As people with haemophilia are living longer, there is a need to understand how to manage conditions associated with increased age, such as multiple myeloma, where standard treatment protocols involve the use of antithrombotic prophylaxis

© Shutterstock

Haemophilia A (deficiency of coagulation factor VIII) is a commonly recognised bleeding disorder with a UK prevalence of between 1:5,000 and 1:10,000 males [1]. Prophylactic factor replacement therapy and more recently the use of bispecific monoclonal antibody, emicizumab (first commissioned on the NHS in England in July 2018 [2,3]) have dramatically changed the prognosis of persons with haemophilia (PwH). With improved life expectancy, PwH are now more likely to suffer from conditions associated with advanced age; thus interdisciplinary management will be increasingly important.

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell dyscrasia with an incidence of approximately 5,500 patients per year in the UK [4]. Management of this condition has improved dramatically with the introduction of several new treatment options including immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) like thalidomide, lenalidomide and pomalidomide. Although very effective in improving the long-term outcome of patients with myeloma, IMiDs significantly increase the risk of thrombosis, particularly during the first six months of treatment. Managing the thrombotic risk can be challenging in selected subgroups of patients, such as those who develop venous thromboembolism (VTE) despite taking VTE prophylaxis or patients with coagulation disorders. In this report, we describe a young adult with severe haemophilia A diagnosed with MM, who went on to successfully complete IMiD-containing induction chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (SCT). He continues to be in remission on maintenance treatment for MM while receiving emicizumab, with no thrombotic complications throughout the treatment period.

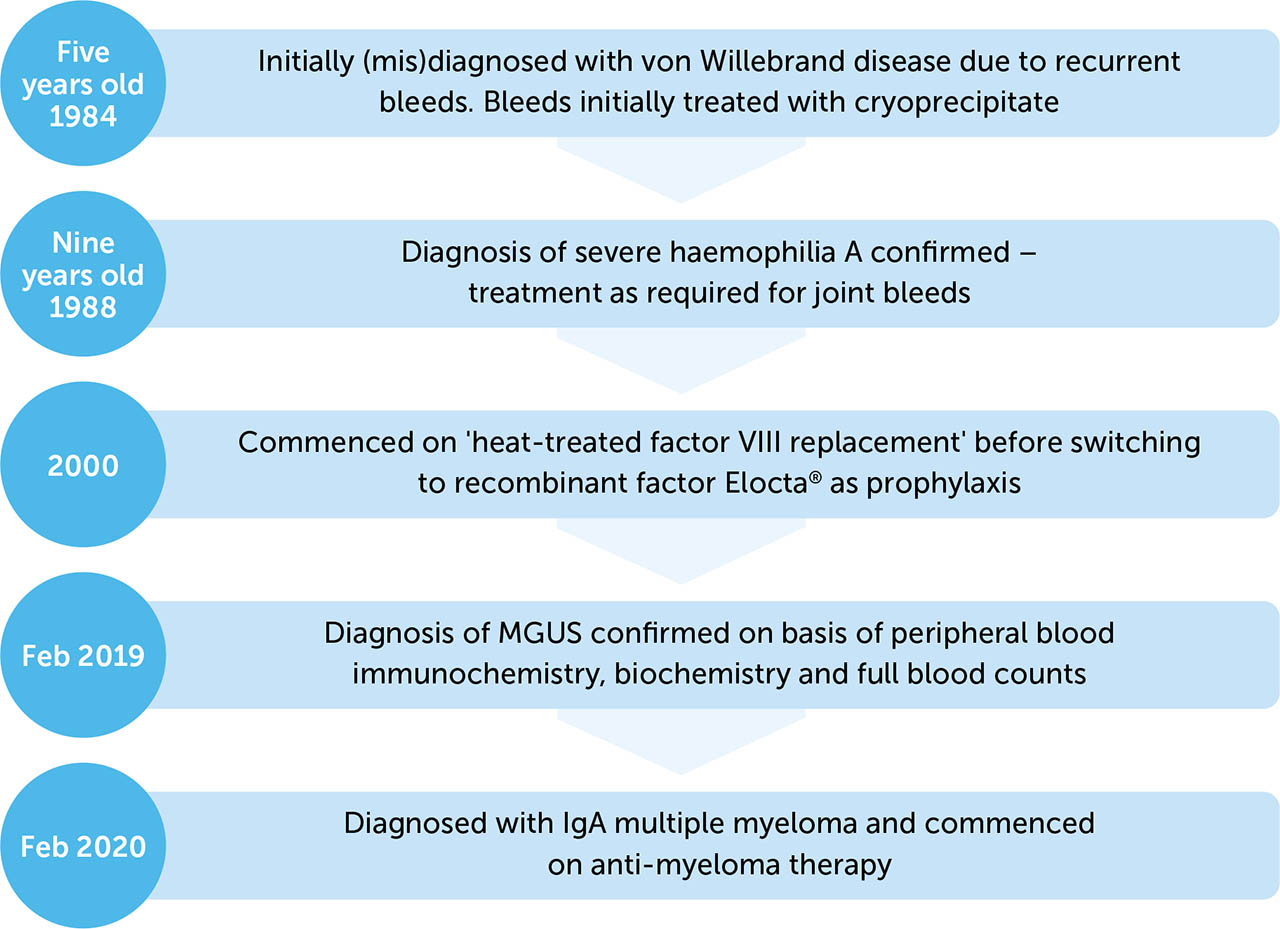

PATIENT INFORMATION

The patient was a 42-year-old (Indian Asian) male with a background of severe haemophilia A (see Figure 1). His haemophilia was well managed at a regional comprehensive haemophilia care centre, and he had not suffered any significant joint bleeds for almost ten years. He was previously successfully managed with recombinant factor VIII, efmoroctocog alfa (Elocta®) 2000 units every three days. His past medical history was also notable for a diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), for which he had been under surveillance with interval blood monitoring. After 12 months of stable disease, the patient progressed to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (MM).

CLINICAL FINDINGS

The patient was asymptomatic at the time of progression from MGUS to MM: examination was unremarkable, with no clinical features of MM identified. On examination, the patient had bilateral joint arthropathy of elbows and ankles, secondary to previous bleeds. These had been previously treated with corticosteroid injections and ankle fusion surgery.

DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT

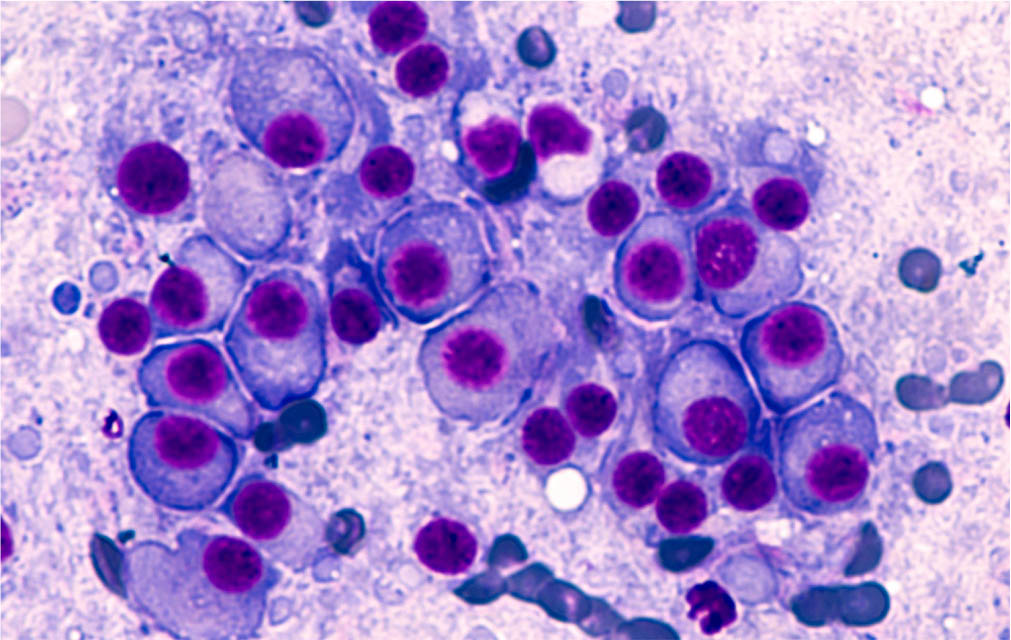

Progression from MGUS to MM was confirmed via a bone marrow aspirate and trephine, with plasma cells accounting for greater than 40% of total nucleated cell count. This intervention was prompted by a progressive neutropenia on peripheral full blood count and an increased IgA lambda paraprotein of 40.5g/L on immunofixation.

THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTION

After a detailed discussion about the advantages and disadvantages of various MM induction regimens, namely VCD (bortezomib (Velcade®), cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone) or VTD (bortezomib (Velcade®), thalidomide and dexamethasone) as per UK NICE guidelines, the patient chose VTD chemotherapy as it is demonstrated to achieve a deeper remission rate [5]. Due to the risk of thrombosis with thalidomide, thromboprophylaxis with low molecular heparin (LMWH) was planned. Dalteparin 5,000 units was given on the day of Elocta®, administered 30 minutes post Elocta® dose. For the next two days (i.e. without factor VIII replacement), the patient administered 2,500 units dalteparin. There was a subsequent switch to enoxaparin, the LMWH of choice at his local hospital, with an equivalent dose regimen of 40mg on the day of Elocta® followed by two days of 20mg/day. Towards the end of his first five-week cycle of chemotherapy the patient experienced an elbow bleed, on day two after his Elocta® dose (last day of enoxaparin prophylaxis). The patient’s most recent factor VIII trough level on Elocta® was 17iu/dl with no evidence of an inhibitor. The subsequent plan was to intensify Elocta®, omit enoxaparin and re-commence the anticoagulant after resolution of the bleed. However, the bleed continued to be a problem two days later. After detailed discussion about the thrombotic risks, the patient was commenced on emicizumab at the standard dose. He was informed of the absence of published data on co-prescribing of emicizumab with IMiDs. Elocta® was continued alongside emicizumab for the initial four weeks. Enoxaparin prophylaxis was re-instated one week after the commencement of emicizumab at a dose of 40mg once daily. Thalidomide treatment was paused until LMWH prophylaxis could be safely re-started.

FOLLOW-UP AND OUTCOMES

The patient experienced no further bleeding episodes, and successfully completed four cycles of VTD chemotherapy, achieving serological complete remission (CR), consolidated by high dose therapy and autologous SCT in November 2020. Standard hospital treatment protocol for thromboprophylaxis was employed throughout the transplant admission; 5,000 units daily dalteparin until a fall in platelet threshold of 50x109/L, following high dose therapy and SCT, at which point the daily dose was omitted until platelet recovery to >50x109/L. At around 100 days post-SCT, response assessment showed continued serological CR and the patient commenced lenalidomide as standard of care maintenance therapy [6]. Lenalidomide maintenance will be continued until progression of disease, intolerance, or patient choice to discontinue. He was also commenced on low dose aspirin as thromboprophylaxis, following a detailed discussion about the incidence of thrombotic events associated with maintenance therapy in patients achieving remission, international guidelines [7] and patient preference.

DISCUSSION

Bortezomib (Velcade®)-containing regimens are optimum first line therapy in young fit patients eligible for SCT [8]. Among the UK NICE approved and reimbursed combinations, bortezomib can be combined with thalidomide and dexamethasone (VTD) or cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (VCD). The overall response rate and, in particular, very good partial response (VGPR) and partial remission (PR) rates have been shown to be significantly higher with VTD when compared to VCD [5], although a slightly higher toxicity has been reported in patients receiving VTD. Additionally, bortezomib-related thrombocytopenia can be exacerbated by the cytotoxic effect of cyclophosphamide, hence can be particularly hazardous in the context of an existing bleeding disorder.

The risk of VTE in cancer patients is higher than that of the general population and in haematological cancers even more so, with particular risk for MM patients. The combination of thalidomide with high dose dexamethasone in induction regimens for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM), further increases the risk of thrombosis, with an incidence reported to be as high as 26% in the absence of any prophylaxis [7]. Thrombosis remains frequent in NDMM patients receiving IMiDs, (>10% incidence of VTE in thalidomide induction regimens), despite International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG)-guided thromboprophylaxis [7]. The risk of thrombosis is less in IMiD maintenance therapy than in NDMM induction regimens; however, in a recent phase 3 randomised controlled trial of lenalidomide maintenance versus no maintenance, significantly more patients in the lenalidomide maintenance group than the observation group had a VTE [9].

There is an absence of prospective randomised controlled trials of VTE prophylaxis in patients with haemophilia. Therefore, a pragmatic approach to assessing bleeding risk associated with the use of anticoagulants in these patients considers four relevant factors: the clinical bleeding phenotype of the individual, the type of anticoagulant, the intensity of anticoagulation (with LMWH being regarded as low intensity) and the period of planned treatment. Higher intensity anticoagulation is associated with increased bleeding risks, and therefore clinicians should opt for using intense regimens for short durations alongside clotting factor replacement or reducing the intensity of regimens for those with significant personal history of bleeding [10].

Emicizumab, a humanised monoclonal modified immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) antibody with a bispecific antibody structure, has revolutionised the care of patients with severe haemophilia A. It bridges activated factor IX and factor X to restore the function of the missing activated factor VIII that is needed for effective haemostasis [11]. An intraindividual comparison subgroup analysis of the HAVEN 3 study demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in annualised bleeding rate than previous factor VIII prophylaxis [12]. Although more than half the participants in this study receiving emicizumab prophylaxis had no treated bleeding events, the concurrent use of a factor VIII product (in the absence of an historic inhibitor, as would be the case with our patient), or a bypassing agent (if there is a previous known inhibitor) may be necessary in situations for breakthrough bleeds or interventional procedures. Should a bypassing agent be required, current literature recommends the use of recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) [13].

In summary, the case reported here demonstrates the successful management of a patient with severe haemophilia A and multiple myeloma in an area of limited data. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of emicizumab demonstrate a more prolonged steady state of the drug, with less of the ‘peaks and troughs’ associated with traditional factor concentrate [14]. This should provide a better protection against bleeding, thus permitting the co-prescription of anticoagulant drugs – something we would previously be reticent to do. As the haemophilia population ages, they may collect co-morbidities that require prescription of anti-platelet and anticoagulant drugs. The use of emicizumab may well allow the treating clinician to balance the pro and anti-thrombotic needs of this challenging to treat patient group.

PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

“I cannot praise the Haemophilia and Myeloma team enough for the care, support and overall patient experience. From initial diagnosis there has been ongoing dialogue between the Haemophilia and Myeloma team and joint care. I have been kept informed throughout my patient journey, alleviating my anxiety during an extremely challenging period. The phrase used many times in the NHS is ‘patient at the heart of any decision making’ (patient-centred care); I have experienced this first hand during my myeloma journey, with informed consent and choice of treatment discussed and agreed with me. My myeloma/haemophilia journey during the cancer treatment period, including stem cell transplant, has been made easier by the team (consultants, nurse specialist, lead pharmacist) and I have had full confidence in the cutting-edge management of both conditions.”