Pain in people with haemophilia remains an ill-defined and treated comorbidity. This study looks at its prevalence, severity, influencing factors and management across a range of countries, and calls for age and developmentally appropriate pain assessment in routine care.

Haemophilia is an inherited X-linked bleeding disorder, caused by mutation of the gene encoding for clotting factor VIII (8) or IX (9) (FVIII, FIX). The severity of the bleeding disorder depends on the activity of factor in blood: severe is defined as <0.01 IU/dl (<1%), moderate as 0.01–0.05 IU/dl (1% – 5%) and mild as >0.05 IU/dl (>5%) [1]. Haemophilia causes recurrent bleeds from early childhood, most commonly in weight-bearing joints, which are painful and predispose to arthropathy, muscle atrophy and deformity [2]. Treatment of bleeds may delay but does not prevent this process.

Optimal management for people with severe haemophilia involves prophylaxis with regular infusions of FVIII or FIX, which helps to reduce the risk of bleeds and joint damage [3]. However, this is expensive and frequently not an option in economically developing countries, where people with haemophilia (PwH) more commonly receive on-demand treatment with factor replacement only when bleeding occurs [4–5]. Children and adults with mild or moderate haemophilia also receive on-demand treatment. However, on-demand treatment causes delay in administration of replacement factor and is associated with an increased risk of complications such as joint damage at an early age [6].

Joint pain is common in PwH and is recognised as a burden that impairs quality of life (QoL) and has been shown to worsen with age [7,8,9]. Pain management is challenging because some analgesics, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines, are contraindicated in PwH [7] and access to non-drug therapies may be limited [8,9]. Individuals may use therapies such as acupuncture, marijuana and other complementary medicines [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17], but information about which therapies they use and their effectiveness is limited.

Pain is defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” [18]. Acute and chronic pain are distinct processes calling for distinct and specific assessment and intervention strategies. Acute pain is provoked by a specific disease or injury and is associated with skeletal muscle spasm and sympathetic nervous system activation; it serves a useful biologic purpose (prompting a defence against injury) and is self-limiting [19]. By contrast, chronic pain may be considered a ‘disease state’: it outlasts the normal duration of healing, serves no biologic purpose, may arise from a psychological state, and has no recognisable endpoint [19].

Treatment of acute pain, such as following a joint bleed, aims to interrupt nociceptive signals and correct the underlying cause, whereas the therapy of chronic pain relies on a multidisciplinary approach and involves more than one therapeutic modality [20]. There is overlap between the symptoms of acute pain due to bleeding and chronic pain associated with arthropathy in haemophilia, and PwH can find it difficult to distinguish between them [21,22].

There is also some evidence to suggest that the issue of pain in PwH may not always be adequately addressed by health care professionals (HCPs) in haemophilia treatment centres (HTCs) [22]. Clinical practice is largely empirical and varies widely with a “lack of data and standardised guidelines for pain management” [7]. Together, these factors mean that the treatment and management of pain in PwH remains an issue. The assessment of pain in PwH continues to be based on a biomedical model focused on the presence of joint damage or bleeding, rather than the individual's experience of persistent pain.

This study aimed to establish greater understanding of the experience of pain in PwH in different countries, its prevalence and severity, the factors that influence this, and how pain is currently managed. At the time of the study, no disease-specific instrument had been designed to measure pain in PwH, although instruments developed for other conditions have been shown to be useful [23].

METHODS

A convenience sample of a maximum of ten consecutive PwH attending HTCs in 11 countries (China, Croatia, Denmark, England, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Spain and the USA) were asked to complete an anonymous questionnaire over a maximum of three months to get as close to the convenience sample number of 10 PwH per centre as possible. The data collected included demographic information (age, disease type/severity, joint health, number of bleeds), and information about their pain, use of analgesia, other methods of pain relief and other medication.

We captured patient responses about pain using the validated EQ-5D (3L) instrument [24], supplemented by further non-validated specific questions focused on the patients’ experience of pain during the preceding 28 days. EQ-5D is a widely used, standardised instrument for measuring health status as it relates to overall quality of life and is available in the languages of all countries covered by the study. It incorporates a question about pain and has been shown in other studies to be responsive in its measurement [25,26,27]. EQ-5D's ‘Usual activities’ subscale enabled the collection of data on participants’ ability to carry out their day-to-day activities.

The non-validated part of the questionnaire comprised 30 questions which asked about: patent demographics; site, severity and duration of pain; presence of target joints; surgical intervention; analgesia use; other medicine use, including haemophilia treatment and non-medical pain control. A Likert scale was used to ask questions about how well pain was managed by haemophilia team staff, impact of analgesia either prescribed by the HTC or bought over the counter, and complementary therapies. The questionnaire was translated into local languages by the site staff if necessary; there was no validation of this translation.

Pain frequency was determined by the number of days on which participants experienced pain during the preceding 28 days. Pain severity was assessed by the scale for pain/discomfort in the EQ-5D quality of life instrument. Health status on the day of assessment was captured using the EQ-5D VAS scale ranges from zero (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state).

PwH who were unable to read or write or who did not consent were excluded. To minimise possible parental bias, children aged ≥8 years self-completed the questionnaire where possible. If they required help this was given by the study coordinator rather than a parent/caregiver to reduce parental influence and bias.

Data collection was carried out by nurses or study coordinators at HTCs identified through the Novo Nordisk Global Haemophilia Network (GHN).

Ethical approval

The study was registered at each participating site in accordance with local clinical governance arrangements. Participating sites were required to confirm their obligations with regard to ethical approval prior to commencement of the study. Full ethical approval was not deemed necessary by some sites who followed the King's Fund Experience Based Co-Design Toolkit guidance [28], which states that for studies that do not change clinical practice, ethical approval is not necessary. At sites where ethical approval was deemed necessary this was granted by local regulators. All study participants were required to consent to participate in the study.

Data analysis

To explore the occurrence of pain in PwH, we analysed the sub questions in the EQ-5D related to pain (‘no pain’, ‘some pain’, ‘a lot of pain’) and the VAS scores rating analysis of health status on the day of questionnaire completion. The impact of pain and how PwH treated and viewed it was assessed from answers to questions on the non-validated questionnaire.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

A total of 209 persons with haemophilia A or B of any severity (median age 36, range 8–84) from 20 HTCs in 11 countries (China, Croatia, Denmark, England, Israel, Japan, Malaysia, The Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Spain and the USA) participated in this study, with England, Malaysia, The Netherlands and USA having multiple HTC involvement. Table 1 summarises the participants’ demographics, including haemophilia type and severity, inhibitor status, age, treatment regimen, and reason for visiting the HTC on the day of completing the questionnaire.

Table 1

Participant demographics (N=209)

Pain

Forty-seven participants (21.5%) reported no pain at all in the preceding month. Of the remaining 161 PwH (data missing on one) a total of 1945.5 days (164.80 days per year) of pain were reported, with 29 (18.8%) reporting pain on a daily basis. Twenty-nine PwH (13.8%) completed the questionnaire on a day that they were attending the HTC because of a bleed – this may have been an acute presentation or for follow-up.

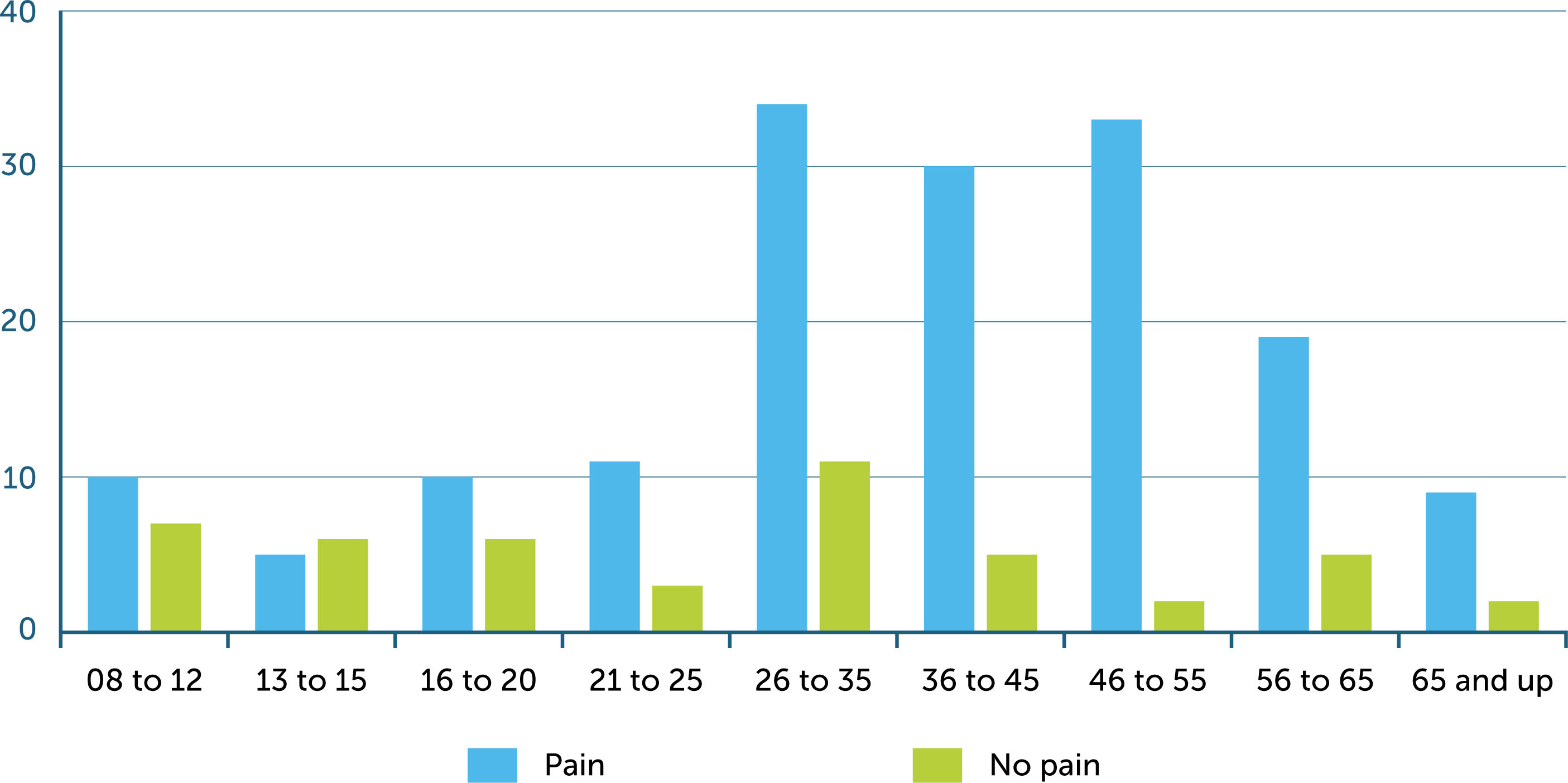

Patients with severe haemophilia reported the most pain and patients with moderate haemophilia the lowest pain but there was no significant difference in pain between severities (P=0.39). PwH with an inhibitor reported a greater level of pain than those without but this was not statistically significant. Of those PwH who had experienced pain (n=161), which was present in all age groups and appeared to increase with age (Figure 1), joint pain was reported by 106 (65.8%), muscle pain by 45 (27.9%) and both joint and muscle pain by 10 (6.3%).

Pain not related to haemophilia was also reported, with some PwH reporting headaches, for example. The overall pain levels across treatment regimen and severity were almost equal, with differences ranging from −16% to +24%. None of these differences were significant.

Pain management

Just over one third (34.2%) of the 161 participants who reported pain stated actively discussing pain with their haemophilia care team; others reported discussing their pain with family/friends and other physicians. Questions supplementary to the EQ-5D asked about pain management advice from the haemophilia team, which this group of participants reported was poor. One hundred and eighty-four PwH provided data relating to being asked about pain during visits to their HTC; 18 (9.8%) reported that pain was not discussed, and a further 8 (4.8%) felt that they did not receive sufficient advice on pain management. Pain management was reported in two ways, analgesic and non-analgesic strategies, and are described further below.

Analgesia use

Twenty-five participants (15.5%) reported choosing not to take analgesia because it might mask the resolution of a bleed. Two thirds of participants who reported analgesia use stated they became pain free using simple analgesia alone. The participants who reported the most pain (n=57, 35.4%) used analgesia on a weekly basis. Of these, 78 (37.3%) took paracetamol, and 25 (43.8%) reported using at least one other type of analgesia (including codeine, COX-2 inhibitors, non-COX selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or opioids). Sixty-four participants (39.7%) reported using analgesia that had not been prescribed by a health care provider. Forty-six PwH (28.5%) responded that their pain could not be relieved by analgesia.

Twenty-four of the 25 PwH who reported never using analgesia conversely reported that ‘painkillers are enough to relieve them of their pain completely’ on the questionnaire. It is unclear whether they were describing pain related to haemophilia, other pain, or if they misunderstood the question.

Non-analgesia pain relief strategies

Forty-six PwH reported using non-pharmacological strategies to reduce pain including rest, physiotherapy, crutches or walking aids, alcohol, marijuana or other. There was some overlap in these questions as participants were able to give more than one response (i.e. they may use more than one strategy to reduce pain).

Usual activities

The EQ-5D VAS scores showed good overall mean scores with a decreasing median score within the increasing age groups (Table 2). On the non-validated questionnaire, 123 (58.9%) participants reported no problems with conducting their usual activities due to pain, 73 (34.9%) reported some problems, and 13 (6.2%) reported a lot of problems. There was no statistically significant difference between treatment regimens in the distribution of the level of problems PwH have with usual activities as a result of pain (p=0.49), and no evidence that PwH on prophylaxis had fewer problems with usual activities than those using on-demand treatment. PwH in non-western countries (China, Japan, Malaysia) reported greater difficulty performing usual activities than those from western countries (67.3% vs. 47%).

DISCUSSION

Health care providers recognise that PwH suffer pain, acutely when they bleed and long term as a result of joint damage, and yet we do little to treat it other than in an acute bleed situation, or to research the impact that is has on affected individuals. Humphries et al. had a call to action in 2015 to prioritise pain management in haemophilia [29] and in 2018 Roussel reported on the complexity of managing pain in PwH [20]. However, there remains a paucity of information about effective pain management for PwH.

Our study showed that one in five PwH reported daily pain and almost three out of four PwH experienced pain within the previous 28 days, regardless of geographical constraint to treatment access or, indeed, treatment modality. Whilst there were numerical differences between PwH with severe and less severe haemophilia, and between those with an on-demand treatment regimen compared with those on prophylaxis, these differences were not statistically significant, perhaps because of small participant numbers, or because pain caused by bleeds and subsequent arthropathy occurs regardless of haemophilia severity.

Despite this, the subjective experience of both haemophilia and pain are important. Having an inhibitor increased the likelihood of reporting pain and was statistically significant; this can be attributed to the increased likelihood of bleeding with inhibitors, the reduced response to treatment and a lack of prophylaxis options at the time of the study. Age increased the reporting of pain and was statistically significant; poor recognition and treatment of pain in children with haemophilia has been reported [9] and warrants further research. Living with a baseline level of pain, due to joint disease in PwH, is highly likely and leads from emotional distress in children and caregivers to anxiety and depression in older PwH [30].

Forty-six PwH (28.5%) responded that their pain could not be relieved by analgesia, whilst almost two thirds reported adequate pain relief with simple analgesics, which they reported to have bought ‘over the counter’, and yet half of respondents had not discussed their pain with their haemophilia care team. Successful self-management of pain, and not discussing pain openly, contributes to the under-recognition of pain in PwH documented among clinicians [22]. Health care providers and some PwH can be reluctant to use stronger analgesia due to fears of addiction; however, a recent US publication reported that opioid use was higher in paediatric and adult practice than predicted [31]. Witkop and Lambing suggest that despite recognising PwH as the best source for reporting pain, HCPs don’t always recognise the importance of treatment and require ongoing education in pain management [32].

PwH also self-manage pain with rest, immobilisation and rehabilitation, physiotherapy, psychotherapy and use of orthotics [33]. Non-pharmacologic strategies for managing pain such as exercise [34] hydrotherapy [35], physiotherapy, and orthotic use were not frequently reported in our study, although we know that PwH seek alternative ways to relieve pain in a more holistic manner [12,13,14,36,37] than with analgesia use alone.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is the difficulty in comparison between the different countries due to treatment access, government regulations and health insurance. The study suffered from incomplete data responses within the questionnaire from some PwH, reducing the data available.

Pain is a difficult endpoint to measure because individuals may interpret the sensation differently – for example, what one PwH calls pain may be considered to be discomfort by another.

Although the EQ-5D has questions relevant to collecting data on pain, it is a general tool for measuring health-related quality of life and it was necessary to supplement it with additional non-validated questions specifically for the purpose of collecting data on pain in PwH. Since conducting this research, the Multidimensional Haemophilia Pain Questionnaire, a haemophilia-specific tool for measuring pain in PwH, has been developed and trialled in Portugal and should be used in future studies [38].

CONCLUSION

We conclude that pain in PwH remains an ill-defined and treated comorbidity, occurring with the first bleeding episode and increasing with age, probably related to haemophilic arthropathy from recurrent bleeds but possibly also due to osteoarthritis related to ageing. Pain is more than five times higher in PwH with inhibitors. With emerging therapeutic options for PwH and inhibitors bleed rate may be reduced, which may impact positively on pain. Geographical location (living in China, Japan, Malaysia) seems to have a significant effect on whether or not PwH have problems performing usual activities. This may be related to access to prophylaxis, an increase in number of past or current bleeds and/or presence of haemophilic arthropathy and associated pain. Age and developmentally appropriate pain assessment should become part of routine care and should include the haemophilia multi-disciplinary team, physiotherapy to improve functional ability, and psychological support to enhance coping skills which are as important as analgesia prescription.