Image: Properly managed physical activity has been shown to have haematologic, musculoskeletal and psychosocial benefits in people with haemophilia. Top rope climbing is an increasingly popular sport and tailored courses may be beneficial to those with arthropathic joints

© Shutterstock

While physical activity in patients with haemophilia (PWH) was discouraged before the advent of factor concentrates and prophylactic treatment regimens, the current standard of care in haemophilia incorporates regular physical activity [1,2]. Properly managed exercise in PWH has been shown to improve pain, range of motion (ROM), strength and walking tolerance, depending on the particular type of exercise [3]. studies also suggest many other haematologic [4], musculoskeletal [5, 6, 7] and psychosocial benefits [1,8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Due to improvements in muscle strength, joint stability, ROM and posture, regular exercise has been postulated to decrease the frequency of bleeding in PWH. Psychosocial benefits of exercise for PWH include improved self-perception, social inclusion and quality of life (QoL). Overall, exercise programs are a critical adjunct to clotting factor therapy in PWH [13].

A sports discipline appropriate for PWH should carry a manageable level of risk of injury and be adaptable to the patient's level of fitness, as well as be exciting so that patients are motivated to continue. Top rope climbing therapy is a novel athletic concept that may fulfil all of these elements for PWH. Climbing involves physical, technical and mental components including coordination, posture, flexibility and concentration, and has been applied as a therapy in various orthopaedic, neurologic and psychological disorders [14, 15, 16, 17]. Top rope climbing was classified as a low to moderate bleeding risk sport for PWH – similar to Pilates – in guidelines issued by the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF) in the United States in 2017 [18]. One case report and a case series with nine young haemophilia patients in Germany recently demonstrated that top rope climbing was not detrimental in young adult PWH on prophylactic clotting factor infusions [19,20]. In these patients climbing appeared to improve joint health and enhance quality of life, and motivated them to either begin or continue prophylactic factor treatment, which in turn contributed to reduced bleed rates.

The aim of this study was to evaluate positive as well as possible detrimental effects of top rope climbing therapy for adult PWH with severe joint impairments in an urban area in the United States. For these patients, athletic exercise and opportunities to walk are limited, and physical therapy and low impact activities are often considered boring, resulting in poor motivation and adherence.

Materials and methods

Patient population

Six adult male patients, age ≥ 21, with moderate to severe haemophilia A, and with arthropathies, were recruited from the Hemophilia Treatment Center at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Moderate and severe haemophilia were defined as a percentage of intrinsic factor VIII (FVIII) activity of 1-5% and less than 1%, respectively. All patients had one or more arthropathic joints, as defined by the Hemophilia Joint Health Score (HJHS) version 2.1 [21]. Patients with detectable inhibitors or inability to consent were excluded. The study was conducted in compliance with international guidelines on Good Clinical Practice and local regulations. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee, and written consent was obtained from all patients before enrolment.

Climbing program

All participants completed 12 weekly sessions of individually tailored indoor top rope climbing (a three-month program). Top rope climbing consisted of ascending a wall while protected by a safety rope running through an anchor at the top. A belayer (a companion on the ground below) kept firm control of the rope during the ascent. Participants were paired and switched between climbing and belaying, and each participant performed an equal number of climbs during the session. All sessions were instructed by a climbing coach and a licensed physical therapist, who collaborated to create an individualised program and set goals for each patient. The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) was used to prepare these individualised programs and follow progression of climbing skill throughout the study [22].

Clotting factor therapy

The patients continued their baseline standard prophylaxis throughout the climbing program, with standard prophylaxis consisting of 30–50 units per kilogram of recombinant FVIII at intervals of two to four days. They were also advised to plan their routine factor infusions to coincide with climbing training to ensure that they infused within 24–36 hours of climbing.

Data extracted and collected

The health history of each patient was extracted from their medical records. Age, haemophilia type and severity were recorded. Joint status was evaluated using the HJHS before and after climbing by a licensed physical therapist with over ten years of general practice experience, and approximately two years’ experience of working with haemophilia patients. The physical therapist was trained in the HJHS according to instructions and guidance provided by online training and video modules developed by the International Prophylaxis Study Group [23]. Normal and affected joints were defined as joints with a range of motion (ROM) within or outside of the normative ranges respectively, as defined by the HJHS version 2.1 [21]. For each patient, the total HJHS comprised six joints (two elbows, two knees and two ankles), with minimum and maximum possible scores of 0 and 120 respectively. Climbing skills were assessed before and after the program using the YDS system. The YDS (grade range: 5.0 – 5.15) graded climbing scales; higher values indicate a more technically difficult course. Beginners with moderate athletic skills without any previous climbing experience are generally capable of mastering YDS grades 5.5 to 5.7. QoL measures were assessed using the Haemophilia Quality of Life Questionnaire for Adults (Haem-A-QoL) [24]. Bleeding rates and clotting factor consumption were extracted from patient diaries in both cohorts before and after climbing, and were expressed as annual bleeding rates (ABR) and units/kg/month.

At the end of the study patients were asked for feedback in the form of personal interviews. The patients were asked specifically about their perception of the program, and whether it improved their motivation to adhere to their prescribed infusion regime.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound with power doppler (MSKUS/PD)

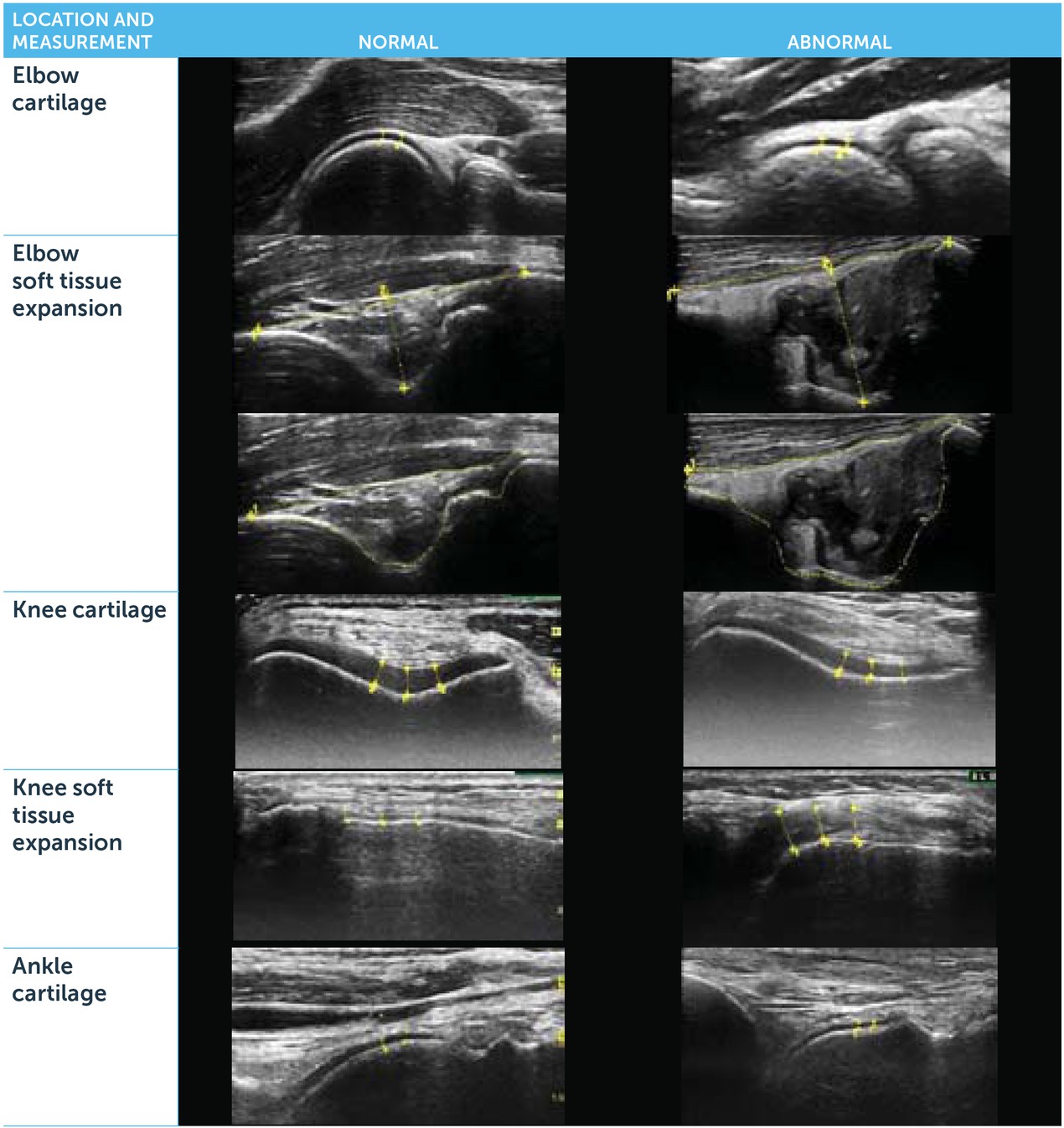

Arthropathic joints were evaluated with MSKUS/PD using a GE Loqiq S8 module (General Electrics, Fairfield, CT, USA) with real-time spatial compound imaging, speckle reduction capabilities, and an 8–16 MHz high frequency linear transducer. PD and greyscale examinations were performed in accordance with published standardised protocols [28, 29, 30], whereby the intensity of PD signal provides an estimate of the extent of intraarticular vascular perfusion abnormalities as an indicator of inflammation.

Effects on cartilage health, joint inflammation and soft tissue hypertrophy were assessed. Structures on MSKUS were quantified using the Joint Activity and Damage Exam (JADE) algorithm, utilising standardised transducer positions [28, 29, 30]. Cartilage and soft tissue thickness, comprising capsule, synovium and/or fat pads, were measured in sentinel locations with the transducer perpendicular to the bone. Soft tissue thickness was measured as a combined interface including joint capsule, fat pad and synovium, since these structures cannot always be clearly distinguished by echogenicity differences in pathological states.

For cartilage and soft tissue thickness, several measurements were placed 2.5–5 mm apart (distances pre-specified for each joint based on anatomy and tissue morphology) and averaged. Elbow measurements comprised the combined interface of capsule, synovium and olecranon fat pad within the posterior olecranon fossa; cartilage thickness was assessed on the humeral head. Knee synovial measurements were performed in the medial and lateral recesses; cartilage thickness in the femoral trochlea was determined with the knee in 90° flexion. In the anterior ankle, the combined interface of capsule, synovium and pre-talar fat pad was measured; cartilage thickness measurements were performed on the talar dome. Supplemental Figure 1 exemplifies the soft tissue and cartilage measurements for each joint.

Figure 1

The Yosemite Decimal System (YDS) measured changes in climbing skills during the study. All subjects started at level 6, between step 5 and 6 of the YDS

PD signal scoring to assess vascular abnormalities and inflammation was performed, where higher scores indicate increased vascularity and inflammation (score range 0–3) as previously described [29]. A dynamic sweep of the region of interest was completed and the highest signal seen for PD scoring was recorded.

All MSKUS studies were either performed or supervised by a haematologist who was formally trained in MSKUS, certified in MSKUS through the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography (ARDMS), and maintains certification aligned with requirements by the Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM). The haematologist was blinded to all other outcome measures.

Results

Baseline patient and joint characteristics

Six adult male patients with moderate to severe haemophilia A and with arthropathies completed the study. They ranged in age from 24 to 44 years (median = 31).

At baseline the median total HJHS for six joints (two ankles, two knees and two elbows) was 17.5 (range: 6 to 42). Two patients had a single arthropathic joint, two had two arthropathic joints, and two had three or more arthropathic joints (Table 1). Fifteen out of 36 (42%) joints (elbows, knees and ankles of all patients) were arthropathic at baseline. Of the arthropathic joints, seven were elbows, three were knees, and five were ankles.

Table 1

Baseline patient and joint characteristics

Climbing skills and clinical joint assessments

All six subjects started with a climbing skill of 5.06 on the YDS scale, and all improved substantially. The

median gain was four levels (Figure 1). Compared to baseline, total HJHS improved during the program in four of the six subjects, remained unchanged in one, and deteriorated mildly in another patient, resulting in a mild overall improvement from the median of 17.5 to 16.5. Arthropathic ankle (n=5) dorsiflexion improved with a median change of 3 degrees (range 1 to 9), while there was no change in ROM otherwise.

Quality of life (QoL) assessment

QoL assessment by Haem-A-QoL between the start and end of climbing therapy remained unchanged (median 31.0 before compared to 30.5 afterwards); however all participants voiced a meaningful increase in wellbeing and new confidence to overcome challenges.

ABR and clotting factor consumption

All subjects were on standard clotting factor therapy before and during the study. The median clotting factor consumption was 515 U/kg/month (range: 224 to 853) before and 499 U/kg/month (range 266 to 970) during climbing. Median ABR remained unchanged (median change = 0; range: -4 to 4).

Joint evaluation with MSKUS/PD in arthropathic joints

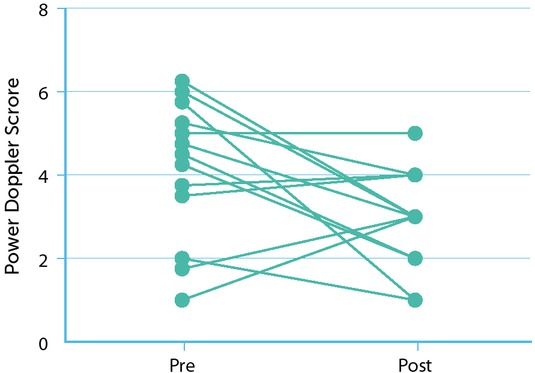

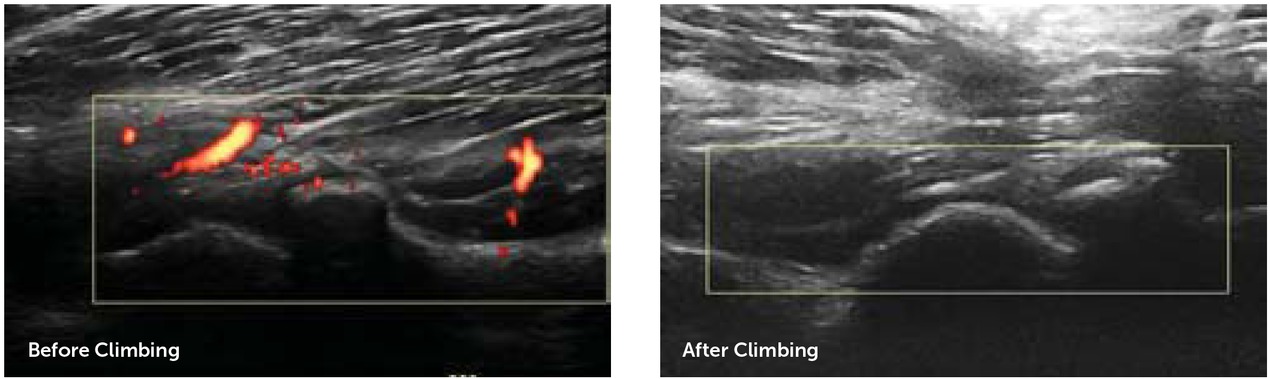

Fifteen arthropathic joints were identified in the UCSD cohort, of which 13 were further examined with MSKUS and PD pre-and post-climbing; two were dropped due to insufficient imaging. There was no change in cartilage and soft tissue thickness during the program. Supplemental Table 1 depicts cartilage and soft tissue measurements in detail. PD signals improved substantially in eight arthropathic joints, including four out of six arthropathic elbows and four out of five arthropathic ankles (Figure 2A). Overall, this resulted in a decrease of median PD score from 4 (range: 1 to 6) to 3 (range: 1 to 5), indicating a meaningful decrease in inflammation and vascular remodelling. Figure 2B shows a comparison of MSKUS of the long axis of a humeroradial joint before and after the climbing program indicating an improvement in PD scores from 2/3 to 0/3.

Figure 2A

Power doppler signal pre- and post-climbing program. Power doppler (PD) signal was assessed with MSKUS before and after completion of the climbing program. Three representative views in each joint were combined for PD scoring (0 indicates absent signal; 9 represents highest signal intensity). The line graph represents the PD signal score before and after climbing for each joint

Figure 2B

Representative example of soft tissue inflammation before and after the climbing program assessed by power doppler, detecting abnormal vascularity as marker of inflammation. A substantial reduction of inflammation post-climbing is depicted in longitudinal axis of the elbow humero-radial joint

Discussion

“Haemophilia Vertical”, an individualised climbing program for PWH, has recently been shown to improve joint and health-related parameters in a number of young PWH [19,20]. Based on increasing patient demand to engage in a climbing program, regardless of the severity of their arthropathies, we considered it important to also evaluate climbing therapy in older patients with more advanced arthropathies.

Here, we demonstrated that Haemophilia Vertical had positive effects in patients with arthropathies. All patients enhanced their climbing skills, and four out of six patients experienced clinical improvements in the HJHS. In addition, joint evaluation with MSKUS/PD demonstrated a decrease in inflammatory vascular signal in most arthropathic joints, and no detrimental changes in soft tissue and osteochondral tissue thickness. Moreover, top rope climbing on usual clotting factor prophylaxis, within 24 hours of factor dosing, did not elicit excess joint bleeding; ABR and clotting factor consumption remained stable. Interestingly, while patients expressed a general improvement in wellbeing and new confidence to overcome challenges, there was no measurable positive effect on QoL. This may have been because QoL scores were already very high at the outset of the climbing program, with little room to improve beyond baseline.

Several classifications of sports risks have been developed based on the expected frequency and severity of collisions [1]. The primary risk when climbing is falling, which would be especially detrimental for PWH. Top rope climbing has to be distinguished from other forms of climbing – such as bouldering or free climbing in a natural setting – that may carry a higher risk of injury and, in haemophilia, potentially a higher risk of bleeding. It is therefore understandable that the taxonomy compiled by the NHF has generally characterised climbing as moderate bleeding risk, possibly discouraging patients from taking up top rope climbing. With top rope climbing, however, the climber is secured by the belayer using an anchored rope and will fall only a short distance. Furthermore, ropes are designed to stretch to effectively cushion falls. In this context it has been shown by sports medicine experts that the injury risk of top rope climbing is low [30], and may therefore not be as dangerous for PWH as free climbing. Although our study is a case series and not powered to assess general safety of top rope climbing, the absence of increased bleeding rates during the climbing program provides no immediate alarming evidence of safety concerns.

Although not formally assessed, psychological benefits were observed in many patients as the curriculum progressed; for example, better communication skills in terms of evading isolation, befriending peers, and more ambitious personal goal-setting. Since these benefits became apparent during the program, without any planned prospective measures in place to capture such psychological or emotional changes, we conducted informal interviews at the end of the climbing program. Results from these interviews and from conversations with patients further supported meaningful gains in self-confidence and overall happiness with their physical achievements to an extent that we had not experienced previously with other patient activities.

Each climber was able to select a climbing route best suited to his own skills, which allowed patients with diverse physical abilities to train together in one group. This resulted in a spirit of camaraderie and encouragement where each patient was motivated not only by his own accomplishments, but also by the successes of his peers.

Top rope climbing is a team sport that requires a belayer to secure and take responsibility for the climber and participants must alternate between climber and belayer roles continuously. The belayer must anticipate and adjust for the climber’s movements while maintaining communication. Moreover, climbing challenges patients to exceed their personal limits by mastering increasingly difficult moves and overcoming weaknesses in terms of body position, grip, balance and mental control. Mastering this complex combination of physical and mental skills made climbing an exceptional experience for PWH, who often feel limited by their physical ailments. Patients improved their climbing skills despite severe physical limitations, suggesting that top rope climbing may be an ideal sport that positively influences self-esteem and personal achievement.

In particular, ankle function can be intensively trained during climbing. While clear data are lacking, there is an increasing perception among haemophilia care providers that ankle mobility deteriorates more rapidly than elbow or knee mobility. Lack of ankle mobility becomes pertinent during activities of daily living, especially walking [31,32]. Thus, one may speculate that top rope climbing will benefit ankle mobility and strengthening, and additional studies with more patients would show such benefits formally.

Importantly, measurements of MSKUS images showed no negative effects of climbing therapy on joint cartilage or soft tissue. Additionally, a decrease in vascular abnormalities visualised by PD signalling was identified in eight arthropathic joints. This is important as joint vascular abnormalities are not only a hallmark of inflammation, but have also been associated with a higher risk of joint bleeding and progressive arthropathy [29,33]. Consequently, a decline in vascular abnormalities in intra-articular joint tissue should further contribute to improved joint health.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the small sample size reduces the generalisability of our observations, but it is difficult to proctor and supervise more than six to eight course participants per session. Also, the observation period of three months is relatively short, and does not permit the evaluation of long-term effects on overall joint health, especially since assessments were limited to ankles, knees and elbows. Additionally, while the HJHS is widely accepted as a joint assessment tool for all ages in the clinical setting, it has been validated for use in children only. There is emerging evidence of the applicability of HJHS to adults [34, 35, 36], but to what extent numerical improvements are clinically meaningful is not well defined (children and adults).

Despite these shortcomings we believe that our observations provide preliminary evidence to suggest that patients with arthropathic joints should not be discouraged from engaging in top rope climbing. Of particular value is the increasing popularity of this sport in general, thereby providing a platform for PWH – and perhaps young PWH in particular – to mix and mingle with their non-haemophilia contemporaries. Mixing with active young people may counteract the isolation or stigmatization that some PWH feel as a consequence of their physical limitations.

Conclusion

The observations from this pilot study demonstrate that top rope climbing can be administered with appropriate professional oversight as an innovative concept to promote better physical health among adult PWH with advanced arthropathies. Larger studies, also assessing joints not typically affected by haemophilic arthropathy, such as shoulders and wrists, are necessary to evaluate short- and long-term joint outcomes of Haemophilia Vertical top rope climbing therapy.