bleeding episodes are managed with higher doses of clotting factor. The remaining 70% are high titer inhibitors, where factor VIII confers less clinical benefit, requiring concomitant treatment of bleeding episodes with bypassing agents to achieve haemostasis.

In patients with a high titer inhibitor and those with a low titer but persistent inhibitor, immune tolerance induction (ITI) is the only proven treatment to eradicate the inhibitor [10]. At present, there is no consensus on the ideal protocol. Several studies have shown that high dosages of factor (the Bonn protocol, 1994) have the advantage of obtaining a quicker response and a reduced frequency of bleeding episodes [11,12]. Similarly, many studies have suggested a better response to the use of plasma-derived clotting factors containing the von Willebrand factor, which seems to shorten the treatment duration [13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21].

Although ITI is costly, pharmacoeconomic studies have shown it to be less expensive than to treat patients indefinitely with bypassing agents [22].

This paper summarises the current approach to diagnosis and management of haemophilia patients in the 13 Latin American countries taking part in RED LAPI, and proposes actions that are likely to lead to improvement and a positive impact in the quality of life of patients with haemophilia.

Additional aims are to:

Determine the number of haemophilia patients from each country and summarise the numbers of patients on prophylaxis, the type of factor treatment and regimens used

Identify the number of patients with inhibitors and to show the use of ITI for inhibitor eradication.

Materials and Methods

The information was collected using a 27-item questionnaire completed by physician members of RED LAPI, to obtain representative information of each country. The questionnaires sought details of the number of haemophilia patients, existing laboratory evidence, reference centers, treatment type, primary and secondary prophylaxis, inhibitor presence and ITI treatment. Each RED LAPI participant answered the inquiry based on the sources available in their respective countries (Table 1).

Table 1

Information sources

Results

Based on national data, the 13 countries include a total of 225,290,000 inhabitants. At an overall prevalence rate of 1 for each 6000 males some 18,774 patients with haemophilia would therefore be expected. In fact, only 11,556 diagnosed patients were documented (Table 2), suggesting that around 38% of patients from these countries remain undiagnosed.

Table 2

Demographic and diagnostic information on patients with haemophilia A

| Chile | Honduras | Uruguay | Argentina | Venezuela | Ecuador | Peru | Paraguay | Bolivia | Colombia | Panama | Guatamala | Dom | Rep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (m) | 16.5 | 7.8 | 3.3 | 42.2 | 27.9 | 14 | 30 | 6.5 | 10 | 44 | 3.25 | 12.7 | 9.9 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| HTCs (n) | 32 | 2 | 2 | 26 | 23 | 8 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 60 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| National programme? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Estimated* patients with haemophilia A (n) | 1,375 | 650 | 275 | 2,380 | 2,325 | 1,167 | 2,500 | 528 | 833 | 3,667 | 271 | 1,058 | 792 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Diagnosed patients with haemophilia A (n) | 1,300 | 210 | 234 | 2,075 | 2,005 | 104 | 820 | 241 | 118 | 2,500 | 272 | 303 | 267 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Likely rate of undiagnosis (%) | 5% | 55% | 16% | 13% | 14% | 91% | 67% | 54% | 86% | 32% | 0% | 71% | 66% | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Mean consumption FVIII (IU) per capita | 2.49 | N/A | 2.4 | 0.51 | N/A | 0.59 | N/A | 0.51 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0. 5 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Number of adult haematologists (n) | N/A | 6 | 5 | 600 | 15 | 30 | 10 | 18 | 20 | 150 | 29 | N/A | 36 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Number of paediatric haematologists (n) | N/A | 6 | 4 | 200 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 20 | 7 | N/A | 14 | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| FVIII/FIX blood level quantification | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Anti-FVIII inhibitor quantification | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Reference laboratory | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| FVIII genetic analysis | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

Only 6 of the 13 countries have a national registry program designed to record haemophilia management. All but Bolivia have the resources available to diagnose haemophilia, and all but Ecuador, Paraguay and Bolivia are able to diagnose inhibitors. Over half of the countries had at least one reference laboratory but only a third possess the resources to perform genetic analysis (Table 2). Haematologists, internal medicine doctors and paediatricians coordinate diagnosis and treatment of haemophilia in the participating countries.

Concerning treatment, in six of the 13 countries a proportion of patients (ranging from 2 to 80%) are still receiving plasma or cryoprecipitate (Table 3). Among those treated with clotting factors, 69% of patients receive plasma-derived concentrates and 31% receive recombinant factors.

Table 3

Treatment-related information on patients diagnosed with haemophilia A

| Chile | Honduras | Uruguay | Argentina | Venezuela | Ecuador | Peru | Paraguay | Bolivia | Colombia | Panama | Guatamala | Dom | Rep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients on no treatment (%) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | N/A | 80% | 75% | 10% | <5% | N/A | N/A | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Patients treated with cryoprecipitate or plasma (%) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 64% | 0% | N/A | 2% | 0% | N/A | 0% | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Patients treated with clotting factors (%) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 93% | 100% | 100% | 36% | 46% | N/A | 98% | 100% | N/A | N/A | |

| • Plasma-derived (%) | 100% | 100% | 98.3% | 75% | 30% | 99% | 100% | 100% | N/A | 70% | 95% | 70% | 30% | |

| • Recombinant (%) | 0% | 0% | 1.7% | 24% | 70% | 1% | 0% | 0% | N/A | 30% | 5% | 30% | 70% | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Proportion on prophylaxis | N/A | 0% | 25% | 20% | 5% | 10% | 100%† | 31% | 0% | 20% | 100% | N/A | 0% | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Is there access to primary prophylaxis for infants under 2 years? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | N/A | 0% | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Percentage of patients with inhibitor | ||||||||||||||

| Haemophilia A | N/A | 0.3% | 3.5% | 15% | 6.9% | 0% | 3% | 1.4% | N/A | 5% | N/A | N/A | 0.3% | |

| Haemophilia B | 0% | 0% | 0.4% | 1.5% | 1% | 0% | 0% | N/A | N/A | 1% | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Is there access to bypassing agents for bleeds in patients with inhibitors? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes* | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Is there access to ITI? | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes* | No | No | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | |

Despite the existence in most countries of a national recommendation that newly diagnosed severe haemophilia patients should be managed by prophylaxis, the overall percentage of patients who receive prophylaxis is just 12%, which corresponds to about 1,400 patients across the 13 countries. Based on the number of diagnosed haemophilia patients, about 6,000 would be expected to be receiving prophylaxis. Half of the countries are now implementing primary prophylaxis for newly diagnosed children, but most patients are receiving secondary prophylaxis.

Many studies have shown the importance of haemophilia patients receiving care from a specialised treatment centre as part of a comprehensive care program [23,24]. Only five countries from the region fully cover patients’ treatment (Chile, Venezuela, Uruguay, Argentina and Colombia), and of these, only Chile, Venezuela and Uruguay offer comprehensive national haemophilia management programmes. Other countries have local programs that provide treatment to a segment of the population.

Discussion

Most of the Latin American countries participating in RED LAPI do not have a national haemophilia programme and national patient registry. Even in those countries where such a programme exists, haemophilia coverage is not routine for all patients. For this reason it is extremely difficult to obtain precise data: much of the data available through RED LAPI is only approximate as it has not been collected systematically. Generally, for economic reasons, Latin American countries have limited healthcare budgets and governments are often forced to prioritise resources to those programmes that benefit larger numbers of patients and produce a bigger impact on the health of the population, such as antenatal care, vaccination, family planning, nutrition, and so on [2]. Programmes to support rare, high cost illnesses such as haemophilia are frequently absent or are only partially covered by governments.

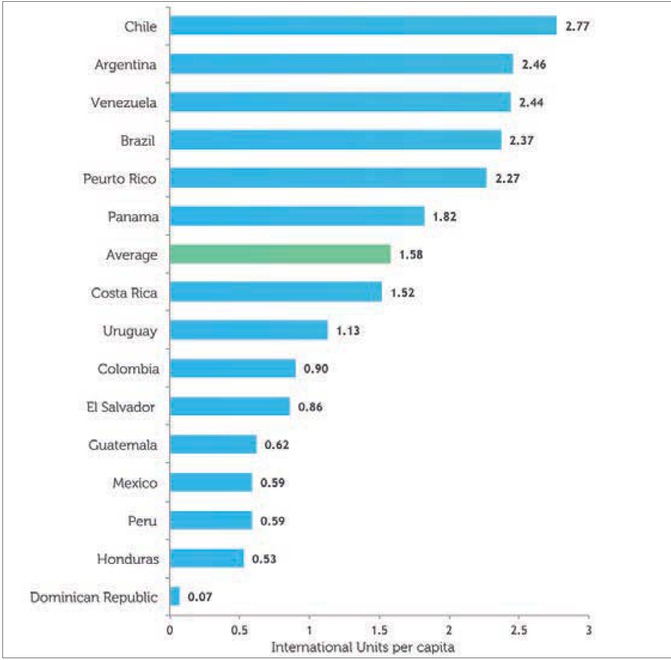

According to data from the Marketing Research Bureau lnc (published in March 2012), none of the countries participating in RED LAPI achieved the World Federation of Hemophilia recommendation of 3-4 IU FVIII/per capita (Figure 1). While three countries (Argentina, Venezuela and Chile) achieved per capita factor VIII consumption in excess of 2 IU, consumption in Uruguay and Panama was between 1 and 2 IU per capita; it was between 0.5 and 1 IU per capita in Colombia, Guatemala, Peru, Ecuador and Honduras, and less than 0.5 IU per capita in Dominican Republic and Bolivia.

Figure 1

Average consumption of factor VIII (plasma-derived and recombinant) by country, 2010 (International Units per Capita). Data from The Marketing Research Bureau, Inc

It is extremely important that physicians and patient advocates raise awareness of the benefits of improved haemophilia management among those responsible for health-related decision-making. Investment in the management of haemophilia can significantly improve patients’ quality of life and reduce the risk of disabilities in adult life, thereby reducing long-term costs. Furthermore, primary prophylaxis and ITI are cost-effective and can dramatically impact on patient’s quality of life.

It is imperative to improve the diagnosis of all the patients in these countries, in order that patients may receive appropriate treatment. While none of the Latin American countries are in an ideal position to diagnose and care for haemophilia patients, it is clear that the situation in some countries is in urgent need of improvement, as many patients are not classified and receive no treatment at all. Those countries within the region that do operate haemophilia programmes show that it is possible to improve the care of these patients even when resources are limited.

It seems probable that more than a third of patients, perhaps as many as 7,000 individuals, have haemophilia but have never been diagnosed. Many of these patients probably have a less severe form of haemophilia. Nevertheless, even mild haemophilia patients and carriers need medical help in the same way as severe patients. Mild haemophilia is associated with a higher morbidity and mortality, due to underestimation of the potential risk of bleeding in the event of surgical procedures or trauma. Therefore, it is essential to continue advocacy and health education work, so that all patients with coagulation disturbances can be identified and managed by specialists.

It is recommended to improve patients’ access to diagnostic laboratories. Indeed, these laboratories need to be properly equipped, and staffed by trained personel, and to be subject to internal and external validation and certification.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of haemophilia presents a challenge to all Latin American countries. Although some countries have diagnosis levels similar to those of developed countries, others have no means of analysis for coagulation factor assays.

There is a similar level of heterogeneity with respect to the availability of treatment. While some countries treat patients with recombinant factors and/or high purity plasma factors with or without von Willebrand factor, there are also some countries or population segments that lack access to treatment of any form, and rely solely on blood components.

The RED LAPI professional team works with the purpose of contributing and improving the diagnosis and treatment of haemophilia in Latin America. We consider that the actual panorama of haemophilia in the 13 Latin American countries represented in this work should be the starting point to develop activities that produce a significant change in the patient’s quality of life. To this end, RED LAPI has been carrying out training activities for doctors, nurses, technicians and patients in Argentina, Ecuador and Colombia.