Women with a bleeding disorder (WBD), whether diagnosed with a symptomatic bleeding disorder or labelled as a carrier, say that excessive bleeding significantly impairs their social and romantic life and their physical activities [1]. However, this has only relatively recently been acknowledged by the healthcare community. Even now, the challenges women face are under-recognised. This is due to the historical lack of scientific research relating to WBD and barriers to timely diagnosis [2,3], the latter also being influenced by cultural obstacles such as stigma and taboo associated with menstruation[4]. In one recent study of WBD, including women labelled as haemophilia carriers, four major themes of concern were identified: uncertainty surrounding diagnosis (including distinguishing between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ bleeding patterns), conceptualisation of experience through family bleeding (considered secondary to an affected male family member), intensity of bleeding symptoms, and impact on identity and daily life [5]. Heavy periods have the biggest impact on daily life of all the challenges facing WBD [1].

The Haemophilia Society in the UK has been promoting awareness about the impact of bleeding disorders on women for several years via the Talking Red campaign [6]. As part of this initiative, the Society surveyed WBD to investigate the impact of heavy periods on their daily lives. The survey predated the UK government's decision to remove VAT from sanitary protection products and the Scottish government's decision to provide free access to sanitary products in public buildings in Scotland.

METHODS

WBD were invited to participate in an online survey during six weeks in January and February 2020. The survey was delivered via the platform Mailchimp (https://mailchimp.com) and promoted to WBD via The Haemophilia Society's social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram). The questionnaire comprised 20 questions about personal data (age, location, diagnosis), symptoms (menstruation, pain), and impact on social life. In particular, information was sought about the practicalities of living with a bleeding disorder by enquiring about duration of bleeding, use of sanitary protection products, and the impact associated with bleeding on clothes and bedding. Incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the analysis.

RESULTS

Demographics

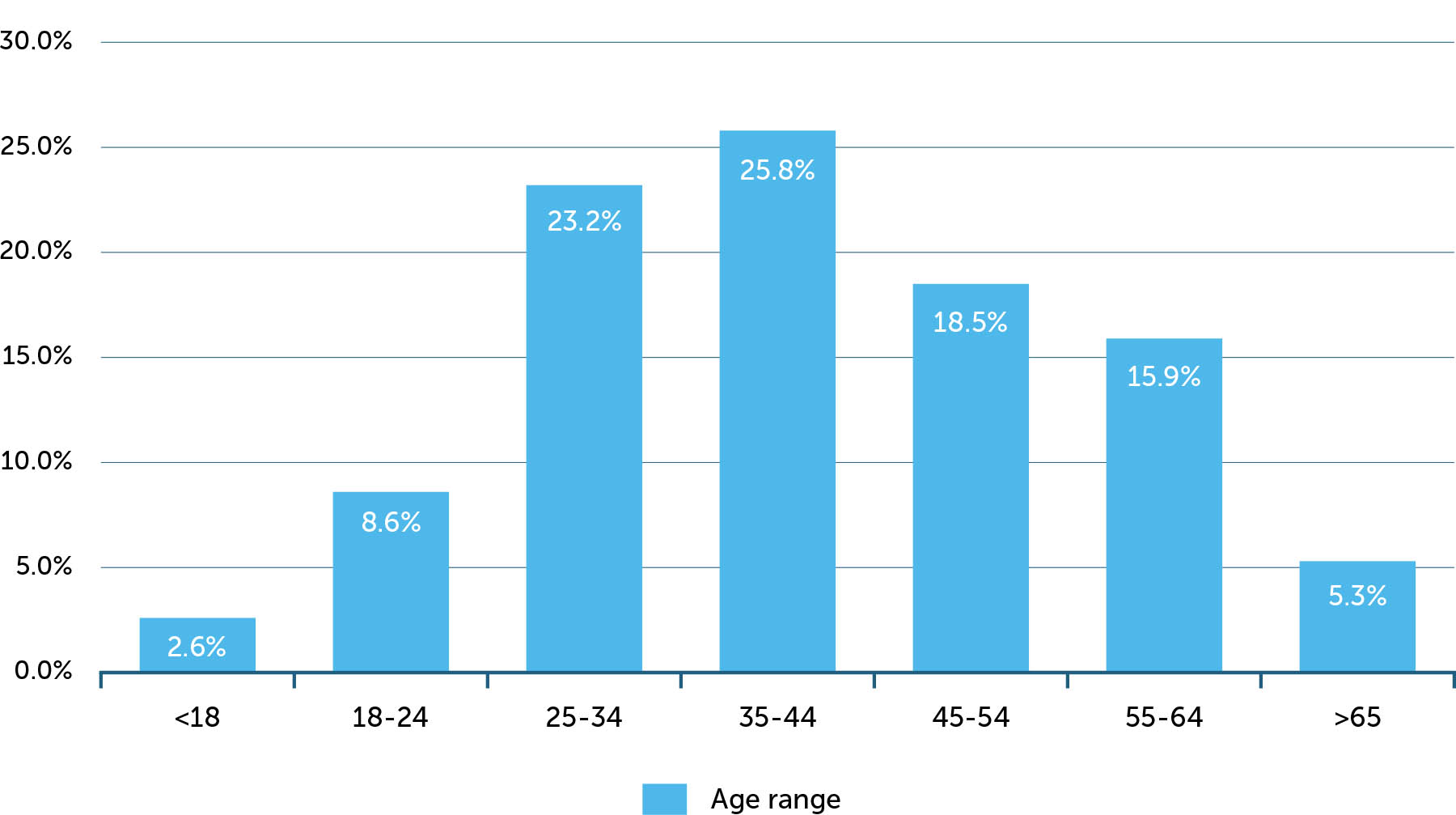

A total of 181 responses were received, of which 151 (83%) were complete questionnaires. Respondents were distributed throughout the UK, with the majority in England (Figure 1). Approximately 58% of respondents were aged 18–45; 90% were aged 18–64 (Figure 2).

Bleeding disorders

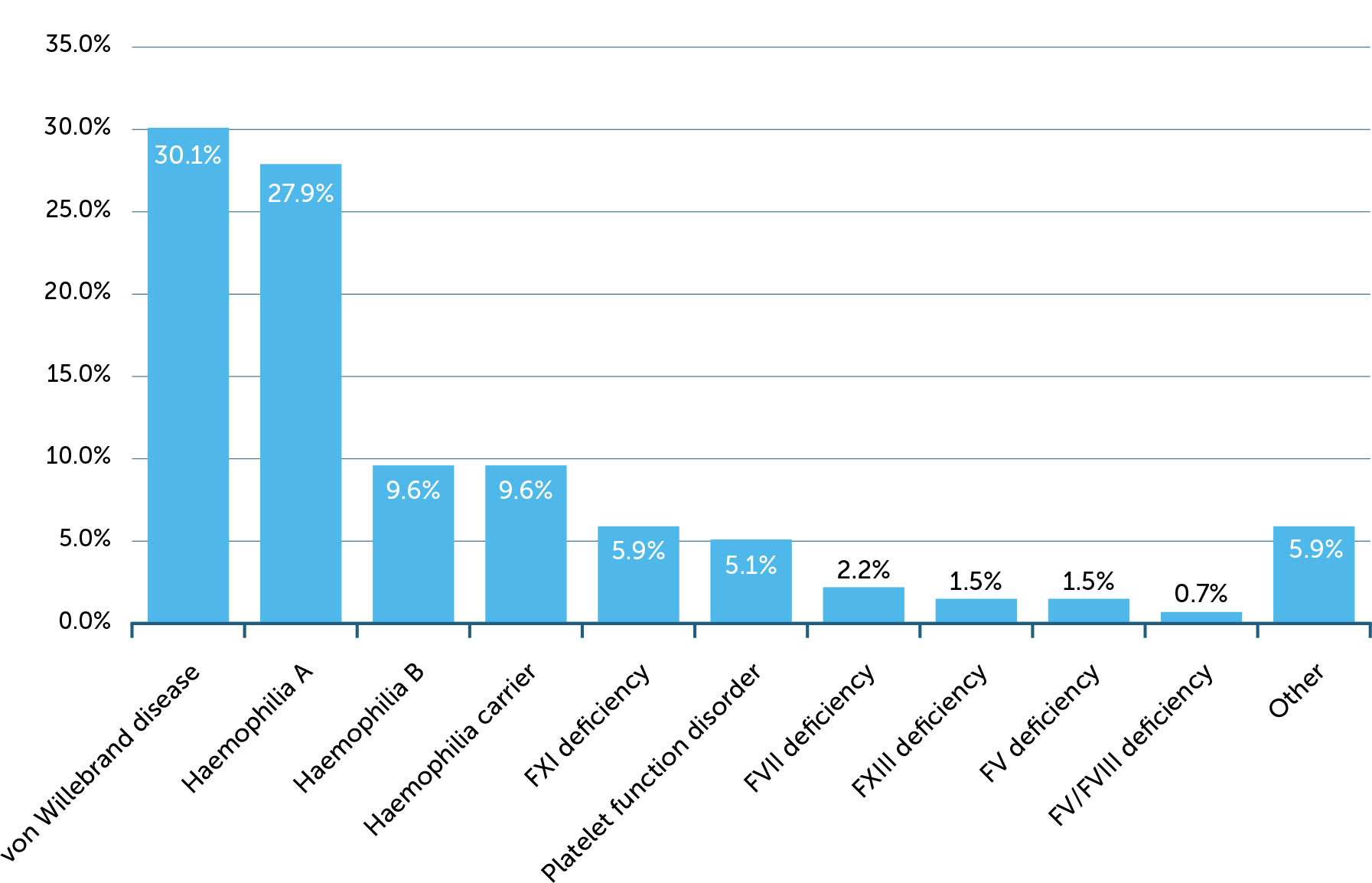

Ninety per cent of respondents (136/151) stated they identified as a person with a bleeding disorder (Figure 3). One respondent reported a diagnosis of activated protein C resistance, a hypercoagulation disorder, but reported heavy periods which may have been due to anticoagulation; this respondent was excluded from the analysis. The majority had von Willebrand disease (VWD) or haemophilia A or B; 13 women stated they were carriers, of whom 11 specified they were carriers of haemophilia A. Specified platelet disorders included storage pool deficiency, Glanzmann's thrombasthenia and immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Three respondents stated they did not know what their bleeding disorder was; two stated it was unclassified or undiagnosed; and two stated menorrhagia.

Of the 15 respondents who did not identify as a person with a bleeding disorder, none reported a diagnosis, but they did report signs and symptoms of heavy menstrual bleeding. These data were therefore analysed separately.

Age at diagnosis was specified by 126 of the 130 women reporting a diagnosis. Median age at diagnosis was 18 (range 0–60). Of the remainder, one was diagnosed in childhood, two as teenagers, and one was unsure.

Signs and symptoms associated with bleeding disorders

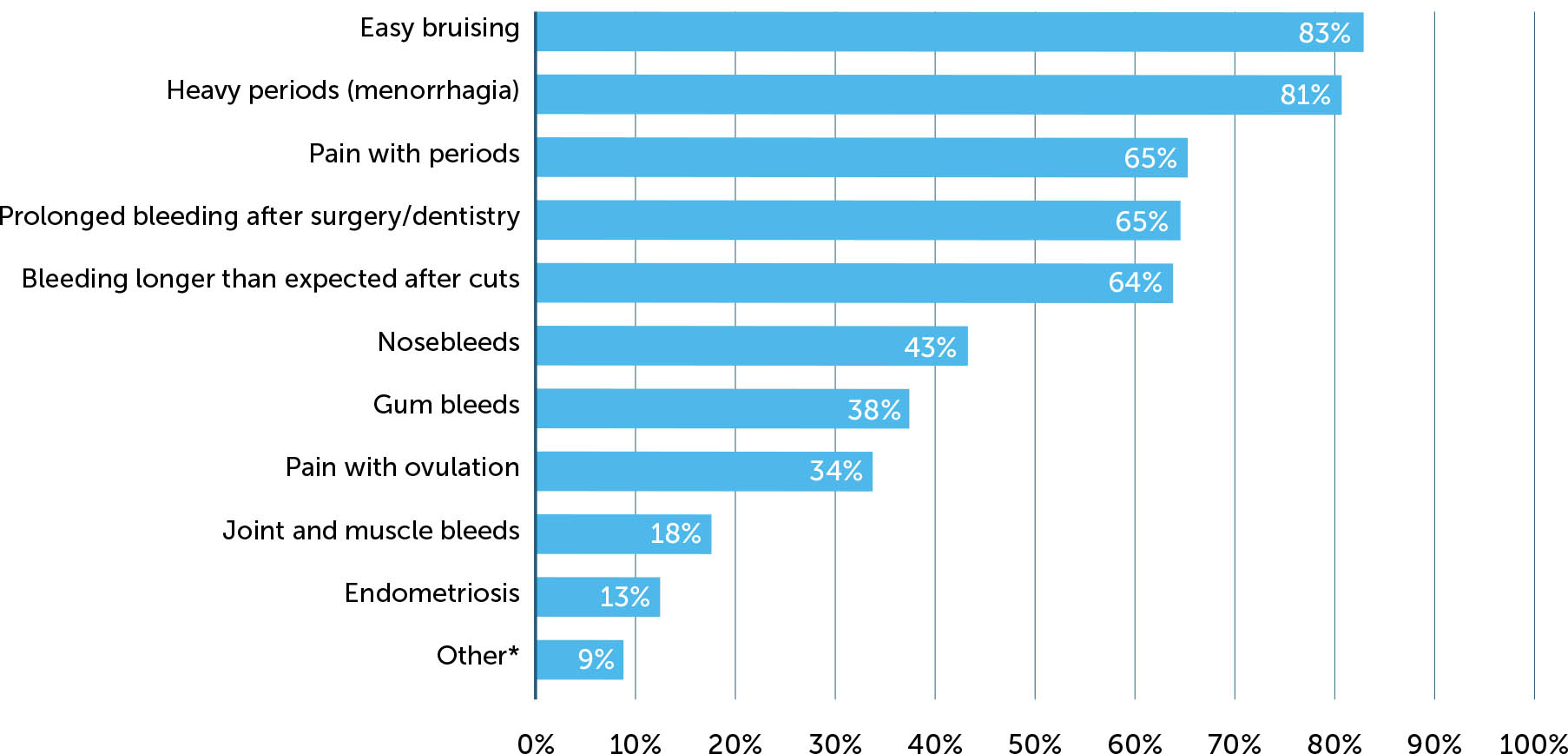

Most respondents reported experiencing easy bruising, heavy periods and prolonged bleeding after cuts, surgery or dental procedures (Figure 4). Pain with periods was reported by approximately two thirds of respondents and with ovulation by about one third. Events that were consistent with spontaneous bleeds were nosebleeds (43%), gum bleeding (38%), and joint and muscle bleeds (18%). ‘Other’ reported events included gastrointestinal bleeding (n=4), subarachnoid haemorrhage (1), prolonged bleeding after childbirth (1), and chronic severe anaemia (1).

Figure 4

Reported signs and symptoms associated with bleeding disorder

*Other symptoms reported by respondents were random soft tissue bleeding after exercise and minor joint bleeding; gastrointestinal bleeds, including due to angiodysplasia; the unpredictable nature of bleeding and pain when bleeding after a knock or injury; gastrointestinal bleeds; easy bruising and long-lasting bruises; prolonged bleeding after childbirth; large clots during period; blood transfusions after surgery; and subarachnoid haemorrhage (spontaneous bleed).

Impact of bleeding disorder on periods

Data on the duration of periods was provided by 121 respondents, of whom 100 provided solely numerical data (i.e. not qualified by text). Interpreting ranges as the maximum duration (i.e. ‘7–10 days’ = 10 days), the median duration of periods was 7 days (range 2–42), and 8% of respondents reported periods lasting ≥15 days. Of the 21 remaining respondents, five reported periods of very variable duration (5–28 days) or irregularity; five reported no or shortened periods following intervention (medication, IUD, ablation); eight reported no longer having periods (e.g. due to menopause); and three stated this question was not applicable.

Information about taking time off work or study due to heavy periods was provided by 121 respondents. Of these, 36% stated they had taken time off, 42% stated they took no time off, and 6.6% did not know. Forty-two women provided information about the duration of time taken off: 19 stated one day, 17 stated 2–3 days, one stated 3 or more days, three stated 4–5 days, one stated 7 days, and one stated 12 days. Six respondents said they carried on working or rearranged work during their period, one of whom stated this was ‘a struggle’; two mentioned ‘suffering’ and reduced productivity. One mentioned occasionally taking time off due to pain. Nine stated they no longer had periods due to surgery or the menopause, they did not work, or the question was not applicable.

Forty-two per cent of respondents stated their bleeding disorder affected their social life (Appendix 1). Three themes can be defined: not going out, going out despite the impact of periods (or ‘not applicable’), and symptoms. Reasons cited for not going out were very heavy bleeding, debilitating symptoms, worry about flooding or staining in public, and access to toilet facilities or sanitary products. Public embarrassment from staining was a frequent theme. Symptoms were sometimes extreme or severe and included pain, tiredness (including feeling drained, lethargy and fatigue), anxiety, weakness, nausea, fainting, and altered mood (lack of motivation, feeling uncomfortable, on edge, paranoid). Respondents who stated they did go out used strategies such as ensuring access to toilet facilities and taking spare clothing to manage bleeding, or rearranging travel and their social life around their periods (e.g. only going out with friends ‘who understand’). Several stated that their periods had no impact on their social life (including due to the use of contraception) or that they did not let it.

The treatments currently used for heavy menstrual bleeding recorded by respondents are listed in Table 1. These treatments may not have been used exclusively to treat period symptoms, or if a treatment is not mentioned it may not have been perceived by the respondent as a treatment for period symptoms. The most frequently cited was tranexamic acid, which was taken by 23 of the 41 respondents with VWD, 18 of the 64 with haemophilia or diagnosed as a haemophilia carrier, and 18 of the remaining respondents.

Table 1

Current treatments for period symptoms (n)

| TREATMENT | NUMBER OF RESPONDENTS |

|---|---|

| Hormone therapies (oral)* | 37 |

|

|

|

| Mirena intrauterine device | 22 |

|

|

|

| Desmopressin | 8 |

|

|

|

| Tranexamic acid | 60 |

|

|

|

| Other | |

| Factor replacement | 4 |

| NSAIDs | 3 |

| Simple analgesics | 2 |

| Other intrauterine device | 1 |

Sanitary protection

The types of sanitary protection recorded by respondents are listed in Table 2. Several respondents reported having to use the largest size of tampon, heavy duty night-time pads and ‘ultra’ towels, several pads at night, and incontinence pants or period pants.

Table 2

Sanitary protection used by respondents (n)

| PRODUCT | NUMBER OF RESPONDENTS | PRICE RANGE FOR PRODUCT* (£ PER UNIT) |

|---|---|---|

| Menstrual cup | 5 | 14–30 |

|

|

||

| Night sanitary towel | 25 | 0.07–0.23 |

|

|

||

| Sanitary towel | 28 | 0.05–0.14 |

|

|

||

| Tampon | 36 | 0.05–0.13 |

|

|

||

| Other | ||

| Combination of two products | 14 | – |

| Combination of three products | 4 | – |

120 respondents provided information about their expenditure on sanitary protection. Most spent £2–£10 per month (39%) or £11–£20 per month (37%). Thirteen women (8.6%) spent £25 or more per month. Of these 13 respondents, one was diagnosed as a haemophilia carrier, six had VWD, two had haemophilia, and one had factor XI deficiency; two stated their diagnosis was menorrhagia and one did not know her diagnosis. Ten reported at least one additional bleeding symptom (e.g. nosebleed, excessive post-surgical bleeding) and 11 said they did not have a social life/leave the house during their period.

Of the 14 respondents who did not report expenditure, 11 were peri- or postmenopausal and three reported one-off spending on a menstrual cup (of five users of such products). Eighteen respondents said they had at some time struggled to pay for sanitary products, nine of whom reported spending £25 or more per month. Twenty-four respondents (20%) stated they had at some time used substitutes for sanitary products (e.g. socks, toilet paper) because they could not afford to buy pads or tampons. Three specified they had used toilet paper or kitchen towel; one stated she had used ‘hand towels, nappies in plastic pants, also just sitting on the loo bleeding’.

Asked ‘What other monthly expenses do you have as a result of your heavy periods (e.g. bedding, clothing, etc.)?’, 82 provided information (listed in Appendix Two), of whom 78 mentioned having to frequently wash or discard bedding and/or clothing, including a mattress in two instances. This was an occasional expense for some respondents but constant or frequent for others. One correspondent stated she had lost her job as a result of excessive bleeding. Three respondents estimated their additional monthly expenditure at £12, £15 and £20.

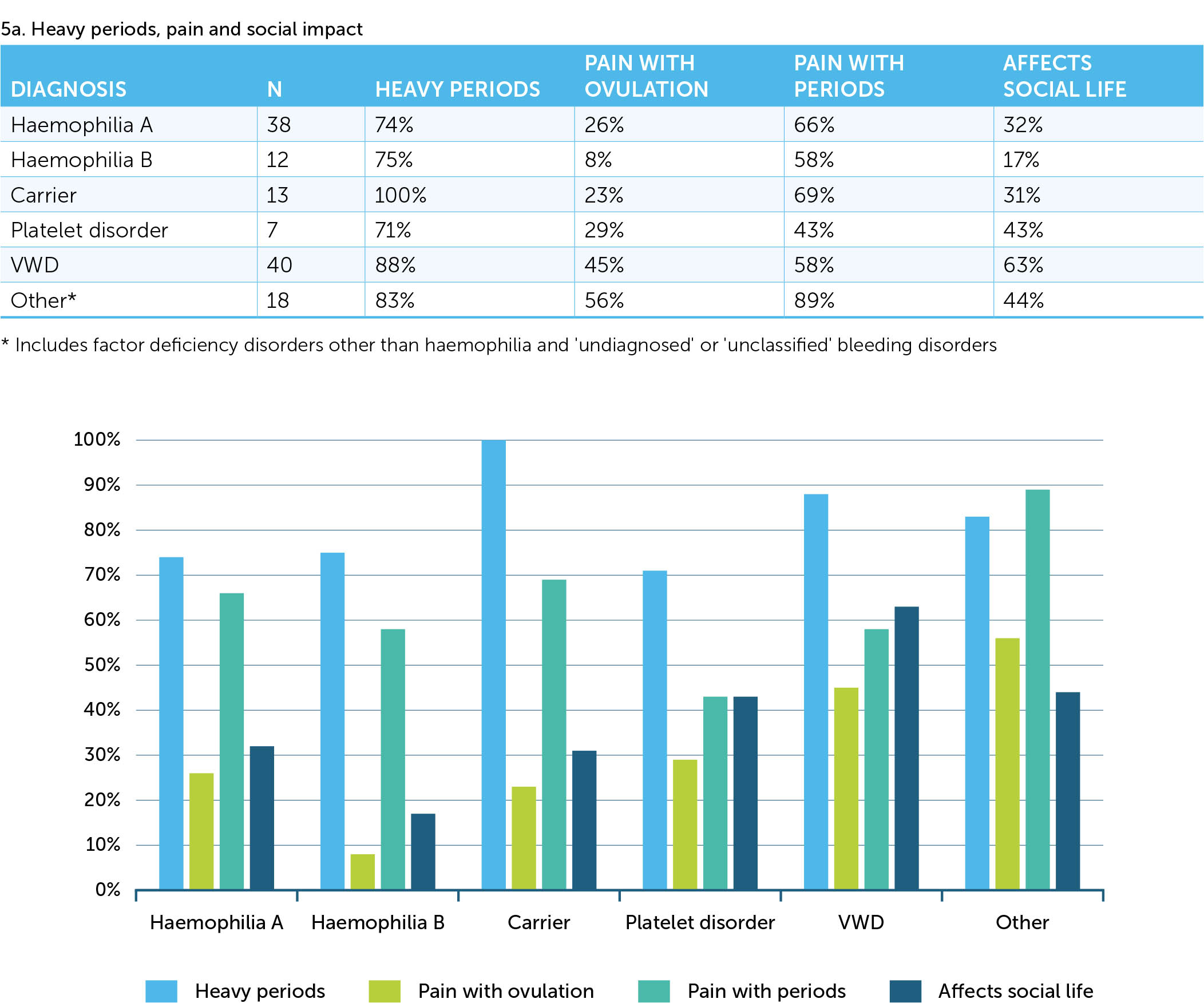

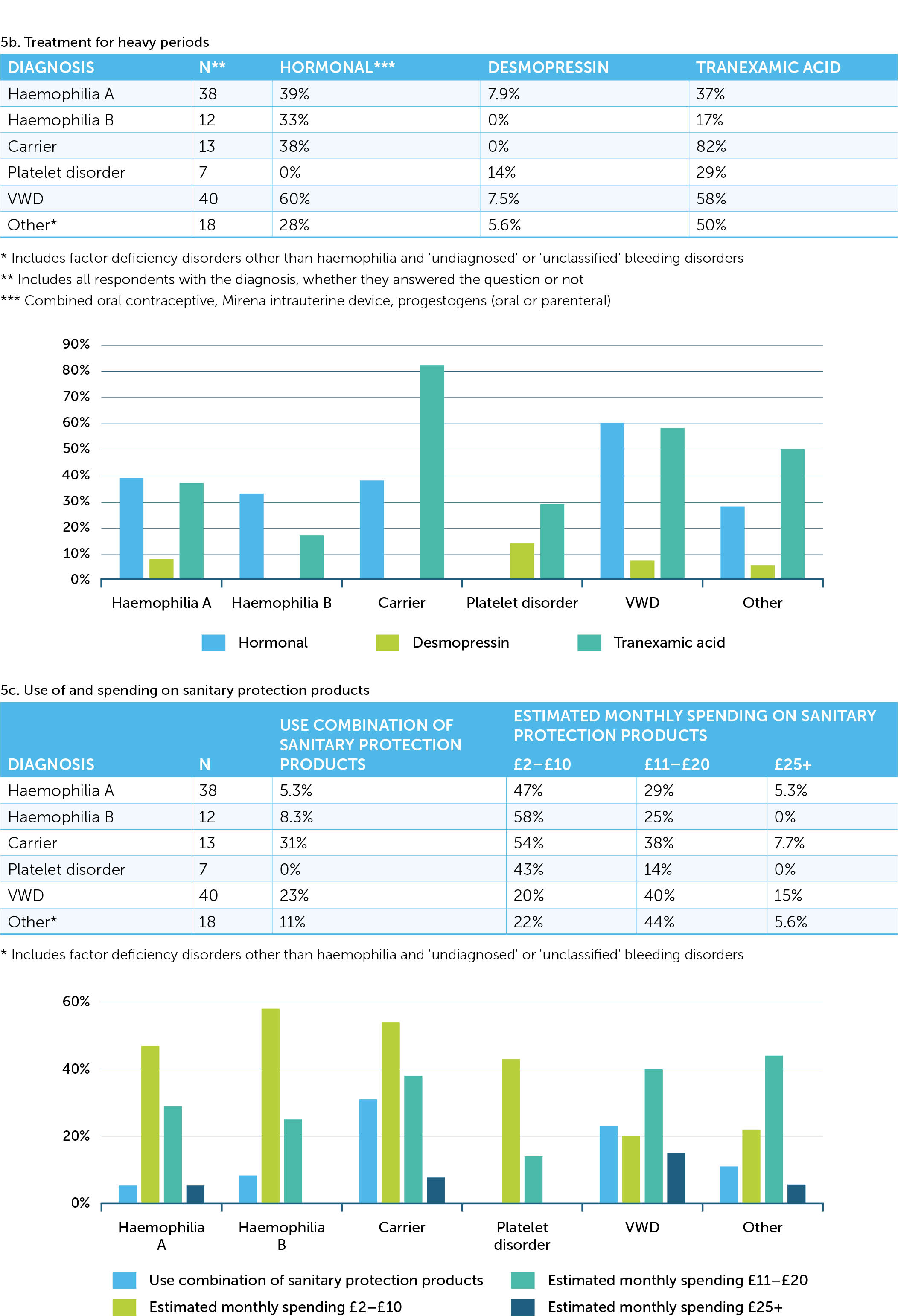

Differences between bleeding disorders

Numbers of respondents with bleeding disorders other than haemophilia A or VWD were small but some trends are evident (Figure 5). The proportion reporting heavy periods was higher for women diagnosed as a carrier than for those with a bleeding disorder, and though similar proportions reported painful periods, a smaller proportion reported an impact on social life. This group also reported a higher prevalence of treatment with tranexamic acid and a comparable prevalence of hormonal medication. Finally, more respondents in this group reported using a combination of sanitary protection products. Compared with respondents with haemophilia A or B, a higher proportion of respondents with VWD reported an impact of periods on social life, hormonal treatment and use of tranexamic acid, use of combinations of sanitary protection products, and a tendency for higher spending on sanitary protection products.

Women who did not identify as a person with a bleeding disorder

Of the 15 women who did not state that they identified as a person with a bleeding disorder, 11 were aged <45 and two were aged ≥55. Two stated they were diagnosed as carriers of haemophilia and a further two probably were: one stated she had given her son his ‘life-threatening bleeding disorder’ and one stated she had four sons with haemophilia. For this subgroup of respondents, the median duration of an ‘average’ period was seven days (range 5–10). Ten respondents stated they never took time off work or studying due to their period, and three stated they did so for between two and five days. The impact of heavy periods on social life was similar to that for the main cohort, with some women severely limited; others were either unaffected or had developed a strategy to allow socialising to continue (Appendix 1). Medication for periods included tranexamic acid (n=7), the combined oral contraceptive (3) and the Mirena coil (3). Nine respondents used solely sanitary towels and five used solely tampons; one used a combination of both. Monthly expenditure on sanitary protection products was £2–£10 for six women, £11–£20 for six women, and ≥£25 for two women. Three women said they had at some time struggled with paying for sanitary protection products, in one case when a student but not currently. Four had substituted other items when they could not afford sanitary protection products (one when a student). All but one of this subgroup stated the additional costs associated with heavy periods included washing and replacing bedding and clothing; the other respondent stated she sometimes doubled up pantyliners.

DISCUSSION

The lives of many women with bleeding disorders are blighted by the consequences of prolonged bleeding. This survey shows that not all women are affected in all respects but the impact on those who do experience heavy bleeding can be profound, such as heavy and painful periods that are difficult to manage and impose severe limitations on social life. Some respondents described being unable to leave home during their period because they could not manage the heavy bleeding. Some feared the social consequences of their bleeding becoming apparent and suffered stigma, anxiety and worry. About 60% of respondents took time off work or studying due to their periods. Conversely, some women continued their social and work lives despite their symptoms – for example, stating they did not let their periods stop them or that they made provision to manage their bleeding. These problems were not specific to any bleeding disorder and were shared by women who had been diagnosed as a carrier.

Up to 40% of the respondents were old enough to be potentially peri- or postmenopausal; this information was not specifically sought in the questionnaire but was inferred or included by nine respondents (i.e. they mentioned menopause or stated ‘not applicable’ when answering the question about period duration). Not surprisingly, they tended to report less impact from heavy bleeding.

The median duration of periods was slightly longer than the norm for the UK. According to information for the public provided by the NHS (https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/periods), periods typically last for between three and eight days, with an average duration of five days. The median duration for respondents was seven days, but 8% reported a duration of 15 days or more and the maximum duration was 42 days. This presumably reflects episodic and very disruptive bleeding. About 16% of respondents reported having to use a combination of two or three sanitary protection products to manage their bleeding, suggesting that the volume of bleeding is very high for a substantial proportion of women. Eighteen respondents reported struggling to pay for their sanitary protection products at some time and several mentioned having to substitute alternatives such as toilet paper as a consequence. The highest level of spending (£25+ per month) accounted for only half of these cases, suggesting that bleeding severity is not a reliable indicator of the hardship associated with heavy periods. Government action to reduce taxation and increase access to sanitary protection is therefore welcome, but for most WBD expenditure also includes the cost of frequent washing and replacement of clothes and bedding, and therefore the economic burden will persist for many women.

Most respondents in this survey had been diagnosed with haemophilia A or VWD, reflecting the higher prevalence of these disorders, but women diagnosed as a haemophilia carrier or with haemophilia B each accounted for about 10% of respondents. This is lower than the proportion of cases registered in the UK National Haemophilia Database which includes 6,243 males and 2,617 females with haemophilia A (31% females) and 1,245 males and 591 females with haemophilia B (32%) [7]. Even these figures are likely to underestimate the prevalence of bleeding disorders in women as many haemophilia treatment centres do not measure levels of factor VIII and factor IX or may not register these women in the database. The prevalence of menorrhagia is estimated at 30% [8], and among women referred for investigation of menorrhagia the prevalence of a bleeding disorder is 17–30% [9, 10, 11]. It has been suggested that for each male with haemophilia there are 2.7–5 potential female carriers, 1.5 actual somatic carriers, and 0.3–1 carriers with factor VIII or factor IX activity below 0.4 IU/mL[12].

It is possible that WBD were more likely to respond to the survey if the impact of their disorder was greater, in which case the results may reflect – albeit indirectly and inaccurately – the level of harm experienced by some women. Further, the distinction between the label of ‘carrier’ and a diagnosis of haemophilia may be blurred. Of the 15 women who did not answer ‘yes’ to the question ‘Do you identify as having a bleeding disorder?’, four stated or inferred they were a haemophilia carrier and reported excessive bleeding. This lack of awareness in some women that carrier status is not a benign diagnosis suggests the need for greater recognition among health care professionals and education of families living with haemophilia.

The most frequently used treatments for excessive bleeding were tranexamic acid and hormonal products; this is consistent with current practice [13]. Four respondents stated that they used factor replacement, of whom three had VWD and one was diagnosed as a haemophilia A carrier. Given the prevalence of heavy, prolonged bleeding and pain among respondents, and the impact on social life, this treatment strategy is clearly not successful, though the data provided in this survey are not sufficient to determine where treatment is failing individual women.

Comparisons between bleeding disorders are limited by small numbers but there is a striking trend for a higher proportion of women diagnosed as a carrier to report heavy bleeding, and to have more prevalent treatment with tranexamic acid and more frequent use of a combination of sanitary protection products. (Paradoxically, they also report a lower social impact.) This highlights the possibility that women diagnosed as carriers have a significant burden of morbidity and management but perhaps receive less support than others who, with a diagnosis of a bleeding disorder, have access to specific treatment. The survey did not request information about investigations carried out to reach a diagnosis. This would have revealed whether factor activity had been measured in those diagnosed as a carrier or if they had been informed of this status solely as part of genetic counselling. Further studies are needed to explore how this gap in management can be bridged, including the wider of use of factor VIII, factor IX and von Willebrand factor measurement in women in families with a bleeding disorder.

Limitations

This survey was conducted over a brief period in the UK and was accessible only to women capable of using online media who were aware of or associated with The Haemophilia Society. The respondents may therefore have greater awareness and/or concern about heavy menstrual bleeding. The absence of randomisation in the recruitment of respondents raises the risk of bias due to self-selection; it is therefore unclear how representative the respondents are of WBD in the UK. The number of respondents was relatively small, and it was not possible to draw definitive conclusions about the characteristics associated with different bleeding disorders. Details of treatment such as factor prophylaxis or on-demand factor replacement, perhaps more likely to be used in women with VWD than haemophilia carriers, were not recorded and these are likely to be an important determinant of the frequency and severity of bleeding symptoms.

CONCLUSION

This study confirms that WBD experience a high prevalence of heavy bleeding and prolonged, painful periods despite using appropriate symptomatic treatment. For some, this has a profound impact on their mental health and limits their social life due to fear of embarrassment and stigma. It also shows that the morbidity experienced by women diagnosed as a carrier is comparable with that described by respondents with a diagnosis of bleeding disorder. This suggests they have inadequate access to care and support because they are clinically unrecognised. Women who are haemophilia carriers are underrepresented in bleeding disorders registries, raising the possibility of a substantial unmet need. Respondents reported that heavy periods were difficult to manage and may require the use of several sanitary protection products combined. Bleeding in women diagnosed as carriers may be worse than reported by women with a diagnosed bleeding disorder, possibly due to lack of treatment; further work is needed to explore this issue.