Education and support during the shared decision-making process is key to ensuring that people with haemophilia are able to make informed therapeutic choices as gene therapy becomes more widely available as a treatment option

Shared decision-making (SDM) is a process by which healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients or their caregivers jointly reach a decision about care, described in haemophilia care by Athale et al. in 2014 as a two-sided intervention including tools to aid patient decision-making [1]. As such, it forms a core part of patient-centred care [2].

Approaches to SDM vary according to its context, including both generic models and models developed for specific healthcare settings [3,4]. However, in all contexts, it is based on a two-way exchange and synthesis of information between HCP and patient, recognising the combined value of the medical knowledge of the HCP and the experiential knowledge of the patient [3,5]. The exchange should encompass clinical evidence and individual patient/caregiver preferences, beliefs and values, and must include consideration of the risks, benefits and possible consequences of different treatment options [2]. The patient/caregiver must understand these and the range of therapeutic options available to them; the HCP must be equipped to provide information to the patient/ caregiver to support their understanding. While SDM is widely recommended in healthcare policy, the extent to which it is truly practised is unclear [6,7].

WHY IS SHARED DECISION-MAKING IMPORTANT IN HAEMOPHILIA CARE?

For many years, the choices for healthcare providers around haemophilia treatment options have been relatively simple: treatment on-demand to replace the missing coagulation factor when bleeds occur or, for people with severe haemophilia who bleed more frequently, initiating prophylaxis where sufficient factor concentrates are available [8]. The choice of treatment product, until recently, was limited to plasma-derived or recombinant products. Reducing the number of bleeds experienced was the greatest priority for people with haemophilia (PwH) [9], although the frequency of infusions under a prophylactic regimen led to greater treatment burden. Over time, the introduction of personalised prophylaxis, the modification of coagulation factor molecules to facilitate longer-acting treatments, and the development of non-factor replacement therapies have contributed to reducing this burden [10,11].

As contemporary haemophilia care has moved from factor replacement to novel therapies [12] and gene therapy [13], identifying the optimal haemophilia treatment for an individual is now a ‘difficult and multifaceted process’ [14]. It is therefore important that PwH and their families are involved in decisions around their care in an ‘informed and interactive way’. Ensuring that bleed protection continues is essential but must be considered alongside the hopes and expectations of PwH with regard to new treatments. Healthcare providers must also recognise that, as patients with a long-term condition, PwH have acquired expertise through their own lived experiences and may have differing opinions about treatment from those of their healthcare providers [15].

SHARED DECISION-MAKING AND GENE THERAPY FOR HAEMOPHILIA

Gene therapy is a new therapeutic option that may become part of routine clinical care for haemophilia. The nature of haemophilia gene therapy necessitates a commitment to a long-term treatment journey on the part of the patient, as once the vector is infused, it cannot be removed. It is a one-time only, irreversible treatment. In this context, SDM becomes both more complex and more necessary.

PwH need to be well informed about the process of gene therapy and must be enabled to engage in fully informed decision-making and consent [16]. Issues around long-term durability of factor expression and potential side effects (which are not fully known) must be understood by PwH. It is not possible to predict outcomes for haemophilia gene therapy, and a good initial response does not preclude loss of expression leading to reduced factor expression or failure of gene therapy [17]. Data on longer-term outcomes remain unknown at present due to the limited long term follow up of PwH in gene therapy trials. The known side effects of gene therapy currently include infusion related reactions, liver function abnormality or toxicity, and side effects of corticosteroids or other immunosuppression [17]. There is a theoretical risk of integration of the vector into the host genome which may predispose to malignancy [18]. Currently immune response to the vector, inducing vector antibody formation, means that re-dosing with the same vector is not possible[17]. Potential recipients of gene therapy must understand the risks and the need for long-term (potentially lifelong) follow-up within their decision-making process. It is, therefore, imperative that the understanding and expectations of PwH are central to all discussions about gene therapy as a treatment option, including ‘unknown unknowns’ about long-term impact [19].

HCPs and patient organisations both have a role in guiding and supporting PwH through their decisions around gene therapy as a treatment option [20], enabling them to be a full partner in the decision-making process [14,21]. This should include ensuring that they are empowered to choose not to have gene therapy at any time in their gene therapy journey prior to infusion [22]. There is an assumption that HCPs will be able to support non-biased shared decision making. Valentino et al. [23] recommend the provision of education and training around SDM for all those who ‘evaluate, administer and follow’ candidates who may receive haemophilia gene therapy. This is important in minimising potential therapeutic biases that could result in HCPs who do not perceive benefits of gene therapy swaying SDM and vice versa, and unconscious bias linked with the ethnicity, culture or educational level of individual PwH [2].

Patient preferences must be understood in order to ensure decision-making that supports the individual situations of PwH. Within this, it is important to understand the cognitive biases that the patient may also bring to the SDM process [24]. Attentional bias, for example, may lead to a selective focus on the benefits of gene therapy versus the risks or vice versa [22]. Social biases may include the influence of family members who have different treatment preferences; and as gene therapy is a new mode of treatment, familial and community links with the contaminated blood scandal may raise concerns [22,25]. Information or misinformation about gene therapy in the public domain is another potential social bias. Self-perception bias linked with an individual’s view of themselves as a person with haemophilia may also be a factor [22]. SDM provides a framework for discussing patient preferences and values in the context of available evidence [26].

HOW DO WE ENSURE SHARED DECISION-MAKING IS A REALITY?

For PwH to be fully involved in SDM in relation to gene therapy, they must have access to clear, relevant information and education. This should be based on tailored communication to ensure that those with ‘low levels of health literacy or socioeconomic disadvantage’ are not excluded [16,20].

Hermans et al. [14] describe patient involvement and education as two key principles in SDM. This includes a focus on ‘what really matters to patients and families in terms of treatment priorities, expectations and ambitions’, and the use of ‘jargon-free terminology’. All members of the healthcare team should be educated about new treatment options in order to be able to support PwH through the SDM process.

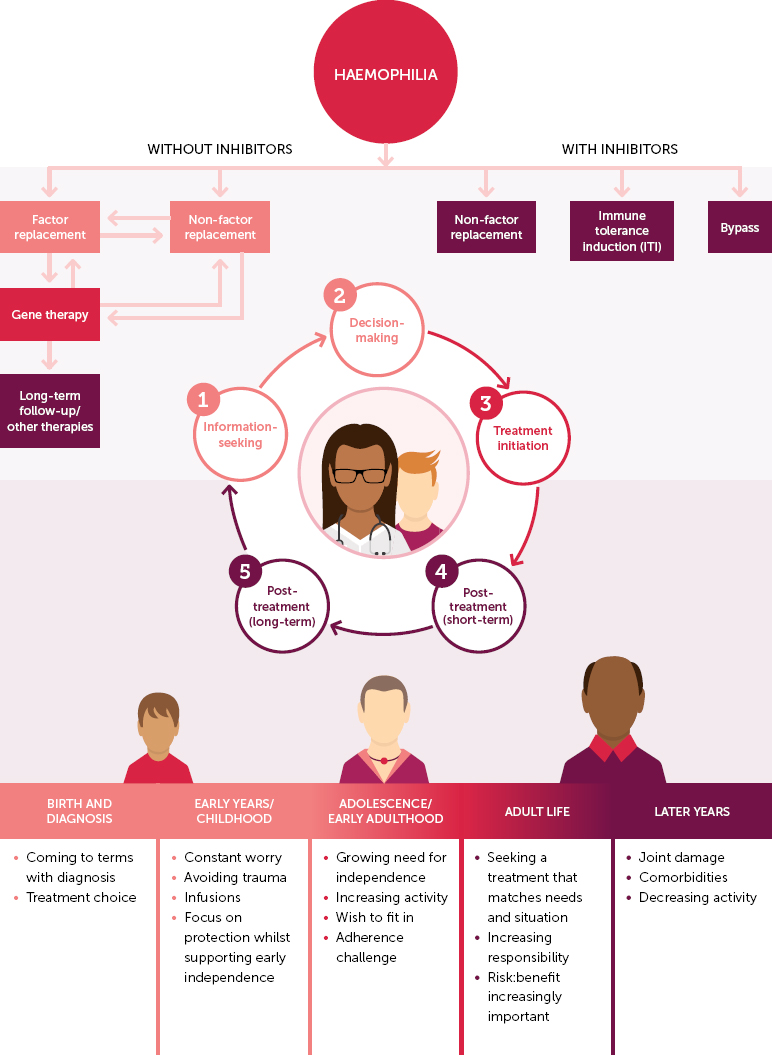

Supporting PwH in decision-making around gene therapy as a treatment option is a process (or journey) that may take a considerable amount of time from first discussion to dosing [21]. Wang et al. describe five pillars of the decision-making journey: ‘pre-gene therapy information seeking’, ‘pre-gene therapy decision-making’, ‘treatment initiation’, short-term post-gene therapy follow-up (≤ 1 year)’, long-term post-gene therapy follow-up (> 1 year)’ [19]. All of these elements must be considered when embarking on SDM discussions around haemophilia gene therapy and the process must not be rushed. Gene therapy is a complex treatment that, due to its nature, involves a complex and multifaceted decision-making journey that will be different for each individual (Figure 1). PwH will therefore require considerable education and support before they are able to make a truly informed decision.

Figure 1.

The patient decision-making journey in the current treatment landscape (cf. Wang et al., 2022) [19]

The use of SDM structured tools to support patient decision-making is recommended as good practice [6]. The SHARE approach, designed by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, is commonly cited as an appropriate model in the context of haemophilia gene therapy [2,20,21]. This five-stage process is based on ‘Seeking patients’ participation, Helping patients explore and compare management options, Assessing patients’ values and preferences, Reaching a decision with patients, and Evaluating the patient’s decision’ [27]. While this model provides an important point of reference for the role and responsibilities of HCPs in SDM, it assumes that interaction is led by the HCP rather than the patient. However, the discussions that occur as part of the SDM process do not necessarily have to begin with HCPs. PwH may seek to initiate conversations around gene therapy, including SDM, and it is important that HCPs foster an environment in which this can happen. In either case, PwH must also be aware of their role in the SDM process, including education (supported by the HCP), careful consideration of benefits and risks, and open communication with the HCP around treatment goals and preferences [28].

There is a need for SDM educational tools that include written/visual information about the benefits and risks of gene therapy treatment, expectations and realities, and the need for long-term monitoring and follow-up [14,16,21]. Standardised checklists may be helpful for both PwH and HCPs, within and outside of the clinical setting. Having a point of reference of this kind can help to ensure that all elements that need to be discussed in clinic are discussed [18]. In the US, Limjoco and Thornburg have consulted people with haemophilia A and HCPs on the development of an SDM tool or tools for gene therapy, incorporating a checklist and taking both perspectives into account [29,30]. PwH felt that having access to an SDM tool laying out the pros and cons of gene therapy would support their decision-making outside of clinic through enabling further review and discussion with their families. The proposed checklist included education about gene therapy, risks, comparison with other treatments, follow up, impact on mental health and quality of life [29]. A tool aimed at facilitating HCP discussion has been developed, which can be used during patient discussions on gene therapy in combination with the SDM tool developed by the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) [27,30,31]. The WFH SDM tool is designed to assist with treatment selection and includes a significant number of downloadable patient education materials comparing currently available treatments alongside gene therapy [31]. It describes the SDM journey of reflecting on current personal goals and available treatments, considering future options and confirming a decision about treatment. As this tool will be widely accessible, it has the potential to support both HCP and PwH through the decisionmaking process. Going forward, the role and value of tools such as these should continue to be assessed from the perspectives of both PwH and healthcare providers [16,20].

For some PwH, SDM may be a new concept. They may have had little engagement in decision-making about their treatment previously and may perceive SDM as an intimidating prospect [2]. Patient organisations can play a valuable role in respect of both explaining new treatment paradigms such as gene therapy and supporting PwH in SDM [20]. This may include, for example, providing educational materials that support health literacy [16] and peer support groups to facilitate discussion about the process of gene therapy [21]. Support should be available for PwH for whom gene therapy proves not to be an accessible treatment option [32], and for PwH who would like to have gene therapy but whose choice is not supported by their healthcare provider or organisational policies.

CONCLUSION

SDM is an important aspect of haemophilia care and is a necessity as gene therapy becomes a more widely available treatment option. With haemophilia gene therapy, healthcare professionals are asking PwH to make decisions about a treatment that may not work as well as they had hoped, that can currently only be undertaken once, and for which we cannot offer long-term safety guarantees. It is therefore essential that they are equipped with the knowledge, skills and confidence to support SDM. Recent recommendations from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for research around measuring the effectiveness and sustained implementation of SDM in the clinical setting [6] should be considered in the context of haemophilia treatment choices and SDM for haemophilia gene therapy.

Education and support of PwH during the SDM process using currently available and developing SDM tools [27,30,31] are paramount to ensure fully informed individual decision-making and consent. The development of tools to ensure equitable access to education and information about haemophilia gene therapy and the patient journey are now starting to be developed. Patient organisations are key in supporting their members to make appropriate decisions about gene therapy, as well as campaigning for access and funding as these treatments become clinically available. The most important part of this process is that PwH want to undergo gene therapy – and this is only an option if they are fully educated and informed by fully educated and informed healthcare teams.