Faced with medical guidance about treatment that can be unclear or difficult to relate to, people with haemophilia and their caregivers develop their own ‘mental models’ to help them navigate their condition – but this can lead to both limitations and risks in their everyday lives.

Living with haemophilia requires constant balancing of treatment and activity levels [1]. This balancing act can be associated with a high degree of uncertainty [1]. Furthermore, as haemophilia care is increasingly managed in the home rather than in hospital, the responsibility of navigating uncertainty and finding a model to follow increasingly falls on people with haemophilia (PwH) and, for young PwH in particular, on their caregivers [2]. This shift to home care could be putting additional pressure on carers to become experts in the condition and its care, and for many carers this could also result in having to deal with increased uncertainty [2,3,4]. Recent research suggests that ‘worrying’ may be an even bigger issue for carers today than before prophylaxis treatment was introduced [5].

The aim of this article is to explore the experience of uncertainty around protection and subsequent coping strategies for PwH. This includes an examination of the areas of uncertainty experienced by PwH, the forms of medical guidance they receive, and the mental models of protection they develop. Here, ‘mental models’ refers to a system of logic that people use to interpret and navigate the world around them [6]. Similar to the ‘explanatory models’ described by Kleinman (1980), mental models of care and protection can often differ between patients and health care providers [7]. The findings presented come from a large-scale ethnographic study exploring the everyday life of PwH across five countries in Europe, including their beliefs and experiences related to their condition, their treatment, and their personal ways of managing the condition. The overall results from this study are previously published [8].

METHODS

Historical and disease area context was provided prior to the initiation of interviews by five haemophilia experts to help frame the research design. The experts included a specialist nurse at a paediatric haemophilia treatment centre (co-author NM), a practicing psychologist for people with haemophilia (co-author ATO), a physiotherapist, an anthropologist, and a medical psychologist working within the area of haemophilia. Qualitative methods were used to collect and analyse data. The study employed a multi-tiered grounded theory approach and gathered data through semi-structured interviews (with PwH, their family members, health care professionals (HCPs) and experts), facilitated group dialogues, written exercises, and on-site observations of the interactions of PwH with friends, family, and HCPs. Researchers observed PwH consultations with HCPs when agreed upon in advance with both parties. Study researchers used audio recording, video, photography, and extensive field notes to capture data, and the combined data was analysed using various approaches (e.g. inductive and deductive analysis, challenge mapping, and clustering exercises). The in-depth nature of the interviews and observations (researchers spent one to two days with each participant) allowed researchers to uncover the underlying needs and challenges faced by PwH, as well as unearthing ‘softer’ experiential metrics, such as the aspirations, fears, doubts, and attitudinal shifts currently dominating the discourse within the European haemophilia community. All statistics in this article are based on analysis of self-reported participant information. Further detail on the methods and sample of this ethnographic study can be found in the first publication of its results [8].

Recruitment

PwH were recruited for this study in Italy, Germany, Spain, UK, and Ireland through patient organisations in each country. The recruitment criteria aimed for a representative sample of PwH, screening candidates by haemophilia type, disease severity, treatment regimen, presence of inhibitors, and age range (under 12, 13–18, 19–49, 50+). HCPs were recruited for a mix of experience levels as well as representation of larger and smaller clinics.

Ethical considerations

PwH and HCPs participating in the study signed a GDPR-compliant consent form, which informed them of the terms of participation and the way their personal data would be managed. The study was conducted following the ethical standards outlined by the ICC/ESOMAR International Code on Market and Social Research [9], which sets out global standards for self-regulation for researchers and data analysts, as well as relevant national standards for participating countries [10,11,12,13].

Given the highly personal nature of the data collected in this study, participants’ privacy and anonymity were of high priority. Personal data was handled with the utmost care. In order to identify the different participants, while preserving confidentiality, each participant in the study was assigned a unique number. In the text of the article, quotes and cases are labelled with the participant's age range (e.g. teenager). All potentially identifying information about participants has been omitted.

RESULTS

A team of researchers conducted 51 in depth semi-structured interviews with PwH A (n=42) and PwH B (n=9) aged 1.5 to 82 years of age and receiving a range of treatments. The majority (94%, n=48) had severe haemophilia, while 6% (n=3) had mild or moderate haemophilia. These interviews and on-site observations were undertaken over one to two days and often included the wider social ecology of the individual PwH, i.e. friends, family, and caregivers. In addition, 18 HCPs from seven haemophilia treatment centres (HTCs) were interviewed. On-site observation was conducted at six of these HTCs, with and without patients, over the duration of approximately a half a day.

The study findings around PwH's experience of uncertainty is further explored and grouped into two sub-themes: general experience of uncertainty and perceptions of protection. Some calculations are based on 50 respondents rather than 51 as data for one respondent was incomplete.

General experience of uncertainty

1

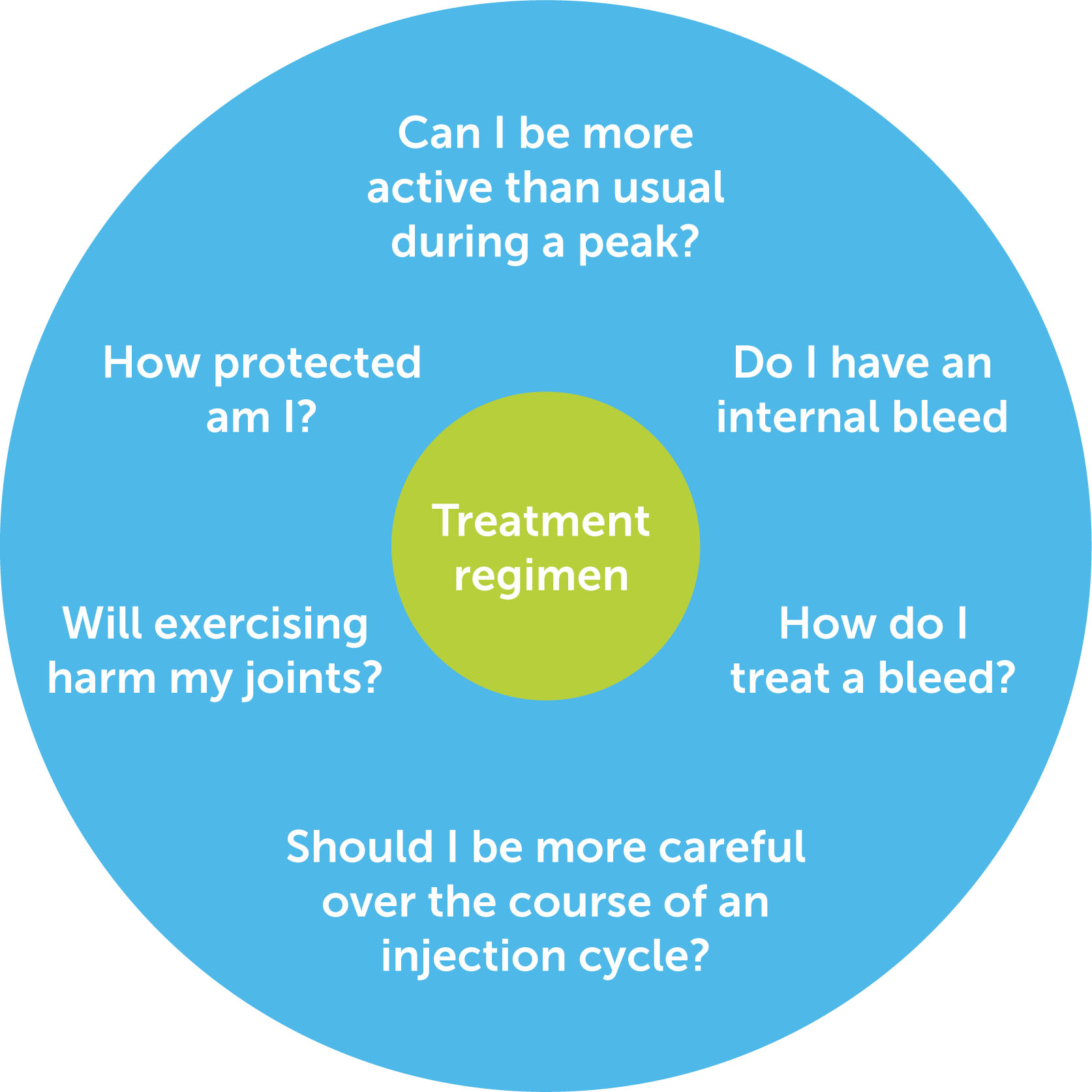

The study found that, despite adherence to a treatment regimen, uncertainty around protection is pervasive. In our sample, 52% (n=26/50) of PwH described experiencing significant uncertainty around the limitations and possibilities of their treatment regimen. Furthermore, 36% (n=18/50) of PwH who were adherent to prophylaxis treatment expressed worry about not being sufficiently protected and 78% (n=40/51) limit their activities because of their condition. The majority of PwH in our study described experiencing a general feeling of uncertainty, or ‘grey area’ as one participant described it, around their condition and treatment regimen in daily life (see Figure 1). There appeared to be some decrease in uncertainty with age and associated increased familiarity with the disease and treatment, however it is unclear to what degree this relates to improvements in care.

Figure 1

Illustrative diagram of the ‘grey area’ of uncertainty around treatment regimen among PwH, with example concerns

Many participants experience uncertainty because they feel that protection levels at any moment are difficult to assess. For example, one young man (20s) described experiencing uncertainty about his protection as he has weekly bleeds, even though he diligently follows his prophylaxis treatment. Many participants also described feeling uncertainty because the impact of activities on health outcomes is difficult to predict. Participants described being faced with trade-offs in terms of level of physical activity and protecting their health, both in the long and short term. This can present in the form of uncertainty about experiencing bleeds as an immediate result of an activity. For example, an older participant (50+) described taking walks regularly but always being ‘worried’ because he does not know how hard he can push himself before experiencing a bleed. This uncertainty can also present in the form of concern about long-term joint damage as a result of an activity. Participants often felt that the future impact of a bleed on joint health was unclear, as one boy's (child) mother described:

In another example of the experience of uncertainty around future consequences, a young woman (20s) who has severe haemophilia feared the possibility of needing a wheelchair later in life and has therefore decided to never walk more than 500 metres in one day.

Many young PwH in the study described experiencing uncertainty as a result of not having a clear approach to follow from their family. Those without a family history often felt alone with their haemophilia. For example, one young man (20s) described being the first in his family with haemophilia:

“This means that I didn’t grow up with the perspective of previous generations and the crises they experienced.”

However, PwH with a family history of the disease sometimes described looking to the experience of previous generations as irrelevant at times because older family members with the condition offer an outdated model to follow. For example, one boy's (child) grandfather had haemophilia, but his mother did not find this helpful:

Perceptions of protection

2

In the face of uncertainty around their condition and protection, our data indicated that many PwH understand protection in a way that differs from medical advice. They may be aware of the mechanisms of action of their treatments but make varying interpretations about how it influences protection and bleeds, and what level or type of activity it enables. These ‘mental models’ of protection seldom matched the view of the medical community and thus could potentially lead to suboptimal results. For example, mental models led some PwH to engage in risky behaviour and others to hold back from activities when it is not medically necessary.

A little more than half of the PwH in the study (52%; n=26/50) struggled to translate the clinical understanding of protection into specific activities in everyday life. While most of the HCPs interviewed described trying to communicate the level of protection provided by the treatment regimen in a way that empowers patients to plan their activities, many PwH described the communication as ‘vague’ or conflicting. For many it is unclear how protected they are. For example, they find it hard to know when exercise might harm their joints, what type of activities are safe at what point, how protected they are at any given point, and so forth. One HCP reflected on why PwH may get confused:

“It's important to not scare people off and let them think that they need a factor level of 80 to do activities. But I am still trying to have people do treatment as soon as possible before activity.”

In addition to this lack of relatable medical guidance on protection levels, many PwH in our study described not receiving adequate information on how to use new treatments after switching. For example, a teenage participant and his father were not told how to manage bleeds after switching to a new treatment and therefore had to figure out their own way to handle this. Hence, the teenager was left to do what he thought was best based on his previous treatment regimen, as explained by his father:

“You were never told what to do if you have a bleed. Do we go to the hospital? Do we administer an extra injection? Should it be 3,000? 5,000?”

Many families described having to figure out what protection meant for them through trial and error in the absence of a clear understanding of medical advice. An example of this is when a teenage participant wanted to start the sport of fencing. When his mother looked through the brochure she had received from their doctor, it said that doing physical activity is essential for people with haemophilia, but listed a number of activities as either ‘suitable for most patients’, ‘suitable on a limited basis’, or ‘problematic’. When her son really wanted to start fencing – a sport listed as ‘problematic’ – she decided that fencing, despite being ‘problematic’, might be better than no exercise at all. She then pursued a ‘wait and see’ approach, and only informed the doctor after the fact.

In another example of how personal experience, in the absence of relatable medical guidance, can lead to highly individual interpretations, the mother of a young participant (child) has developed a mental model around how factor levels influence protection. She considers her son safe to engage in most activities on the injection day and unsafe on all other days, where activities are consequently restricted as much as possible. She explained, “The days without treatment are my ‘worrying days’.” On days with treatment she considers her son to be completely safe and allows him to do most of the things the nurse has told her he can do. However, on non-treatment days she believes his factor levels are practically zero and therefore tends to significantly limit his activity. On these ‘worrying days’ she goes as far as using a leash tied to her son's backpack when they are outside of the home. The mother's mental model of protection has resulted in her being overly cautious, severely limiting her son's activities based on her estimation of his level of protection. Several other parents shared this mental model of protection.

DISCUSSION

The results from this study show how PwH deal with significant uncertainty around haemophilia treatment and care, ultimately developing mental models to make sense of protection and guide their actions that often differ from the medical community. The issue of uncertainty relating to treatment may become increasingly important with the changing treatment landscape. While existing literature also suggests that PwH develop highly individual notions of protection in order to cope with this uncertainty and the complexity associated with the condition and treatment regimen [14], this study explored how this plays out in everyday life and how misunderstandings of information or insufficient information can create uncertainty in many ways for PwH. Existing research indicates that PwH often do not have enough information about bleed identification and management [15,16] and that many PwH feel misinformed or inadequately informed by HCPs [17]. The results of this study show how uncertainty around protection levels can make some decisions in daily life more difficult for PwH, e.g. the decision of whether or not to do certain physical activities and sports, resulting in either overly risky or overly cautious behaviour. Furthermore, the results indicate that a lack of certainty about protection levels being sufficiently high can contribute to a general sense of unease around their condition and long-term health.

This analysis explored PwH's approach to incorporating medical advice on protection into their lives, showing that PwH create their own mental models of protection, i.e. health and disease guidelines, which inform their decision on why some activities are ‘allowed’ while others are not [2,4]. This process could be influenced by sources that do not have the same clinical knowledge as HCPs, e.g. local social norms, previous personal experiences of bleeds, or the experiences of family members or others in the haemophilia community [18]. The creation of mental models in response to complexity and lack of adequate guidance is well documented in the behavioural economics literature [19] and has also been shown to impact decisions around health: “To make the complicated necessary decisions repeatedly in daily life, they [people] use heuristics or rules of thumb rather than going through all possible choices” [14]. Research indicates that this type of bias is particularly challenging for people who are faced with more high-stakes decisions, such as those with low socioeconomic status or those living with a chronic illness [20].

On the other hand, research in other disease areas suggests that PwH's personal interpretations of medical information about their condition and personal coping strategies can have value in terms of how they navigate their condition [7]. The power of patient-centric information can be seen in studies suggesting that the burden of care seems to decrease with the exchange of information from patient to patient [21]. This raises a crucial point: while PwH's unique mental models can lead to poor treatment results, it is important to understand how these models came to be (in terms of a patient-centric understanding of the experience of uncertainty) in order to create guidance that fits with PwH's lived experience of the condition, and is thereby easily internalised by PwH. As treatment continues to improve and care becomes more independent, patient uncertainty around protection could increase. Patients are moving toward greater independence from haemophilia centres, and while clearly desirable, this also means that opportunities for information sharing between PwH and HCPs is diminishing.

Limitations of the study

The findings described above are representative of patterns observed across several European countries. However, the data from this study were not sufficient to produce an analysis of country-specific differences within Europe. Further investigation is needed to produce a more comprehensive analysis of patient needs at a country level. It is also important to note the potential of self-selection bias in the volunteer-based recruitment approach.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that there is currently not adequate support for PwH in dealing with uncertainty around their condition and treatment regimen. Whether PwH look to family members or look for direction from the medical community, they experience a lack of guidance. PwH in our study often found HCP communication around protection levels confusing. The mental models they have developed around protection in the face of this lack of clarity can cause distress and influence their behaviour in a way that limits possibilities, and/or increases risk.

More patient-centric guidelines could help bridge the gap between PwH and HCP understandings of protection, allowing PwH to more effectively translate medical knowledge about protection levels to decisions around activities in their daily life, as well as providing a greater general sense of wellbeing and safety. The results of this study clearly suggest a need to develop and improve tools and communication materials that can better help PwH translate and internalise what their treatment regimens mean in terms of level of protection in everyday life, to enable them to better assess if and when certain activities are safe. Although further research in this area is needed, the current communication gap between how the medical community and PwH understand protection could be addressed by supporting and encouraging HCPs to communicate in a more patient-centric way, i.e. by addressing which activities relevant to individual PwH are possible and when to engage in them, or communicating that for certain activities a change in treatment regimen is needed. HCPs could also benefit from tools that allow them to better assess and address the mental models their patients have developed in order to align their understanding of protection. As PwH learn from and put a lot of trust in other PwH, it is important that patient organisations take part in helping to communicate a patient-centric model for understanding levels of protection and assessing appropriate activities. If PwH and their carers have a clearer idea of if and when they are actually protected, it will help them maximise the possibilities they have in life.

DISCLOSURES

This study was carried out by ReD Associates with funding from Sobi. Sobi and Sanofi reviewed the article. The authors had full editorial control of the article and provided their final approval of all content. TH, MBK, YG, AML, and ABL are employees of ReD Associates. ATO is a researcher at the University of Murcia. NM is a researcher and nurse at Alder Hey Children's Hospital. JS is an employee of Sobi.