© Shutterstock/Jakub Zak

Low contamination risk, simplicity of use, convenience and portability were the most important features for reconstitution devices in a survey of PwH and caregivers in the US, Italy, the UK and Japan

It is estimated that over 1.1 million males worldwide currently live with haemophilia [1]. The goal of modern haemophilia management is to prevent spontaneous bleeds, often by replacing missing coagulation factors. Recombinant factors VIII (rFVIII) and IX (rFIX) are recommended as replacement therapy for people with haemophilia A and B, respectively [2]. The factors can be administered at home by people with haemophilia (PwH) themselves or by their caregivers, and usually this involves preparing and administering the appropriate coagulation factor via injection [2,3]. The frequency at which replacement therapy is administered varies depending on the disease severity (severe, moderate, or mild), and for some products the age, factor activity levels, and treatment choice of the PwH [2]. There are two main modes of replacement therapy for PwH: preventive (prophylaxis) and episodic (on-demand). Prophylaxis is vital for people with severe haemophilia as on-demand infusions do not prevent spontaneous bleeding and related complications [2,4,5]. Therefore, prophylaxis is the recommended standard of care, with around 77% of PwH prescribed this mode of therapy [6]. However, prophylactic treatment does carry a substantial burden for PwH and their caregivers as the recommended dosing frequency for standard half-life products is around 2–3 times per week and it can take up to 50 minutes to prepare and administer each dose [7,8].

The first iteration of replacement therapy came in the form of plasma-derived clotting factors. However, transmission of blood-borne viral infections became a significant challenge as PwH were exposed to nonvirally inactivated blood products, highlighting the need for safer treatment options [9,10]. The advent of recombinant clotting factors was revolutionary to the treatment of haemophilia and provided a near unlimited source of clotting factor for this community, without the risk of blood-borne infections [9]. rFVIII was the first recombinant factor to be approved by the FDA, followed soon after by rFIX, providing a safer source of replacement therapy for people with haemophilia A and B, respectively [11,12]. These factors were initially provided as liquid or lyophilised products and could be administered at home; however, risk of needlestick injuries was a concern and the shelf life of such products was limited [13,14]. Further, reconstitution of the lyophilised product prior to administration required additional steps and device components, making the process more complex and time-consuming. These drawbacks are reported to be a major barrier to treatment adherence [3,8,14,15].

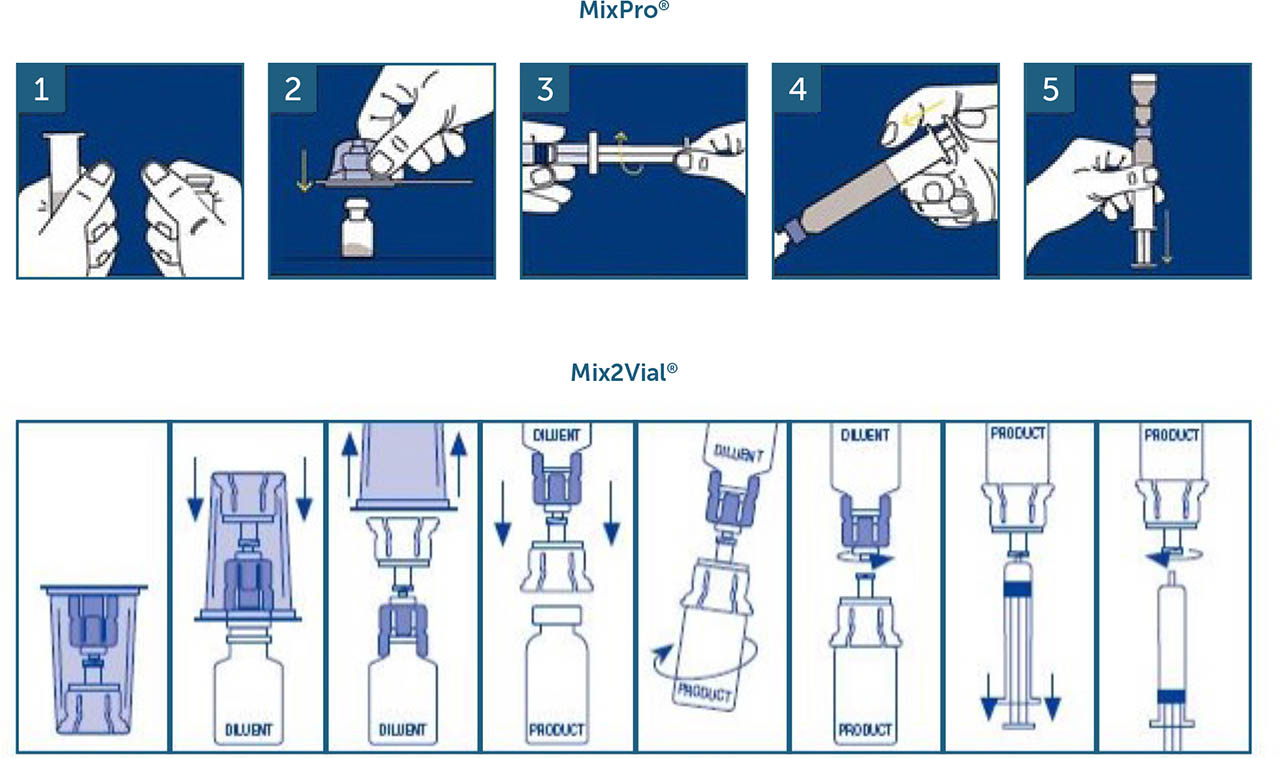

Pre-filled syringes and dual-chamber devices are two examples of modern reconstitution devices developed to reduce the number of steps or components required, making it easier and more convenient for both PwH and caregivers to administer treatment [15,16,17,18]. Mix2Vial® (West Pharmaceutical Services, Exton, PA, USA) and MixPro® (Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsværd, Denmark; design based on a vial adapter from West Pharmaceutical Services) are both drug reconstitution devices currently approved to administer a number of different replacement therapies to PwH (Supplementary Figure 1a). Both devices contain a diluent and lyophilised drug product, and both are needleless, reducing the chance of needlestick injuries during the reconstitution process [17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. However, one key difference between the two devices is that the MixPro® diluent is provided in a pre-filled syringe instead of a separate vial as with Mix2Vial®. This reduces the number of mixing steps required prior to administration and aims to make the reconstitution process more straightforward [3,18]. Two previous publications evaluating MixPro® in PwH and caregivers have suggested that there are benefits to using this device over other existing reconstitution systems. In both studies, MixPro® was perceived favourably and was highly rated in parameters deemed most important in a reconstitution device, with its ease of use and portability highlighted as key advantages [3,16]. However, to date, no direct comparison studies between the MixPro® and Mix2Vial® devices have been performed.

This study aimed to compare the experiences and preferences of PwH and caregivers using MixPro® and Mix2Vial® reconstitution devices.

METHODS

Participants were recruited through a combination of haemophilia patient panels, patient associations and advocacy groups, national databases, and referrals from healthcare professionals over several weeks.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study included people with haemophilia A or B (with or without inhibitors), or caregivers of PwH under the age of 18 years. The PwH or caregivers had to be responsible for the regular infusion of replacement factor to be eligible. Participants were permitted to have previously used both MixPro® and Mix2Vial® devices before the interviews were conducted.

Interviews

This study was designed to evaluate the current unmet needs of today's reconstitution devices and which features of these devices are most important to PwH and caregivers. It also examined how well MixPro® and Mix2Vial® perform on each feature, the overall preference for one device versus the other, and key benefits and drawbacks for each device.

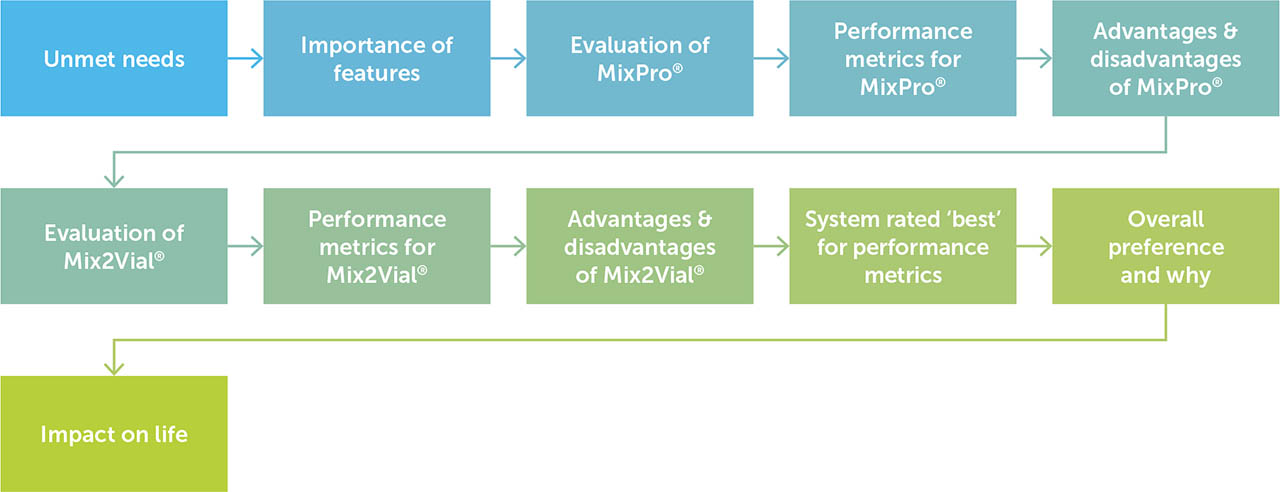

Qualitative structured interviews were conducted face-to-face in a fieldwork agency office in the USA, Europe, or Japan. Interviews were undertaken in person so that all respondents could interact with demonstration MixPro® and Mix2Vial® devices. The interviews were conducted between 22 June 2021 and 4 August 2021, and each interview lasted approximately 30 minutes. The interview flow was predetermined, with each of the two devices being evaluated separately using a random rotation. This resulted in half of the participants evaluating MixPro® first, followed by Mix2Vial®, and the other half evaluating the two devices vice versa. Topics included: unmet needs, importance of features, evaluation of each device including performance metrics and advantages/disadvantages, device best rated for each performance metric, overall preference, and impact on life (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Interview discussion flow

Flow diagram showing the predeterminedd flow of topics for face-to-face interviews. The system evaluated first was randomly rotated for respondents.

To assess unmet needs, participants were asked ‘What, if any, would you say are your biggest unmet needs with your current mixing/reconstitution system?’, prior to being provided with either the MixPro® or Mix2Vial® device. Participants were allowed to provide their thoughts to the question with no prompts from the interviewer. The open-ended answers were then analysed and coded based on the frequency at which different needs were mentioned. Current and past devices used by each participant were also recorded, including whether they had experience using either the MixPro® or Mix2Vial® device.

In order to assess the importance of certain device features, a list of features was adapted from previous studies by the research team [3,16]; it was then further updated and refined following pilot interviews (Supplementary Table 1). The importance of each device feature was derived from a series of exercises with the respondent, followed by analysis of the data. First, participants were asked to perform a card-sort exercise to rank all 18 features from the most to least important. Results from this ranking task were then used in a win-loss analysis (also known as the Bradley-Terry model; B-T) to identify the frequency at which one feature is rated more important than each of the other features [27]. The raw B-T parameter estimates were transformed into a user-friendly form by dividing each attribute's B-T estimate by the sum of the B-T attribute estimates to arrive at a relative importance percentage [28].

Table 1

Study participants

| PARTICIPANT | COUNTRY OF RESIDENCE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWH | CAREGIVERS | USA | ITALY | UK | JAPAN | TOTAL | |

| n | 71 | 34 | 30 | 25 | 30 | 20 | 105 |

| Age, years (range)* | 34 (13–69) | 16 (3–69) | 29 (6–61) | 39 (4–69) | 22 (3–60) | 26 (11–65) | 29 (3–69) |

| Treatment type, n (%) | |||||||

| Prophylaxis | 68 (96) | 34 (100) | 28 (93) | 34 (96) | 30 (100) | 20 (100) | 97 (102) |

| On-demand | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) |

| Type of haemophilia, n (%) | |||||||

| A | 61 (86) | 29 (85) | 26 (87) | 24 (96) | 28 (93) | 12 (60) | 90 (86) |

| B | 10 (14) | 5 (15) | 4 (13) | 1 (4) | 2 (7) | 8 (40) | 15 (14) |

Using the same list of features, respondents were asked to rate each of the two devices on the 18 features using a 7-point scale, where 1= Does not describe the device at all and 7= Completely describes the device. Data are presented as the percentage of respondents that provided a rating of either 6 or 7 for any given feature in the benefits list (top 2 box rating).

A word association exercise was also completed for each of the two devices in which participants were given a list of 26 words (Supplementary Table 2) and asked to select up to eight words that were most associated with the device being assessed. The selected list of words was based on previous studies and revised by the research team for the purpose of this study [3,16]. Data are presented as the percentage of participants who selected a given word. Any word selected by fewer than five participants is not shown.

Once each device was assessed individually, a direct comparison was performed. Using the same 18 device features assessed for importance, participants were asked to indicate which device performed better for each feature. Participants were asked to select one or the other device; ‘neither’ was not given as an option for the answer.

A final overall preference question was asked using a 100-point allocation exercise. Respondents were asked to allocate 100 points between the two devices to demonstrate their level of preference between them.

Statistics

A paired-samples t-test of means was used to compare the data for each device for all feature metrics (where the same respondent rated both devices) to determine statistical significance at a 90% confidence level (commonly accepted for these types of studies).

When testing between two independent groups (such as PwH vs. caregivers or the USA vs. Italy), statistical testing was conducted at the 90% confidence level using an independent samples t-test of proportion.

RESULTS

Participant demographics

In total, 105 participants (71 PwH and 34 caregivers) were interviewed across the USA (n=30), Italy (n=25), UK (n=30), and Japan (n=20). The mean (range) age of PwH represented in this research was 29 (3–69) years, with the highest mean being in Italy at 39 years. The mean age was 34 years for PwH self-administering injections and 16 years for the children of caregivers (Table 1). Almost all PwH (97%) had been prescribed their current medication as a prophylactic and the majority (86%) were diagnosed with haemophilia A (Table 1). Overall, seven participants reported they had previously used or were currently using the MixPro® device and 15 participants had previous or current experience with Mix2Vial®.

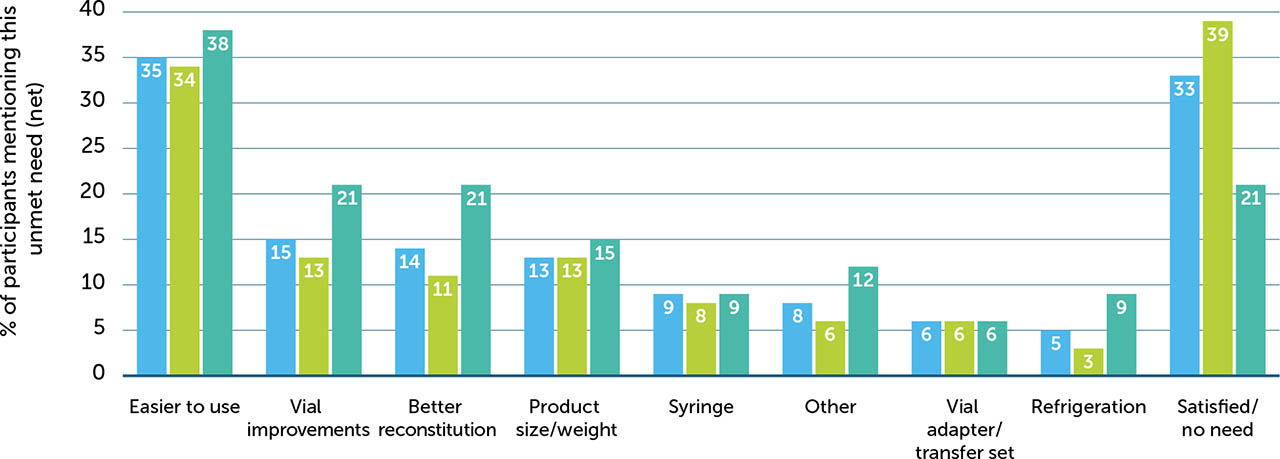

Unmet need

When asked about the biggest unmet needs with their existing reconstitution devices, 33% of participants reported that they were satisfied with the existing device they were using and had no unmet needs. However, 35% of participants described unmet needs relating to the overall ease of use, with specific mentions around the need for fewer parts (12%), faster reconstitution (11%), and being easier to use (7%). Eleven percent of participants stated that existing devices are too big and that less bulky devices would be preferable. Participants also expressed the need for less waste, sturdier components, a better transfer system, and alleviating the need for refrigeration to improve the overall experience with these devices (Supplementary Figure 2). This may be in part due to these participants using older devices and being less familiar with the more streamlined, modern devices used in this study. Thus, the unmet needs reported here are highly subjective and are likely to reflect the drawbacks of whichever device that a participant is currently using which may also reflect the ancillaries provided alongside the device itself.

Importance

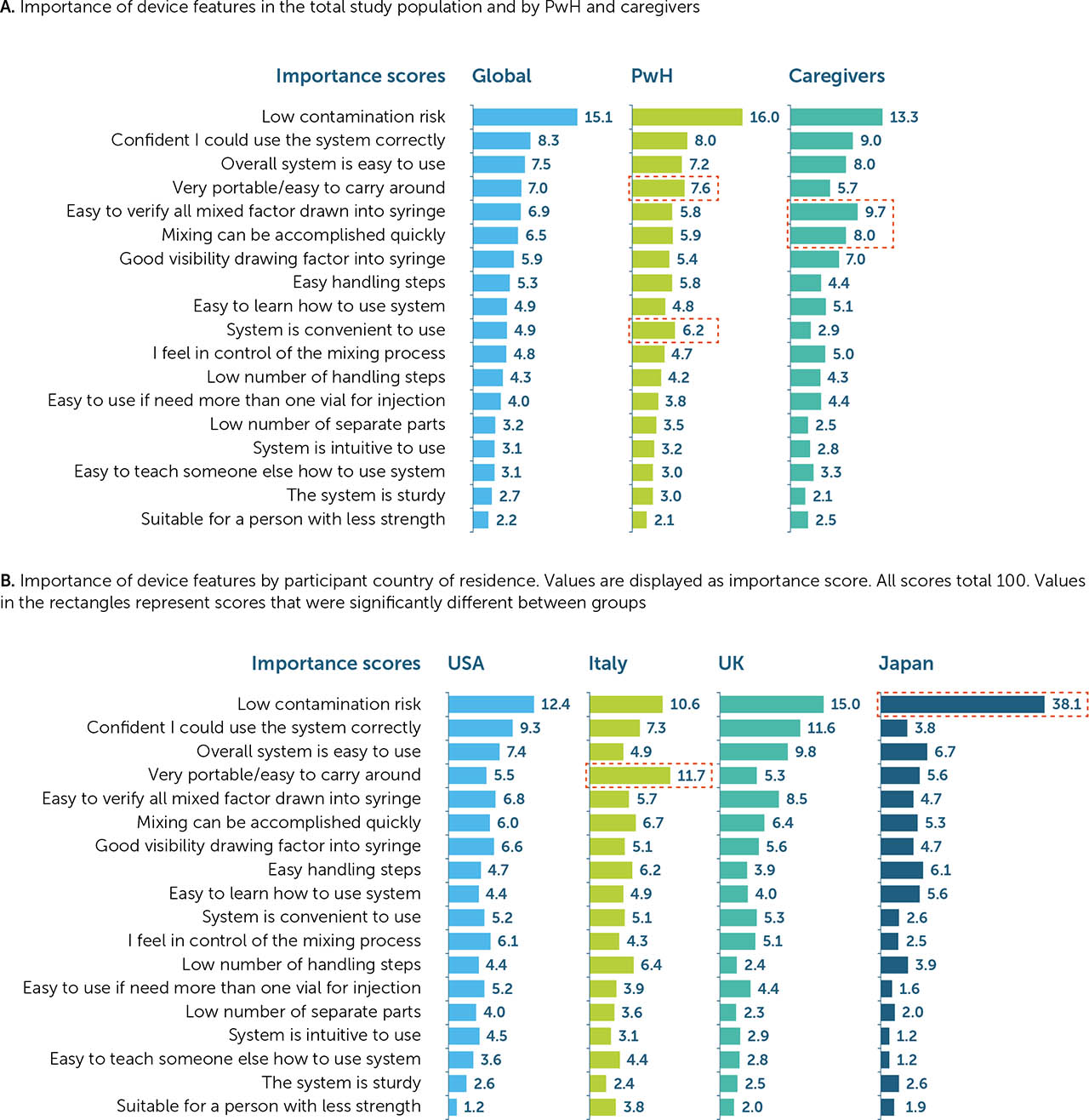

Of the 18 listed device features that were assessed for each reconstitution device, low contamination risk was deemed the most important (importance score: 15.1) overall, scoring twice that of the next most important feature for a reconstitution device. The second most important feature was confidence in using the system correctly (8.3), followed by overall ease of use (7.5). Suitability for a person with limited strength was deemed the least important feature overall (2.2; Figure 2a).

When categorised by demographics (PwH or caregiver), PwH appeared to place more importance on device convenience, rating portability (7.6 vs. 5.7 for PwH and caregivers, respectively), and ease of use (6.2 vs. 2.9) highest. Conversely, caregivers were more focused on device function, rating verifying all factor is drawn up (5.8 vs. 9.7 for PwH and caregivers, respectively) and speed of mixing (5.9 vs. 8.0; Figure 2a) highest. Although low contamination risk was deemed the most important feature among all respondents (both PwH and caregivers) of all ages in the USA and the UK (12.4 and 15.0, respectively), it appeared to be of paramount importance in Japan, where respondents ranked this feature higher than in other countries (38.1). In Italy, however, device portability was deemed the most important feature (11.7), closely followed by low contamination risk (10.6; Figure 2b).

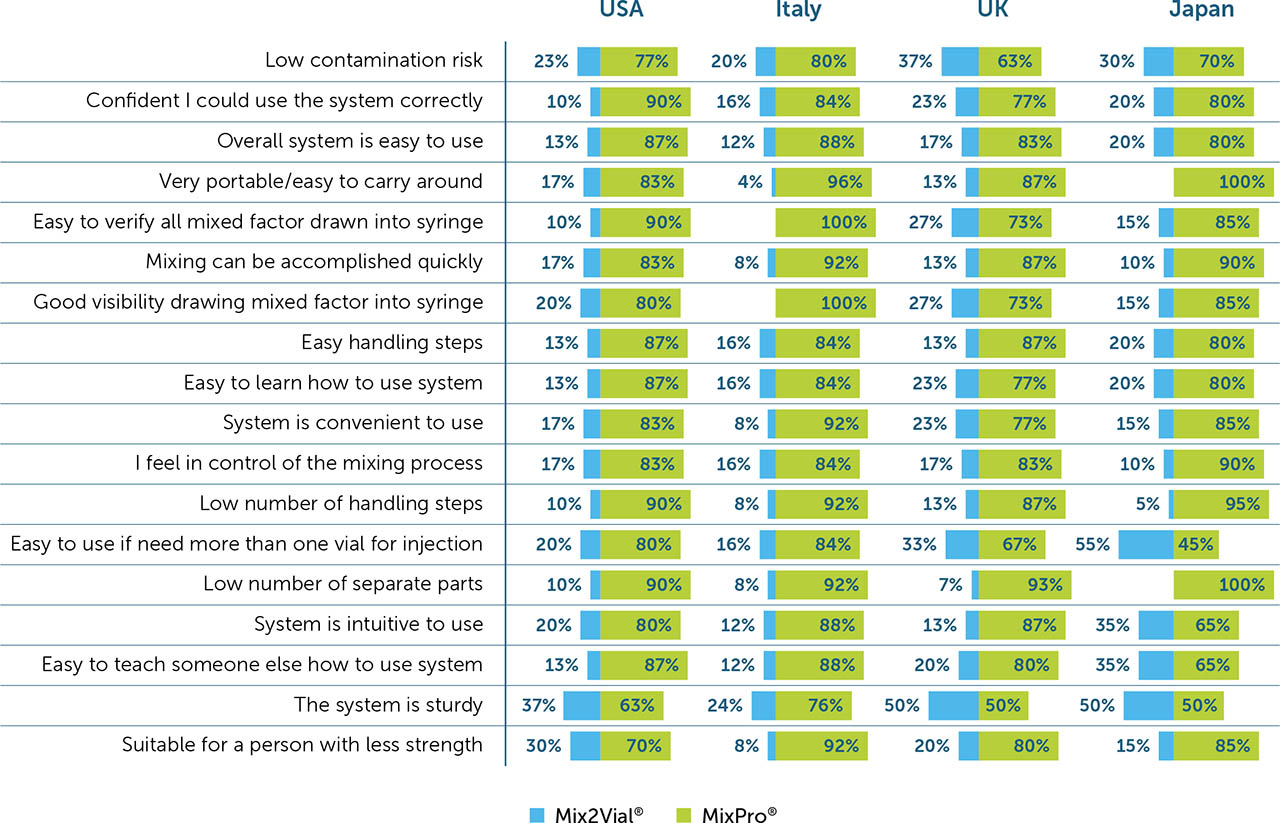

Individual performance rating of benefit features

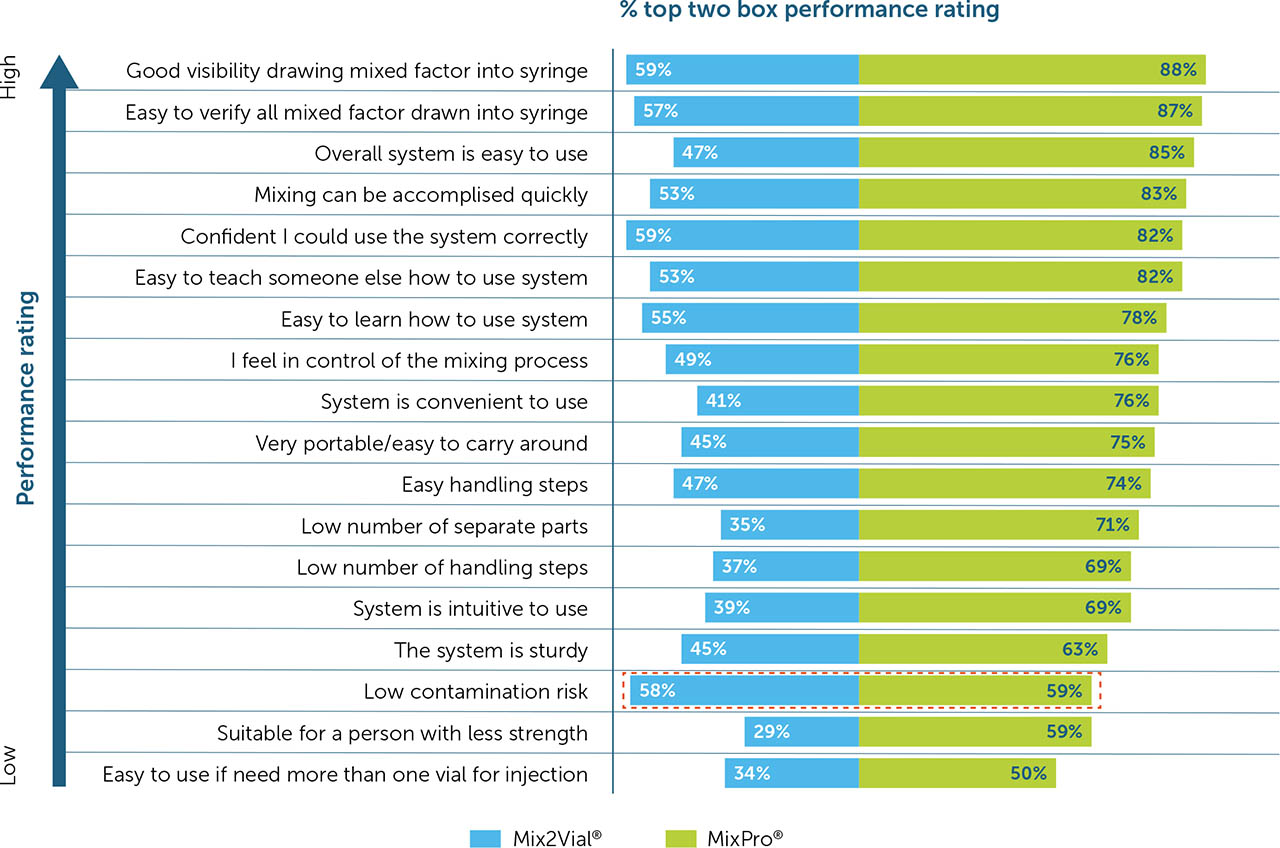

Overall, MixPro® was rated higher than Mix2Vial® for 17 of the 18 benefit features. Low contamination risk was the only feature rated equally for both MixPro® and Mix2Vial® (59% vs. 58% top 2 box rating, respectively). MixPro® was rated most highly on good visibility of product (88%), ease of verifying all factor has been drawn up (87%), and overall ease of use (85%; Figure 3). For Mix2Vial®, good visibility of product and confidence in using the system correctly were the features in which it performed best (59% for both), although still rating lower than MixPro®.

Figure 3

Independent device rating on listed features

Overall device ratings for all listed device features. Devices were rated independently on all features. Values in the rectangle represent comparisons in which MixPro® did not rate significantly higher than Mix2Vial®.

PwH rated MixPro® higher than caregivers did on almost all features, with the exception of low contamination risk (56% vs. 65% for PwH and caregivers, respectively) and ease of verifying all factor has been drawn up (86% vs. 88% for PwH and caregivers, respectively). With Mix2Vial®, PwH also rated the device higher than caregivers on 13/18 features, with the exceptions relating to ease of use, ability to draw up product, and control over mixing steps.

When assessed by country, the USA and the UK generally rated MixPro® higher than Mix2Vial® compared with Japan and Italy.

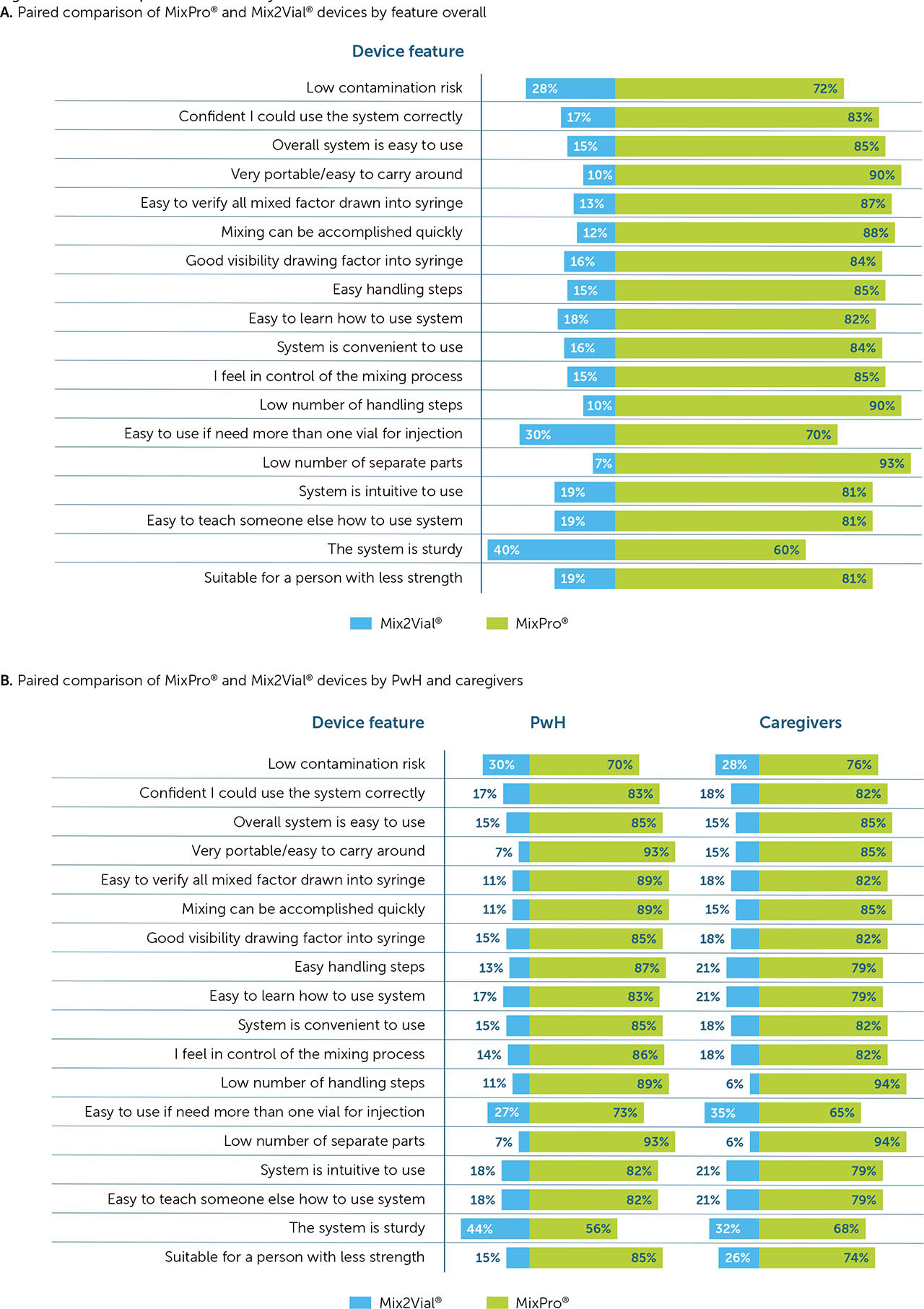

Paired comparison of devices by feature

When participants were asked to choose which device performed better for each of the listed features, MixPro® was selected by ≥60% of participants for each of the 18 features (Figure 4a). Similarly, both PwH and caregivers selected MixPro® as the best performer for all features (Figure 4b).

Regarding country-level evaluations, MixPro® outperformed Mix2Vial® across all features in the USA and Italy. In the UK, MixPro® was selected as the best performer for all the listed features with the exception of the system is sturdy, where the two devices’ preference was split 50/50; this split was also seen in Japan. Further, the only listed feature for which Mix2Vial® outperformed MixPro® in Japan was easy to use if need more than one vial for injection, for which 55% of participants selected Mix2Vial® as the best performer (Supplementary Figure 3).

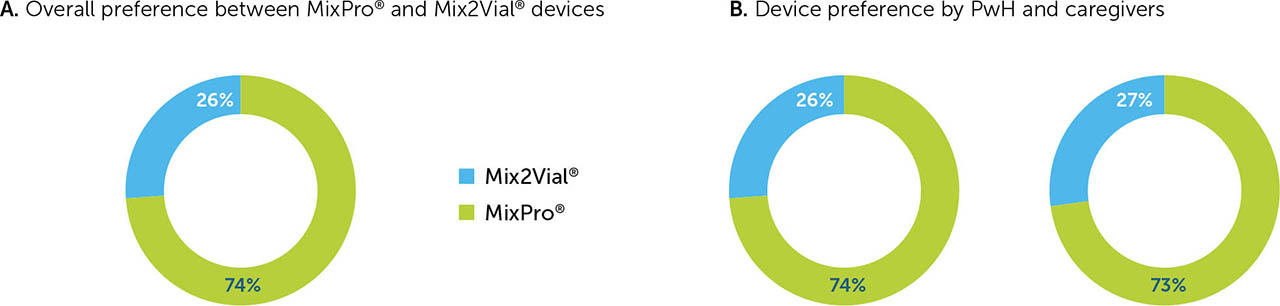

Overall device preference

When asked to select which of the two devices they preferred overall, 74% of participants chose MixPro® over Mix2Vial® (Figure 5a), stating reasons such as MixPro®'s small, compact design; speed and ease of use; and good visibility when drawing up the mixed factor into the syringe. MixPro® was the preferred device for caregivers (73%) and PwH of all ages (74%), across all countries (Figure 5b), with the highest degree of preference being in Italy (78%) and the USA (77%).

Although MixPro® was the preferred device by PwH and caregivers in all countries, in the USA and the UK, PwH had a higher degree of preference for MixPro® compared with caregivers (78% vs. 74% in the USA, and 72% vs. 66% in the UK, for PwH and caregivers, respectively); the opposite was true in Italy and Japan (78% vs. 80% in Italy, and 68% vs. 75% in Japan, for PwH and caregivers, respectively).

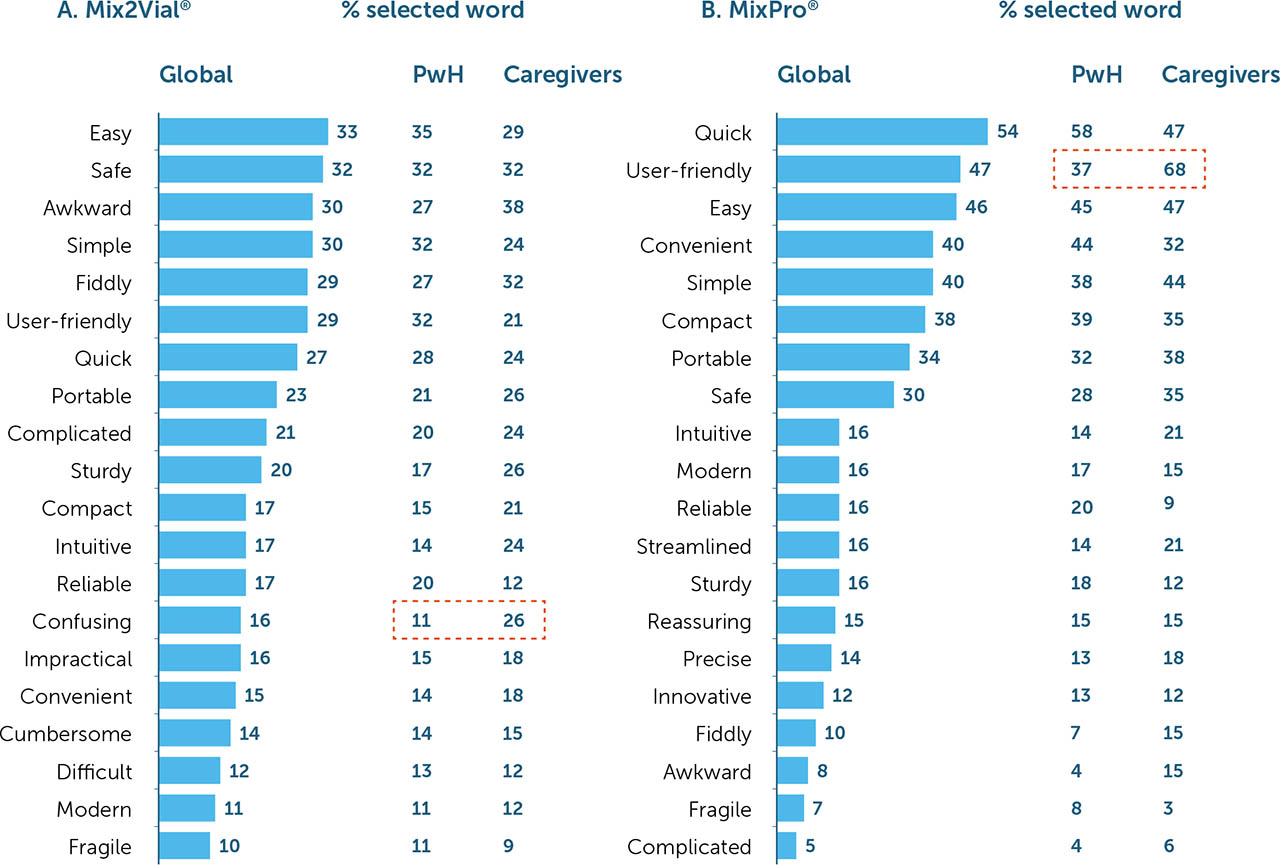

Word association

When participants were asked to select words that they most closely associated with each device, words such as quick (54%), user-friendly (47%), easy (46%), convenient (40%), simple (40%), compact (38%), and portable (34%) were most commonly associated with MixPro® (Figure 6a). For Mix2Vial®, words such as easy (33%), safe (32%), awkward (30%), simple (30%), fiddly (29%), and user-friendly (29%) were most commonly used (Figure 6b). Further, word association for MixPro® was generally positive, with few participants associating this device with ‘negative’ words such as fragile or complicated; word associations for Mix2Vial® were more balanced, with participants using both ‘positive' and ‘negative’ phrases more equally (range 10–33% for Mix2Vial® vs. 5–54% for MixPro®).

All words, with the exception of user-friendly, were associated with MixPro® at a similar frequency for PwH and caregivers. However, caregivers associated the term user-friendly with MixPro® more than PwH (37% vs. 68% for PwH and caregivers, respectively; Figure 6a). For Mix2Vial®, confusing was the only word used more by caregivers than PwH (11% vs. 26% for PwH and caregivers, respectively; Figure 6b).

Impact on life

When participants who preferred MixPro® were asked what impact the device would have on their life, unaided responses included saving time, ease of portability, and general confidence in using the system. Participant responses regarding MixPro® included such remarks as “That slight chance of mix-up with product Mix2Vial® is concerning, no chances with MixPro®, I'll use whatever product reduces that chances of mix error” (Caregiver, US) and “Nice, easy, quick, better for holidays, less packing, less to explain to customs, assume small package, more inclined to take to work so better for emergency situations” (PwH, UK). Only 7% of participants indicated that MixPro® would have no impact on their life.

The overall commentary was limited for Mix2Vial® due to its lower preference overall, with only nine responses. Of those nine, five suggested the device would not have any impact on their life, primarily as it is similar to existing reconstitution devices they are using. Participant remarks on Mix2Vial® included “It is similar to the device I am using, and feel no difficulty” (PwH, Japan) and “Similar to what I am using now but not any better so not much difference” (Caregiver, UK).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis, PwH and caregivers of PwH were asked to provide feedback on two drug reconstitution devices: MixPro® and Mix2Vial®. The proportion of people with haemophilia A was similar to that of the global haemophilia population (86% vs. 82%, respectively), and almost all were administering replacement therapy prophylactically [1].

MixPro® was determined to be the preferred reconstitution device over Mix2Vial® by PwH and their caregivers, regardless of age or country of residence. In line with previous studies, MixPro® was perceived to perform well overall, with participants rating it superior to Mix2Vial® in almost all listed features [3,16]. Speed and ease of use emerged as a common theme for MixPro® throughout these studies, making adherence to recommended self-management practices more feasible [2].

By conducting interviews and asking participants to complete a number of short ranking, rating, and word association tasks, we were able to identify unmet needs of existing drug reconstitution systems, assess the relative importance of key device features, understand the benefits and drawbacks of the MixPro® and Mix2Vial® devices, and determine overall device preference. Based on these interviews, the largest unmet needs for reconstitution devices centre around the speed of reconstitution and the complexity of the device design (i.e. too many parts, too many steps, and limited portability).

When asked to rank the importance of system features, low contamination risk was considered to be the most important feature across all age groups, regardless of whether participants were PwH or caregivers. This is supported by previous studies and World Federation of Hemophilia guidelines, in which risk management is considered a key component of self-management [2,3,16]. In this analysis, the only exception was in Italy, where portability was rated the most important feature, with low contamination risk ranking a close second.

When rated on performance, both MixPro® and Mix2Vial® devices were rated equally for low contamination risk, and this was the only feature where MixPro® was not rated superior to Mix2Vial®. Similarly, when asked to select which device performed best, participants chose MixPro® for all listed features, with the only exceptions relating to sturdiness and ease of use where Mix2Vial® was rated equal or superior to MixPro® in certain countries.

Almost three quarters of participants preferred MixPro® to Mix2Vial® overall, and this trend was seen across PwH and caregivers of all ages in all countries. The preference for MixPro® was also evident in the terms used to best describe each device. MixPro® was most often associated with positive phrases such as quick, user-friendly, and easy, while Mix2Vial® was associated with both positive and negative phrases more evenly such as easy, safe, and awkward. These responses also align with the general unmet needs identified for reconstitution devices and highlight how devices with fewer parts and fewer steps in the reconstitution process are preferred by users.

The most common benefits of MixPro® stated by participants were its compact design with fewer parts, making the reconstitution process convenient; and that it is generally easy to use, meaning less chance of error. This was also reflected by the devices’ impact on life, where saving time and device portability were identified as having the largest impact. With Mix2Vial®, the device benefits were more related to familiarity of the design, speed of reconstitution, and ease of mixing/loading into the syringe. This aligns with participants suggesting that the Mix2Vial® would have no real impact on their life due to the similarity with other devices being used.

These results support previous findings that MixPro® provides an improved tool for drug reconstitution, with key benefits over more traditional, multi-vial systems [3,16].

Limitations

Due to the nature of this comparative, semi-qualitative study, there are some limitations. First, as this study did not exclude participants with prior experience of using either MixPro® or Mix2Vial®, or stratify participants based on level of experience with these devices, potential variations in between groups may have skewed the data. Although participants were permitted to have previously used the devices, they may have been more familiar with one or other, or have never used either device, which may have affected their view. This could also be reflected in their reported unmet needs, as participant responses are likely to vary significantly depending on which type of device they currently use. As these data were not considered in this analysis, we cannot fully interpret the responses. The same may also be true of participant age, given that adolescents tend to assess devices differently to adults, possibly skewing the results.

Second, the study design included both qualitative and quantitative data collection. Qualitative data are innately subjective and open to interpretation, and it is possible that errors or bias were introduced when analysing these data (specifically on unmet needs and impact on life). Additionally, as data were gathered via face to-face interviews, it is possible that some degree of interview bias was introduced. However, the order of features and answers in most tasks were rotated, and interviews were conducted at multiple sites by different interviewers to help eliminate the possibility of bias.

Another limitation is that the paired comparison for device features involved a forced choice, meaning that participants had to choose only one device and could not indicate if they believed the devices performed equally well. This type of questioning could skew results in a particular direction and may not reflect the actual preference.

Finally, although recruitment took place over a number of weeks, the total number of participants in this analysis was small. This limited the type of statistical analyses that could be performed at the segment level and, therefore, precludes any conclusive statements for specific segment analyses (e.g. a caregiver in Italy).

CONCLUSION

Prophylactic replacement therapy remains the recommended treatment for PwH. Although drug reconstitution devices have revolutionised the management of haemophilia and allowed for treatment to be administered at home, the complexity and time-consuming nature of the reconstitution process remains a burden to both PwH and their caregivers.

In agreement with previous publications, participants in this study viewed the MixPro® device favourably, citing its simplicity, compact size, and portability as key benefits. Factors including age, country of residence, and whether participants were PwH or caregivers all affected the relative importance of device features. However, participants consistently rated the pre-filled syringe device, MixPro®, as superior to the more conventional Mix2Vial®, in almost all categories and reported it as the preferred device overall. These data provide further evidence that the speed, convenience, and simplicity of a drug reconstitution device are of paramount importance to PwH and their caregivers and should be considered when making recommendations on replacement therapy for PwH.