A rare case presentation from Upper Assam, India, emphasises the importance of inhibitor screening in people with haemophilia who fail to respond to adequate treatment

© Shutterstock

Haemophilia is an X-linked inherited bleeding disorder, with coagulopathy caused by a deficiency or absence of clotting factor VIII (FVIII) in haemophilia A or IX (FIX) in haemophilia B [1]. It affects all ethnic groups and has a prevalence per 100,000 males of 17.1 cases for all severities of haemophilia A, 6.0 cases for severe haemophilia A, 3.8 cases for all severities of haemophilia B, and 1.1 cases for severe haemophilia B [2]. Clinical manifestations are typically the result of recurrent bleeding episodes, primarily in the musculoskeletal system (more than 80% of haemorrhages). Bleeding into joints and muscles may occur spontaneously and early in life when the disease is severe (i.e. when plasma FVIII or FIX activity is <1% of normal) [3]. Common sites of bleeding include the articular joints and muscles such as the iliopsoas and quadriceps [4]. Bleeding in more unusual sites, including interspinal bleeds, scrotal bleeds and urogenital haemorrhage, has also been reported [5]; haemothorax, or bleeding into the chest cavity, occurs in fewer than 1% of cases [6]. Bleeding in these atypical locations not only becomes difficult to manage but can be severely disabling for the patient. Accurate diagnosis and prompt management is therefore essential.

The standard treatment in haemophilia A is exogenous administration of plasma-derived or recombinant FVIII, which can be used during bleeding episodes or prophylactically. However, there is a risk that the immune system may recognise the exogenous FVIII as a foreign protein and develop neutralising allo-antibodies against it, known as inhibitors, rendering the factor replacement therapy ineffective [7]. Emicizumab (Hemlibra; Roche), which is a recombinant, humanised, bispecific monoclonal antibody, has been shown to be an effective prophylactic treatment for people with haemophilia A and inhibitors [8,9]. Overall reported inhibitor prevalence is 5–7% in haemophilia A; when limited to patients with severe disease the prevalence is higher, at 12–13% [10]. A study of inhibitor development in people with haemophilia in India shows an overall prevalence of around 6%, but this varies and is almost 21% in some parts of the country [11]. Large deletions involving multiple domains of FVIII are associated with the highest proportion of inhibitor formation [12]. The presence of inhibitors should be suspected in any person with haemophilia who fails to respond to adequate treatment with FVIII replacement therapy.

Here, we present a case of extra pleural haematoma, a rarely reported bleeding site, in a person with severe haemophilia A who was subsequently diagnosed with inhibitors.

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old male with severe haemophilia A presented to the emergency department at Assam Medical College and Hospital, Dibrugarh, India, in the month of December 2020 with complaints of diffuse swelling over the left back region for five days. This was associated with a dull aching pain that was exacerbated by activity and had impacted range of motion. There was no history of cough, breathing difficulty, fever or loss in weight and no history of trauma.

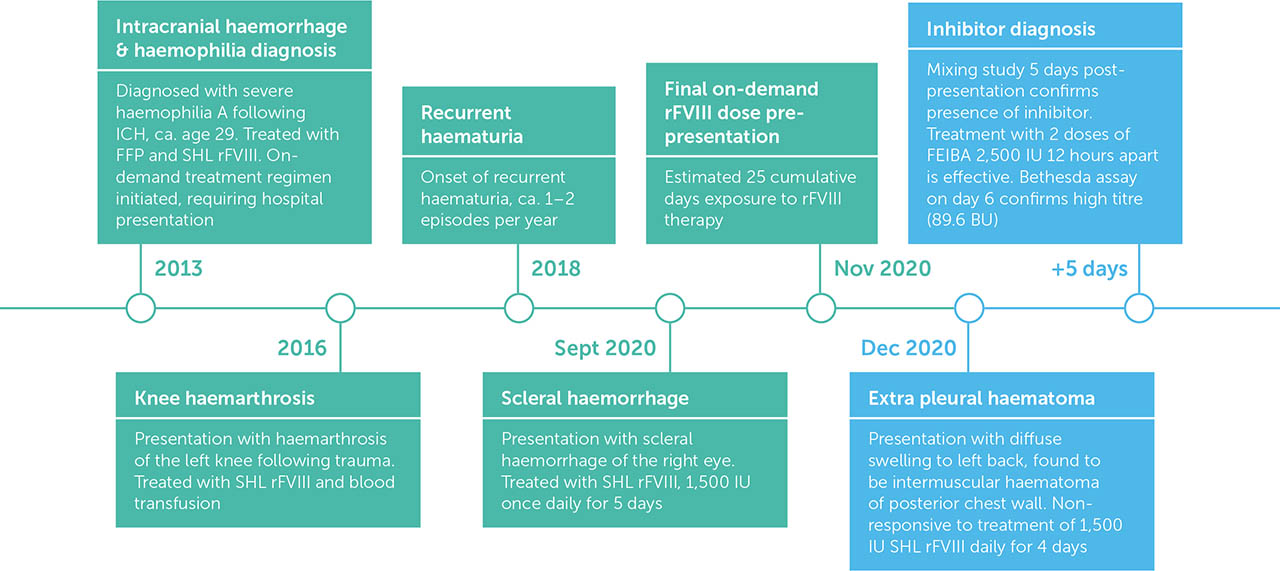

The patient was diagnosed with severe haemophilia A in adulthood following admission to Gauhati Medical College and Hospital, Assam, in 2013 with intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), which was spontaneous in nature. He was treated with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and received recombinant FVIII (rFVIII) concentrates for the first time. He was discharged after seven days and subsequently started on an on-demand treatment regimen with standard half-life (SHL) rFVIII. He is the first child born to a non-consanguineous marriage. His maternal grandfather had similar bleeding diathesis (verbal report). During childhood, he experienced tooth socket bleeding and prolonged bleeding following minor injury, but his diagnosis was delayed due to lack of awareness and proper access to medical facilities. Three years after diagnosis he presented with left knee joint haemarthrosis following trauma, which was treated with rFVIII and a blood transfusion. In 2018 he started to experience recurrent episodes of haematuria, 1–2 episodes per year. Three months before the presentation reported here, he had developed a scleral haemorrhage of the right eye requiring treatment with FVIII concentrate, for which he was administered 1,500 IU of SHL rFVIII once daily for five days. Prior to admission he had received around 25 cumulative days of exposure to FVIII therapy.

Locomotor examination revealed swelling with tenderness in the left scapular region extending posteriorly to back (Figure 1). A thorax CT scan on the day of admission confirmed the clinical findings. A haematoma measuring 5cm (AP) × 6.2cm (TR) × 18.22cm (CC) was noted in the intermuscular plane of the left posterior chest wall, between the serratus anterior and intercostal muscles (Figure 2). Laboratory tests on day 1 showed Hb 9.8 gm/dl (reference range 13–17 gm/dL), PCV 30.8% (reference range 45–54%), and APTT 94.5 sec (reference range 26.5–35.3 sec). The patient was admitted to hospital and treated initially (on the day of presentation) with SHL rFVIII 1,500 IU (desired level 60 IU/dL; patient body weight 50kg) intravenously, with the same dose given on days 2 and 3. The Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery (CTVS) Department was consulted regularly in case of an increase in bleeding and the need for surgical intervention. Based on a clinical suspicion that the patient was not responding to factor replacement therapy, and his history of recurrent bleeding episodes over several years that had required intense exposure to exogenous FVIII, he was screened for inhibitors using a mixing study. After a positive inhibitor screening on day 5, he was treated with the activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC) FEIBA (FVIII inhibitor bypassing activity; Baxter AG), two doses of 2,500 IU intravenously, 12 hours apart. On day 6, a classic Bethesda assay confirmed high titre inhibitors (89.6 BU; inhibitor positive if >0.6 BU). CTVS advised continuation of therapy with bypassing agents and further intervention was eschewed due to the risk of further haemorrhage. By day 7, the patient's pain had improved and the swelling had reduced, following two doses of FEIBA and intravenous tramadol.

The patient was discharged on day 8 following improvement in clinical symptoms and no bleeding, with improvement in Hb (10 gm/dl) and PCV (32.5%). After discharge, he was followed up in the hospital's haemophilia outpatient clinic and CTVS outpatient department after two weeks (Figure 3), and thereafter every two months. His symptoms completely resolved within three weeks. Physiotherapy was started in order to restore the range of motion, muscle strength, and function. He was advised to take FEIBA to treat any other form of bleeding that developed. Fortunately, at the time of his last follow-up in October 2021 he had not experienced any further bleeding episodes.

DISCUSSION

We report on a patient with haemophilia A who was diagnosed with an FVIII inhibitor following presentation with an extra pleural haematoma of the left posterior chest and was successfully treated with bypassing agents (FEIBA). Extra pleural haematoma is extremely rare and we are not aware of any case reports in the literature so far.

Inhibitor development in patients with haemophilia A is a well-documented complication of factor replacement therapy and is more common in patients with severe disease [7]. Our patient, who had severe haemophilia A, had not been treated with FVIII replacement until adulthood and was not treated prophylactically, had a history of stroke (ICH) as well as haemarthrosis of the left knee following trauma (Figure 4). The patient was not diagnosed with haemophilia until he presented with ICH in adulthood, and it is possible that the treatment of these episodes may have triggered inhibitor formation. When compared to on-demand treatment, receiving FVIII replacement as prophylaxis has been associated with a 60% lower risk of inhibitor development [13]. Our patient's on-demand treatment regimen may also have been a predisposing factor to developing inhibitors.

Treatment of bleeding in patients with inhibitors is based on the titre of inhibitor. A low-titre and low-responding inhibitor (5BU) responds to higher FVIII doses, whereas patients with high-titre/high-responding inhibitors must be treated with bypassing agents. Bypass treatment includes aPCC (FEIBA) and recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa; NovoSeven, Novo Nordisk A/S). In the case of a major bleed, the dose of FEIBA is 40–50 IU/kg body weight, which can be repeated every 12 hours; the dose of rFVIIa is 90 ug/kg body weight, which can be repeated every 2–3 hours until haemostasis is achieved [14]. In our case, FEIBA was successful after two doses. It was also important to start physiotherapy to restore the range of motion, muscle strength, and function.

Despite overall improvements in access to factor concentrates and the provision of comprehensive care, access to bypassing agents in India remains problematic [15,16]. At our hospital, we are fortunate to have both FEIBA and NovoSeven in supply from the National Health Mission, Assam. The definitive treatment to eradicate inhibitors in haemophilia A with inhibitors is immune tolerance induction (ITI) therapy [14,17], where increasing doses of factor concentrate are administered over time with the aim of tolerising the immune system so it stops producing antibodies. While ITI is recommended “if practically feasible” in India [15], its high cost also means it is not routinely provided. Prophylaxis with emicizumab, a novel agent that mimics the activity of FVIII, has been shown to be an effective treatment in people with haemophilia A and inhibitors [8,9,17], including in a study of children with haemophilia A and inhibitors treated at a clinic in Delhi [16]. In India, emicizumab was launched by Roche under the brand name Hemlibra in 2019. It will soon be available to start as prophylaxis for patients with inhibitors under the programme National Health Mission, Assam.

CONCLUSION

Treatment for people with haemophilia in India is improving, but there is still a risk of potentially life-threatening complications. Inhibitors that develop later in life in severe haemophilia can be associated with bleeding in unusual sites. The case reported here is a rare presentation of haemophilia A with inhibitors presenting with left extra pleural hematoma. Short-term management with FEIBA has been very satisfactory, however the possibility of recurrence remains unknown. It is essential that physicians are aware of signs that indicate the potential development of inhibitors. The presence of inhibitors should be suspected in any person with haemophilia who fails to respond to adequate treatment, particularly when previously responsive to it.