With appropriate training, physiotherapists can perform and interpret point-of-care ultrasound scans for the assessment of acute haemarthrosis to a level comparable to an experienced sonographer

© Shutterstock

Haemophilia is a haematological condition with orthopaedic manifestations. People with haemophilia (PwH) are prone to several complications. Haemarthrosis is the most frequent complication, accounting for 70–80% of all bleeding episodes [1]. Although any joint may be affected, hinge joints, particularly the ankles, knees and elbows, are the most commonly involved [1]. Blood within the joint space has detrimental effects on all joint structures and leads to the development of haemophilic arthropathy [2,3]. A single haemarthrosis is capable of causing the same long-term arthropathy as seen in recurrent haemorrhages [4,5]. Time between the initiation of joint bleeding symptoms and treatment with factor replacement therapy is crucial; however, some haemarthroses may present ambiguously. On initial presentation it may be difficult to assess if acute joint pain is due to a joint bleed or underlying arthropathy [6]. Recent evidence suggests that clinical examination alone is not sensitive enough to detect small amounts of blood within a joint [4,6,7]. Therefore, each bleeding event requires early and complete bleed assessment and management to ensure the best possible outcomes for PwH.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for the detection of haemarthrosis, however it is expensive, often inaccessible, and may require sedation of children to ensure that the images are not compromised by patient movement [8]. Computed tomography (CT) is another sensitive method; however, the benefits of CT may not outweigh the downside of ionising radiation [8,9]. Ultrasound is time-efficient, nonionising, and relatively inexpensive [8,10,11,12]. Ultrasound can detect complex fluid suggestive of blood within the joints of patients who are clinically asymptomatic, leading to the recommendation that ultrasound be used in combination with the clinical exam to inform treatment decisions following haemarthrosis [7]. However, clinical integration of ultrasound is limited by timely access to sonographers/radiologists with knowledge and experience in haemophilia. Further, treatment of haemarthrosis is time-sensitive, and same-day diagnostic imaging appointments are not always feasible. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a modality that has the potential to address many of these challenges. POCUS is performed by a health care professional (HCP) at the bedside or in the ambulatory clinic, in combination with the clinical examination to identify the presence or absence of a specific clinical finding [13]. POCUS should be utilised when time saving for diagnosis or treatment is critical to patient care [13]. However, POCUS is a highly user-dependent modality, and there is a risk of misdiagnosis if it is used to aid clinical decision-making by inexperienced or untrained HCPs [14].

Proficiency with the clinical examination and an understanding of the role of POCUS are important competencies for physiotherapists [15]. POCUS has been described within physiotherapy practice in orthopaedics or sport injuries to detect atrophy, tendon, ligament or muscle injury, in rheumatology to assist clinical decisions, and as a potential tool for physiotherapists working in critical care [16,17,18,19,20,21]. It is important that physiotherapists who are using POCUS have confidence in their interpretation and findings, as this could impact the credibility of the profession, patient safety, support from regulatory colleges and licensing bodies, and collaboration with medical colleagues. A survey of orthopaedic surgeons and radiologists in the Netherlands reported no additional value of physiotherapist-performed POCUS in primary care [22]. This is a single study that assessed the subjective opinions of survey respondents; perceived disadvantages of physiotherapist-performed POCUS were false-positive or false-negative results, lack of experience, inadequate training, and the inability to correlate the reported findings on POCUS with other forms of imaging [22]. Even though this study reported a low survey response rate and a potential for response bias, the lack of trust radiologists and orthopaedic surgeons reported for physiotherapist knowledge and performance of POCUS in primary care should be addressed through future studies [22]. Rathi and colleagues investigated the inter-rater reliability of glenohumeral joint translation using POCUS [23]. Although high intra-rater reliability (physiotherapist: ICC 0.86–0.98, expert sonographer: 0.85–0.96) was found, it was moderate to good for posterior measurements (ICC 0.50–0.75) and poor to moderate for anterior measurements (ICC 0.31–0.53). These results suggest that to improve inter-rater reliability with an expert sonographer, the physiotherapist may benefit from additional or a different form of training [23]. Similar findings were reported by Thoomes-de Graaf and colleagues, who found a kappa coefficient of 0.36 between physiotherapists and radiologists on the use of diagnostic ultrasound in patients with shoulder pain across four diagnostic categories [24]. Although the level of agreement was low, this study reported that physiotherapists with more experience and training had a higher level of agreement with the radiologist than novice physiotherapists [24].

Training appears to be an important contributor to inter-rater reliability of physiotherapist-performed POCUS. Mayer and colleagues found excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC range 0.76–0.97) between a physiotherapist, physiotherapy students, and an expert physician sonographer following eight hours of structured formal training as a group and a one-hour private practical training session with the expert sonographer [25]. An inter-examiner agreement study of physiotherapists in the Netherlands found an acceptable level of overall agreement (61.7–93.6%) and specific positive agreement (43.9–91.4%) for detecting rotator cuff tears and other pathology [26]. The physiotherapists in this study had obtained certification on basic musculoskeletal ultrasound skills and completed a six-hour training programme specific to the study protocol with an expert in musculoskeletal sonography [26].

Physiotherapists in haemophilia treatment centres (HTCs) have extensive knowledge of anatomy, pathophysiology, and functional implications of a bleeding disorder on the musculoskeletal system. A global survey of HTCs found that the majority (70%) of POCUS scans were completed by physiotherapists [27]. In this study, an interdisciplinary panel of haematologists/oncologists, radiologists, and physiotherapists reported that physiotherapists are appropriate users for the acquisition and interpretation of POCUS scans in HTCs [27]. While several researchers have studied diagnostic ultrasound and the correlation with disease activity and haemophilic arthropathy, inter-professional agreement and an evaluation of image quality for physiotherapist-performed POCUS in PwH with acute haemarthrosis has not been investigated [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Inter-professional agreement and evaluation of image quality are important measures of competency and acceptable use of POCUS. Image quality provides evidence to support the diagnosis of a bleed and decreases the chance of artifact incorrectly demonstrating pathology. Given the role of physiotherapists within HTCs in Canada, and the emergence of POCUS, the present pilot study aims to add novel research to this discussion.

Objectives:

To determine the level of agreement between physiotherapist and sonographer-performed POCUS to assess for the presence or absence of blood in acute haemarthrosis in people with haemophilia A and B.

To compare the quality of the ultrasound images obtained by the physiotherapist to those obtained by the sonographer.

METHODS

Participants

A convenience sample of PwH with a suspected acute hemarthrosis of the elbow, knee, or ankle were recruited from a single HTC in Canada. The physiotherapist (KS) who performed the POCUS scan is a member of the Canadian Physiotherapists in Hemophilia Care, successfully completed the McMaster University Mohawk College POCUS Training Program for Acute Hemarthrosis and Synovitis, and has 17 years of experience in haemophilia care. The training programme includes 12 hours of online didactic modules and a two-day, 12-hour practical training module with instructor-led hands-on practice [34]. The didactic modules include summative assessments, and the practical component includes an assessment of competency using a simulated performance environment. The assessments were created to model the Sonography National Competency Profile developed by Sonography Canada and the Sonography Canada Clinical Skills Assessment Tool for this specific application of POCUS [34]. The sonographer (LF) who performed the ultrasound scan is a senior sonographer in the diagnostic imaging department at a large tertiary care hospital and has over 30 years of clinical experience in sonography. A single radiologist (NS) with 12 years of experience in ultrasound imaging and 10 years’ experience in paediatric imaging, provided oversight to the study and reviewed all POCUS scans and case report forms.

Study procedures

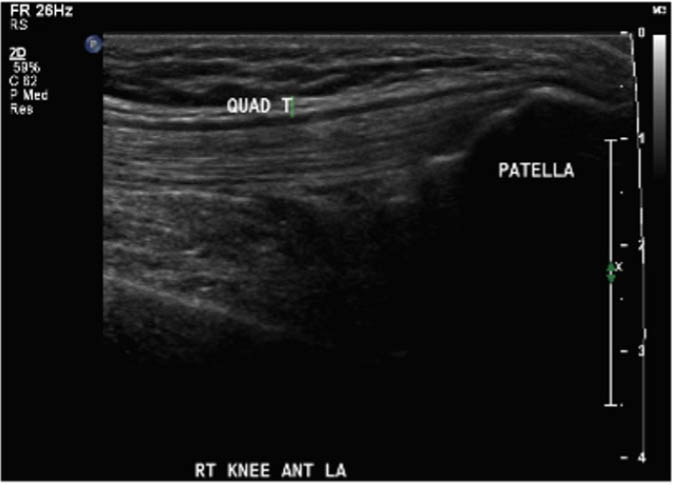

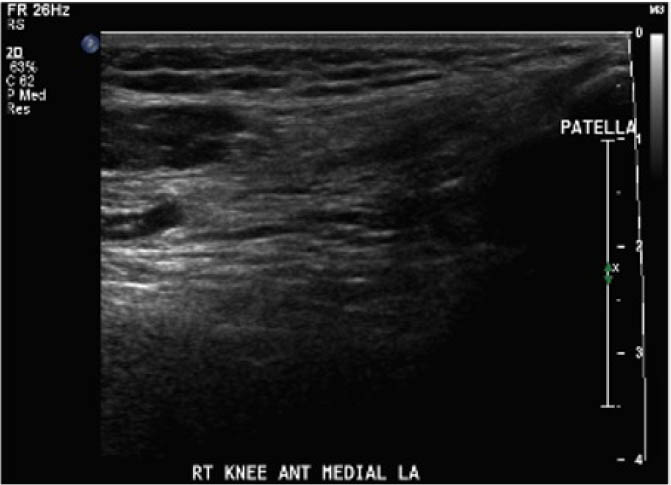

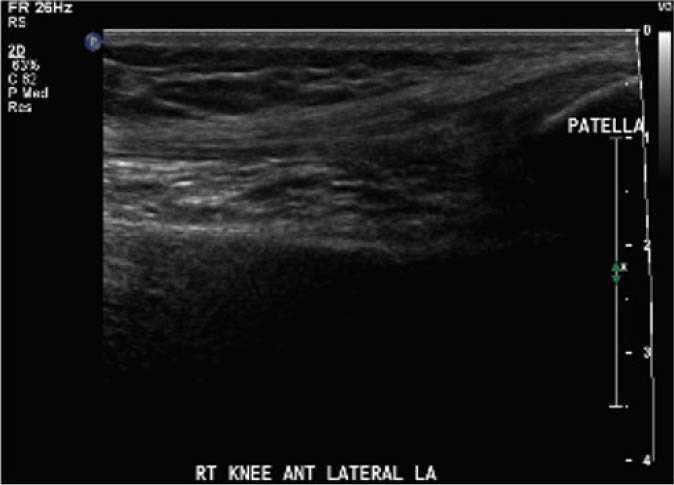

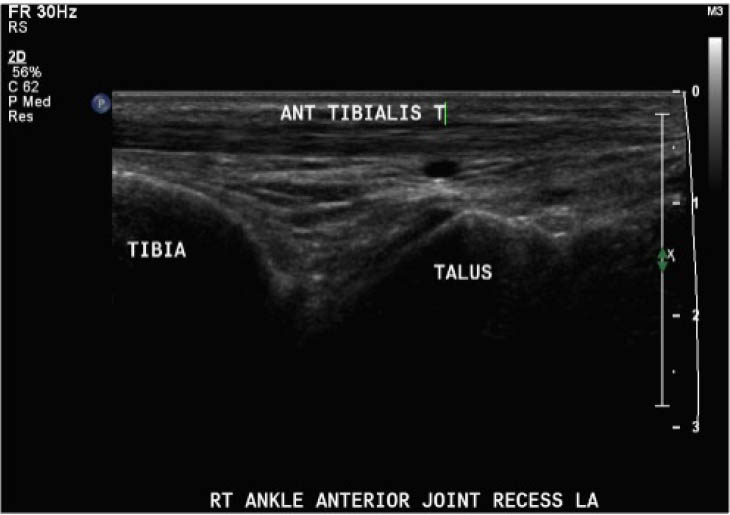

The study procedure consisted of a POCUS performed by a physiotherapist and a sonographer. The POCUS scanning procedure is presented in Appendix 1. The POCUS scans were performed in the haemophilia ambulatory clinic at patient presentation, one-week follow up, and two-week follow-up. The order of assessment was based on clinician availability. The sonographer was allowed to add additional images to the imaging protocol given their area of expertise, but the physiotherapist was instructed to acquire the images according to the scanning procedure. Ambiguous results were referred to the diagnostic imaging department for further formal investigation. Both the physiotherapist and the sonographer were blinded to each other's findings and to the results of previous scans. Methods of blinding included the use of a private clinic room and each clinician performing their assessment and documentation independently. Case report forms were placed in a sealed envelope. POCUS images were saved on the hard drive of the POCUS machine (GE Logiq) using an anonymous participant identification number.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients (age >1 year of age) with haemophilia A or B, with an acute haemarthrosis involving the elbow, knee, or ankle who presented to the clinic within five days of symptom onset were eligible to participate. Participants were excluded if there was an open wound over the scanning area, if an ultrasound scan of the haemarthrosis had already been completed, or if they were not able to read and understand English.

Outcome assessment

Outcomes were assessed at presentation, one-week follow-up, and two-week follow up, resulting in a three-week study period. For the primary objective, the outcome of interest was the binary decision on the presence or absence of blood within the joint. As the technique and protocol in this study was specific to haemophilia, the criteria used to distinguish blood from effusion on ultrasound was blood presents as a complex fluid collection with mixed echogenicity and displaceable speckles on real time compression and effusion presents as simple anechoic fluid with the absence of echoes [35]. In the context of haemophilia with no symptoms suggestive of infection, complex effusions with mixed echogenicity can be assumed to represent haemarthrosis based on previous studies that have documented the accuracy of this approach using joint aspiration [35]. The physiotherapist completed the scanning protocol and interpreted the findings to make the binary assessment. Since interpreting ultrasound falls outside the scope of the sonographer, the sonographer provided an impression on the presence or absence of blood on the case report form. The radiologist read the sonographer images and provided a final diagnosis. The radiologist also reviewed the images of the physiotherapist performed ultrasound. To compare the level of agreement, the radiologist's final diagnosis was compared to the physiotherapist's interpretation. Both the physiotherapist and the sonographer recorded inconclusive ultrasound findings as absence of blood within the joint.

For the secondary objective, criteria used to evaluate image quality were appropriate pre-sets, depth, field of view, focus, gains/time gain compensation, colour and/or power Doppler, with suitable landmarks and annotation. Image quality was evaluated by the radiologist post hoc and rated as optimal, acceptable, or sub-optimal. Optimal was defined as good image quality with optimal ultrasound settings and correct annotation/documentation. Acceptable was defined as good image quality, with one image setting that should have been better optimized or a minor error in annotation/documentation that did not impact the interpretation of the POCUS scan. Sub-optimal was defined as poor image quality with more than one image setting not sufficiently optimised or an error in annotation/documentation that impacted the radiologists’ interpretation of the POCUS scan.

Statistical analysis

For the primary objective, the prevalence of positive findings was calculated. The inter-rater agreement of the binary assessment of the presence and absence of blood within the joint was assessed with the kappa coefficient and 95% confidence intervals for the total sample and interpreted according to the categories by Landis and Koch [36]. As this is a pilot study, we did not set an a priori threshold for agreement. Observed agreement, specific positive agreement and specific negative agreement were also calculated to provide the results in a clinically relevant format [37]. For the secondary objective, the quality of the images was independently rated by the radiologist. Descriptive statistics including counts and percentages of optimal, acceptable, and sub-optimal for the physiotherapist and the sonographer performed POCUS scans were reported.

RESULTS

Thirteen PwH met the inclusion criteria and were recruited into the study. Two of the POCUS scans involved elbows (15.4%), five (38.5%) ankles, and six (46.2%) knees. The median age of participants was nine years (interquartile range: five years).

Level of agreement on the presence or absence of blood within the joint

As presented in Table 1, the kappa coefficient was k=0.80 (95% CI, 0.59–1.00). The prevalence of positive findings was 70.8%, observed agreement was 91.7%, the specific positive agreement was 94.1%, and the specific negative agreement was 85.7%. The sonographer was absent and unable to complete three POCUS scans, these scans were excluded from the level of agreement analysis.

Quality of ultrasound images

Post hoc analysis of the quality of the ultrasound images is shown in Table 2. The physiotherapist-performed POCUS scans demonstrated that 84.6% of the images were rated by the radiologist as optimal, 15.4% were rated as acceptable, and none were rated as sub-optimal. For the sonographer-performed POCUS scans, 88.9% of the images were rated as optimal, 11.1% were rated as acceptable, and none of the scans were rated as sub-optimal.

Table 2

Quality of ultrasound images

| QUALITY OF ULTRASOUND IMAGES | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OPTIMAL | ACCEPTABLE | SUB-OPTIMAL | |

| Physiotherapist | 84.6% | 15.4% | 0% |

| Sonographer | 88.9% | 11.1% | 0% |

DISCUSSION

Although pilot in design, this study adds to the emerging literature supporting the quality of physiotherapist-performed POCUS. The level of agreement between physiotherapist and sonographer is encouraging, suggesting that a trained physiotherapist is able to acquire and interpret POCUS scans of acute haemarthrosis in patients with haemophilia A and B at the same level of expertise as an experienced sonographer [36]. The specific positive agreement was greater than the specific negative agreement indicating better agreement when confirming the presence rather than the absence of blood within the joint. Clinically, these results indicate that if the physiotherapist performed and interpreted the POCUS scan as positive for presence of blood within the joint, the probability that the sonographer and radiologist would also confirm haemarthrosis is 94.1%. Encouraging results were also found for the absence of blood within the joint with the probability of absence of blood at 85.7%. While agreement was less for the absence of blood, the results were still high. Clinically, this supports physiotherapist consultation with radiology to determine whether further imaging is required if the POCUS scan indicates a lack of blood in the joint but other indicators such as patient symptomatology, mechanism of injury, inhibitor status, trough level, and underlying joint health, are all highly suggestive of haemarthrosis. The quality of the images obtained by the physiotherapist were optimal and comparable to the sonographer. This indicates that the trained physiotherapist was able to produce images that support the diagnosis on the presence or absence of a joint bleed with a low likelihood of imaging artifact incorrectly demonstrating or missing pathology.

In clinical practice, POCUS images are seldom stored for future review or comparison [38]. This process has been questioned as it limits the possibility of performing quality assurance audits and does not acknowledge the importance of reviewing serial scans to assess for the evolution/resolution of pathology [38]. To be consistent with this process and to maintain the independence of POCUS scans, the current study blinded the physiotherapist and the sonographer to the images and findings from previous scans. However, given the evolution of blood on ultrasound, the potential for underlying joint arthropathy in PwH, and the role of normal physiologic fluid in synovial joints, it may be important for the POCUS operator to have access to previous POCUS scans. Being able to access previous images can facilitate analysis of the clinical evolution of pathology and physiologic fluid, which may have implications on the level of agreement between the trained physiotherapist and sonographer as there may be variations in agreement at different stages of recovery. Also, recording previous images may decrease health care costs. If the POCUS scans are done with similar standards as diagnostic imaging, accessing stored images may avoid the need for repeat scans if clinical questions arise that may require consultation with radiology. These considerations may have implications for education and clinical practice and will be important areas for future study.

The current study had a number of strengths. The physiotherapist was trained to a set standard for this specific application of POCUS by an accredited academic institution. Both the physiotherapist and the sonographer were blinded and were provided with a standardised scanning protocol, with the order of assessment randomised based on clinician availability. Both the physiotherapist and the sonographer used the same ultrasound machine and after each POCUS scan the machine was returned to the main screen to maintain blinding and the independence of scans. All 13 participants recruited into the study attended all study visits. Lastly, the study procedures were consistent with the traditional pathway in diagnostic imaging. The study was designed in this manner to ensure that the same quality and standard of care was provided in the clinic setting.

Although this is a pilot study, its main limitations are the small sample size and inclusion of a single physiotherapist and sonographer, both of which may impact generalisability. While the results suggests that a short training programme provided the physiotherapist with an appropriate level of education and training in the performance, acquisition, and interpretation of POCUS scans in PwH, this needs to be replicated with physiotherapists and sonographers with varying levels of training and experience. It would be interesting to compare the competencies of sonographers with no musculoskeletal experience to physiotherapists who have completed POCUS training specific to the musculoskeletal system. Future inter-professional agreement studies should also consider including other members of the haemophilia comprehensive care team, such as physicians/haematologists and nurses, who may be using POCUS in clinical practice. In addition, with the decreasing annualised bleeding rates in PwH [39], a multi-centre trial would be needed to obtain a sufficient number of suspected bleeding episodes for a definitive study.

This study focused on hinge joints of the knee, ankle, and elbow, which account for the majority of haemarthrosis in PwH and are easily accessible with relatively simple POCUS scanning protocols. Future research would need to look at the inter-professional agreement and image quality for more complex joints, such as the ball-and-socket joints (i.e. shoulder and hip). Although haemarthrosis could occur in patients with other musculoskeletal injuries, these results should only be applied to the assessment of haemarthrosis in patients with haemophilia [40,41,42]. The protocol and training received by the physiotherapist in this study was specific to haemophilia and it is important to remember that one of the downsides of POCUS occurs when users extrapolate beyond their protocol and training [13]. Generalising the findings of this study to patients with other conditions should therefore be done with caution. However, this study does demonstrate that within a relatively short period of formal training, including both didactic and practical curricula, physiotherapists can become proficient in POCUS. Given their background knowledge in anatomy and physiology, this study lends support for physiotherapists to be trained to use POCUS with different patient populations and conditions.

CONCLUSION

Optimal image quality and an excellent level of agreement between the physiotherapist and sonographer-performed POCUS for the assessment of acute haemarthrosis in people with haemophilia A and B was observed. This pilot study found that a physiotherapist who received appropriate training in the McMaster University Mohawk College Training Program can perform and interpret POCUS scans for the assessment of acute haemarthrosis to a level that is comparable to an experienced sonographer. Further investigation is warranted.